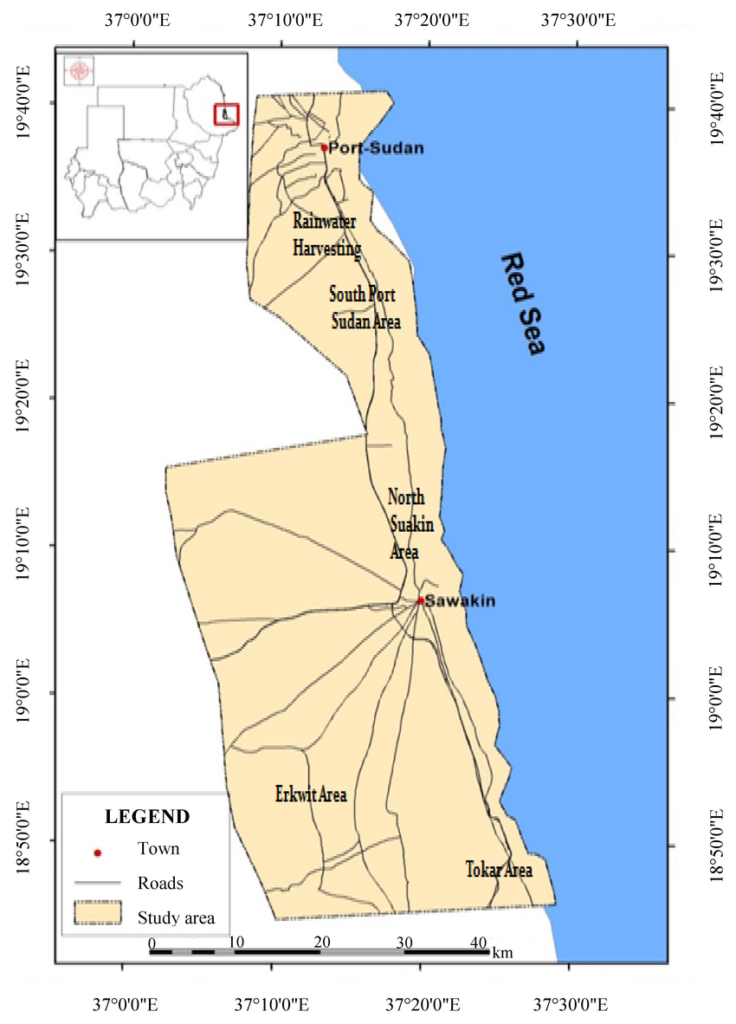

Russia’s negotiations with Sudan to establish a permanent naval facility in Port Sudan represent one of Moscow’s most consequential strategic moves outside the post-Soviet space. A Russian base on the Red Sea — one of the world’s most critical maritime chokepoints — would provide the Kremlin with unprecedented leverage over global trade routes, enhance its military reach into Africa and the Middle East, and complicate U.S. operations across the Red Sea–Suez–Eastern Mediterranean corridor.

If completed, the Sudan base will become Moscow’s primary warm-water access point to the Indian Ocean and a forward operating hub for intelligence, logistics, and maritime power projection. This development directly narrows U.S. room for maneuver in a region already stressed by instability, Iranian activities, and Great Power competition.

Russia’s Strategic Vision in the Red Sea Basin

Since 2017, Moscow has pursued the establishment of a naval logistics point in Sudan. The initial draft agreement granted Russia:

- a 25-year lease in Port Sudan,

- the right to station up to 300 Russian personnel,

- permission to host four naval vessels simultaneously, including nuclear-powered ships,

- free entry and exit for Russian military cargo.

This is not a “logistics hub” in the narrow sense — it is a forward naval base by another name.

Russia’s strategic objectives include:

- Securing access to the Red Sea and Indian Ocean.

- Challenging U.S. dominance near Suez.

- Developing military infrastructure in Africa to support Wagner/Rosatom/Russian diplomacy.

- Creating pressure points against Western maritime routes.

The Sudan base is a central component of Russia’s long-term plan to build a distributed military presence across Africa — from Libya to CAR, Mali, and the Red Sea.

Why the Red Sea Matters to Russia

Control of a global trade artery

12–15% of world trade passes through:

- the Bab el-Mandeb Strait,

- the Red Sea,

- the Suez Canal.

A Russian naval presence here gives Moscow:

- visibility over global shipping patterns,

- influence over chokepoints critical to Europe and Asia,

- leverage during geopolitical crises.

Opportunity to pressure U.S. naval operations

A base in Sudan allows Russia to:

- monitor U.S. Fifth and Sixth Fleet movements,

- track U.S. transit between the Mediterranean and Indo-Pacific,

- complicate American force flow in a crisis,

- challenge U.S. dominance of chokepoint waters.

2.3. Projection of power into Africa

The base provides operational support for:

- Wagner units in CAR, Mali, Sudan, Libya,

- Russian diplomatic missions,

- arms transfers,

- extraction of African resources.

It creates a secure maritime lifeline for Moscow’s Africa networks.

How the Sudan Base Narrows U.S. Operational Freedom

Intelligence and Surveillance Threats

From Port Sudan, Russia can deploy:

- signals intelligence equipment,

- electronic warfare units,

- maritime surveillance systems,

- underwater monitoring of shipping lanes.

This allows Russia to track:

- U.S. naval assets,

- NATO movements,

- commercial vessels,

- potential targets in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Port Sudan becomes a listening post aimed at the U.S. and allies.

Anti-Access / Area Denial (A2/AD) Potential

Once operational, Russia could gradually introduce:

- Kalibr cruise-missile capable ships,

- coastal defense systems (Bastion, Bal),

- surveillance drones,

- air defense assets (Pantsir, Tor, potentially S-300 variants).

This would establish a Russian A2/AD bubble near:

- the Suez Canal,

- Red Sea shipping lanes,

- U.S. naval transit routes.

Even a modest A2/AD footprint narrows U.S. flexibility in crisis scenarios.

Support for Russian and Iranian Maritime Operations

The Sudan base enables:

- coordination with Iran in the Red Sea,

- maritime logistics for Russian vessels coming from the Eastern Mediterranean,

- presence near Houthi-controlled Yemen,

- potential Russian–Iranian dual-use naval operations.

The U.S. currently counters Iranian-supported disruptions to shipping.

A Russian base adds a second hostile maritime actor to the environment.

Protection for Russia’s Shadow Fleet and Sanctions Evasion

A Red Sea hub facilitates:

- covert transport of gold, arms, and energy

- refueling and repairs for shadow tankers

- maritime transshipment outside Western oversight

- movement of sanctioned goods between Africa, the Middle East, and Russia

This erodes U.S. sanctions enforcement.

Why Sudan is Key to Russia’s Africa Strategy

Russia sees Sudan as:

A gateway to Africa

Positioned between the Sahel and the Horn, Sudan is ideal for:

- coordinating Wagner deployments,

- projecting influence into CAR, Mali, Ethiopia, Libya,

- supporting resource extraction operations.

An essential link to Russia’s gold operations

Russia-backed networks (Wagner, affiliated companies) extract gold in Sudan to fund operations and evade sanctions.

A naval base protects this revenue stream.

A strategic counterweight to Western and Gulf states

Port Sudan gives Russia a foothold across from:

- U.S. bases in Djibouti,

- French naval presence,

- Chinese PLA Navy base,

- Gulf monarchies’ Red Sea interests.

This creates a new tripolar dynamic: U.S.–China–Russia competition.

The U.S. Response: Strategic Dilemmas

Washington faces several challenges:

Limited influence over Sudan’s factions

Both SAF (Burhan) and RSF (Hemedti) have courted Russia.

The civil war gives Moscow leverage:

Russia supports whoever gives it the base.

The U.S. lacks a coherent Red Sea strategy

While the U.S. maintains a major presence in Djibouti, Washington has:

- no strategic anchor in Sudan,

- limited influence in Eritrea,

- minimal leverage in Ethiopia,

- fragmented diplomacy with Red Sea states.

Russia exploits this vacuum.

Balancing against China while countering Russia

The Red Sea hosts:

- China’s first overseas base,

- expanding Chinese maritime presence,

- Russian ambitions now emerging.

The U.S. must compete against two peer rivals simultaneously.

Future Scenarios

Scenario 1: Russia secures the base (high probability)

This becomes Moscow’s primary Indian Ocean hub.

U.S. operational freedom narrows significantly.

Scenario 2: Sudan collapses further; Russia plays both sides

Chaos benefits Russia — it can negotiate with winners or occupy territory informally.

Scenario 3: The U.S. and Gulf partners block the agreement

Possible only if coordinated pressure is applied to both SAF and RSF.

Scenario 4: China undermines Russia’s presence

Beijing may limit Russia’s activities if they interfere with China’s Djibouti operations or Belt and Road corridors.

A New Geostrategic Reality for the United States

A Russian naval base in Sudan would be the most significant geopolitical shift on the Red Sea in decades. It would:

- challenge U.S. dominance near the Suez Canal,

- strengthen Russia’s Africa posture,

- enable Moscow’s partnership with Iran,

- complicate U.S. Navy operations,

- undermine global maritime security,

- and support Russia’s sanctions evasion.

The Red Sea is no longer a peripheral theater:

it is an emerging frontline in U.S.–Russia strategic rivalry.

Washington’s ability to maintain freedom of maneuver near Suez increasingly depends on whether it can prevent Russia from establishing a permanent military footprint in Sudan.

Timeline of Russia’s Negotiations for a Naval Base in Sudan and the Problems Moscow Faced

2017–2018: Initial Overtures and Secret Negotiations

2017 (late)

- Russia begins exploring naval access on Sudan’s Red Sea coast.

- President Omar al-Bashir (facing sanctions and internal pressure) seeks Russian security guarantees and political support.

December 2017

- Al-Bashir meets Putin in Sochi and formally proposes hosting a Russian naval facility in Sudan.

- Russia sees Sudan as a foothold for expanding its Africa strategy and challenging U.S. naval dominance near Suez.

Problems for Russia:

- Al-Bashir is unstable and increasingly isolated internationally.

- Russia must negotiate amid Sudan’s economic collapse and political fragmentation.

2019: Regime Collapse and Strategic Uncertainty

April 2019

- Omar al-Bashir is overthrown in a military-civilian uprising.

- The transitional government suspends several controversial agreements, including military basing talks.

Problems for Russia:

- Loss of a reliable authoritarian partner.

- New transitional authorities are more cautious toward Russia.

- U.S. and Gulf states begin increasing diplomatic pressure to block Russian basing plans.

2020: Draft Agreement Reached — but Not Ratified

November 2020

Russia signs a preliminary agreement with Sudan allowing:

- a 25-year lease of a naval logistics point near Port Sudan,

- up to 300 Russian personnel,

- 4 Russian ships, including nuclear-powered vessels,

- rights to import weapons without Sudanese inspection.

This is the closest Moscow ever comes to finalizing the base.

Problems for Russia:

- The transitional government still refuses to ratify it in parliament.

- Sudan demands stronger political and economic concessions.

- Growing pressure from Washington and Gulf monarchies to derail the deal.

2021: Sudan Backtracks Under International Pressure

March 2021

- Sudan’s military council announces a “review” of the agreement.

- Sudanese generals complain Russia offered insufficient financial compensation.

June 2021

- Sudan officially suspends implementation of the agreement.

- Reports surface that Khartoum seeks a renegotiation with better terms.

Problems for Russia:

- Internal divisions in Sudan’s government (civilian vs military)

- U.S. re-engagement in Sudan under the Biden administration

- Gulf states’ concerns about Russian presence near their maritime routes

- Competition with Egypt, which wants Red Sea influence without Russia

2022: Russia Pushes Again as Sudan’s Politics Collapse

2022 (early)

- After Sudan’s military takeover, Russia renews pressure.

- General Burhan signals openness but hesitates to commit.

February 2022

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine complicates diplomacy.

- Sudanese elites fear being seen as enabling a sanctioned power.

2022 (throughout)

- Russia leverages Wagner Group networks in Sudan (especially gold smuggling operations) to influence decision-makers.

Problems for Russia:

- Sudan’s unstable political environment makes long-term commitments impossible.

- Armed Forces (SAF) vs Rapid Support Forces (RSF) rivalry deepens.

- Moscow is forced to negotiate simultaneously with both factions.

2023: Sudan Civil War — Russia Tries to Back Both Sides

April 2023

- Full-scale civil war erupts between SAF (Burhan) and RSF (Hemedti).

- Russia takes a pragmatic approach:

- Wagner supports RSF, offering weapons in exchange for gold export routes.

- Russian diplomats maintain relations with SAF to keep negotiations alive.

Problems for Russia:

- Russia must hedge between two hostile factions.

- The base agreement cannot be implemented during civil war.

- Western scrutiny increases dramatically after Wagner’s role becomes visible.

Late 2023

- Russia attempts to rebrand Wagner forces under the MoD,

trying to ensure continuity of influence even after Wagner’s leadership crisis.

2024–2025: New Russian Diplomacy — Closer to a Final Deal, but Hurdles Remain

2024

- The Kremlin pushes harder for a formal base agreement, presenting it as part of Russia’s “Red Sea Strategy.”

- Russian officials suggest major investments in Port Sudan in exchange for basing rights.

Key problem: Russia needs one stable Sudanese authority to sign the deal — but Sudan remains fragmented.

2025 (ongoing)

- SAF reportedly signals willingness to finalize the agreement if Russia provides:

- weapons,

- drones,

- training,

- political recognition.

- RSF also quietly offers Russia access in exchange for deeper Wagner-linked military cooperation.

Russia is attempting to play both sides until one emerges victorious.

Remaining Problems:

- Civil war prevents legal ratification

- U.S. actively warns Sudan against hosting Russia

- Gulf monarchies (Saudi Arabia, UAE) oppose a Russian foothold

- China is uncomfortable with a rival naval power near Djibouti

- Sudan’s internal factions fear empowering Russia too much

- Russian Navy is overstretched due to Ukraine war.

Summary of the Main Problems Moscow Faced

Political barriers

- Collapse of al-Bashir regime

- Rival governments (civilian vs military)

- Ongoing civil war (SAF vs RSF)

Geopolitical pressure

- U.S. diplomatic opposition

- Gulf states resisting Russian expansion

- China’s concerns about competing basing near Djibouti

- Egypt’s discomfort with Russia near Red Sea shipping lanes

Operational limitations

- Russian military overstretched in Ukraine

- Financial constraints due to sanctions

- Limited ability to protect the base during Sudan’s civil war

Local dynamics

- Competition with Wagner’s gold-smuggling interests

- Fear in Sudan that Russia could back one faction against another

- Demands for higher financial compensation

Why Russia Still Pursues the Base Despite All Obstacles

Despite setbacks, Moscow continues to push because:

- The base is Russia’s only path to a permanent Indian Ocean presence

- It strengthens Russia’s Africa strategy

- It challenges U.S. naval dominance near Suez

- It supports Russia–Iran cooperation in the Red Sea

- It provides strategic depth beyond Europe and the Black Sea

Russia views Port Sudan as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reshape maritime power balances — and it is willing to navigate all complexities to secure it.

The U.S. can still complicate or even block Russia’s Red Sea expansion, but it has to treat Port Sudan and the wider Red Sea as a serious strategic theatre—not a sideshow.

Make Sudan Too Costly and Unstable for a Russian Base

Work the factions: play spoiler on both SAF and RSF deals with Moscow

Right now Moscow’s strategy is simple:

“We don’t care who wins in Sudan, as long as someone gives us a base.”

The U.S. needs the opposite:

“Whoever thinks of giving Russia a base will pay a political and economic price.”

Tools:

- Private warnings to both SAF (Burhan) and RSF (Hemedti):

- A formal Russian base = obstacles to international recognition, IMF access, debt relief, investment.

- Tie any future normalization (lifting of sanctions, recognition, reconstruction aid) to a clear red line:

- No permanent Russian naval facility on the Red Sea.

- Use back channels via Egypt, Saudi Arabia, UAE to convey the same message to Sudan’s generals:

- If you invite Russia in, you lose us.

Result: Russia can negotiate, but every step toward a base increases the cost and diplomatic isolation of whoever signs.

Use Regional Powers to Box Russia Out

Mobilize Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and UAE against a Russian base

All three have strong reasons to be wary:

- Egypt doesn’t want a Russian naval outpost sitting on the same lane as Suez.

- Saudi and UAE want to dominate Red Sea security themselves and fear extra great-power competition.

Washington can:

- Back Egyptian & Gulf diplomatic pressure on Sudanese factions:

- “We will fund your reconstruction, but we will not share the Red Sea with a Russian fleet.”

- Help build a Red Sea security framework (Saudi-led or Egypt-Saudi-UAE) that explicitly excludes extra-regional bases—especially Russian.

If Sudan sees that all major Arab partners are against a Russian facility, it becomes politically toxic in Khartoum.

Offer Sudan an Alternative Security and Economic Deal

Right now Russia’s pitch is:

“We give you weapons, political cover, and a bit of money; you give us the coast.”

The U.S. doesn’t need to “out-bribe” Moscow, but it does need to offer a convincing alternative future.

3.1. Security cooperation without permanent U.S. basing

- Expand training, intel sharing, counterterrorism cooperation with Sudan if it commits not to host Russian naval forces.

- Offer limited rotational presence, joint exercises, and coast-guard support rather than permanent U.S. bases (which Sudanese elites might resist anyway).

3.2. Economic incentives

With partners (EU, Gulf, IFIs):

- Targeted reconstruction aid for Port Sudan and infrastructure on condition that no Russian base appears.

- Support for trade corridors, agriculture, and energy projects that reduce Sudan’s dependence on Russian money and Wagner’s gold networks.

Core idea:

Make it clear that either Sudan gets a Russian base and remains a pariah-war economy,

or it stays base-free and gets access to Western and Gulf reconstruction and investment.

Disrupt Russia’s Enablers: Wagner/“Africa Corps” and Gold

The base is not an isolated project. It is tied to:

- Russian mercenary structures (Wagner → Africa Corps)

- gold smuggling and sanctions evasion

- arms flows to Sudanese factions

Sanction the financial spine

- Hit gold companies, front firms, banks, and shipping channels tied to Russian operations in Sudan.

- Coordinate with EU and UK so that any vessel or company servicing Russian mining and logistics networks risks being cut out of Western markets.

4. Target key individuals

- Designate Sudanese elites facilitating Russian basing or gold operations.

- Make it personally risky for generals and businessmen to sign anything with Moscow.

If Russia’s Sudan network bleeds money and faces constant disruption, the base becomes more symbolic project than practical asset.

Turn the Red Sea into a “Managed Space” Unfriendly to New Russian Bases

Build a Red Sea Security Architecture that excludes Moscow

Work with:

- Saudi Arabia

- Egypt

- Jordan

- Djibouti

- possibly Ethiopia (carefully) and Kenya, plus France/Italy/Japan already in Djibouti

Goals:

- Joint Red Sea patrols and information sharing.

- Agreement on no new external bases without regional consultation.

- Maritime domain awareness network that tracks any suspicious Russian naval movement.

If the Red Sea becomes an organized security space, any Russian base looks like an alien, destabilizing outlier—easier to isolate diplomatically.

Embed the issue in NATO and EU debates

- Frame Russia’s Red Sea ambition as part of a broader anti-NATO maritime strategy (Black Sea → East Med → Red Sea).

- Use this to mobilize French, Italian, Greek, Spanish interest: all depend heavily on Suez.

That creates a coalition of maritime stakeholders who quietly or openly oppose Russia’s presence.

Use Information and Legal Tools to Delegitimize the Base

Expose what the base really is

- Publicly document how the facility supports:

- Wagner/Africa Corps deployments,

- gold smuggling,

- arms shipments to juntas and militias,

- sanctions evasion.

Turn the Russian base into a synonym for criminality and instability, not “balance” or “security.”

Promote legal challenges

- Support Sudanese civil actors and international NGOs in arguing that any basing agreement:

- violates Sudan’s constitutional frameworks,

- was signed by illegitimate authorities,

- undermines sovereignty.

The more legal controversy surrounds the deal, the more fragile it becomes—even if signed on paper.

Prepare Military and Operational Countermeasures (If the Base Happens Anyway)

Even if the U.S. cannot prevent the base, it can neutralize its utility.

Restrict what Russia can safely deploy

By:

- Signaling that deployment of long-range missiles or advanced air defenses in Sudan would trigger additional sanctions and possibly targeted naval/air counter-posturing.

- Making clear to Khartoum that allowing certain categories of Russian systems (e.g., Kalibr-capable ships, coastal missile batteries) will have direct consequences for Sudan’s relations with the U.S. and Gulf partners.

Enhance U.S. and allied presence around the Red Sea

- Strengthen Djibouti and other regional facilities.

- Increase maritime surveillance and P-8 patrols.

- Integrate allied navies into a persistent presence that makes it hard for Russia to operate unseen.

In other words: if the base exists, make it a glass house constantly watched and operationally constrained.

Coordinate Quietly with China Where Interests Overlap

China is not thrilled about:

- another great-power navy next to its base in Djibouti,

- Russian capacity to interfere in shipping,

- extra competition for influence in the Horn of Africa.

While Washington and Beijing are rivals, there is a narrow shared interest:

- Red Sea stability,

- uninterrupted trade,

- no unpredictable Russian A2/AD bubble.

The U.S. doesn’t need a formal agreement, but can:

- send private signals to Beijing that a larger Russian military footprint complicates both sides’ economic interests,

- quietly encourage China to lean on Sudanese authorities not to over-arm Russia in Port Sudan.

If both the U.S. and China quietly discourage an ambitious Russian build-up, the base is more likely to stay a small “logistics point” rather than a true power-projection hub.

To prevent or blunt Russia’s Red Sea expansion, the U.S. must:

- Raise the political and economic cost of any Russian base deal for Sudanese elites.

- Use regional partners (Egypt, Gulf states) as primary pressure vectors.

- Provide an alternative security and economic path for Sudan.

- Target Russia’s enabling networks (Wagner/Africa Corps, gold and arms channels).

- Shape Red Sea security architecture to make Russian basing politically unacceptable.

- Prepare military countermeasures to neutralize the base if it appears.

- Quietly leverage Chinese discomfort with Russian naval expansion.

If Washington treats Port Sudan as a central element of Russia’s long-term global strategy—rather than a local African issue—it can still prevent the base from becoming the “second Tartus” and keep U.S. operational freedom near Suez largely intact.

More on this story: The Sudanese army is at risks of collapse.

More on this story: Sudan’s struggle for power might weaken the position of the military