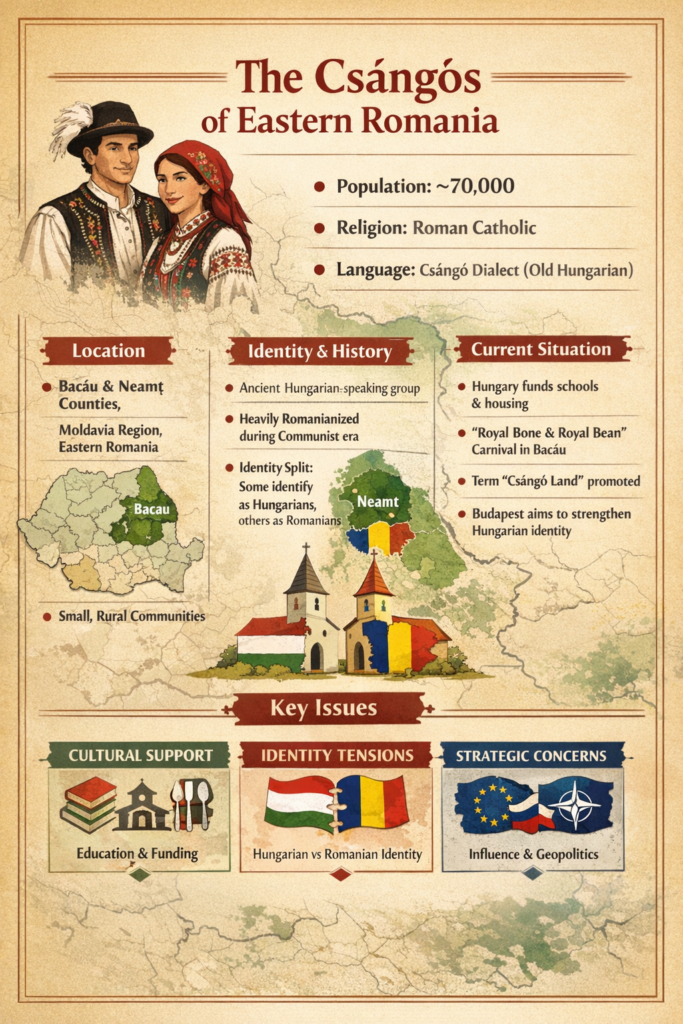

The Hungarian government is actively investing state funds in the development of the Csángó Hungarian ethnic group located in eastern Romania, within the Romanian region of Moldavia. Official Budapest supports the Csángó community not only through funding and investments, but also by participating in the organization of a local carnival called “The Royal Bone and the Royal Bean,” held in the city of Bacău. Budapest also finances housing construction, Hungarian-language education, and meals for children in 35 localities in the counties of Bacău and Neamț.

One of the key roles in strengthening Budapest’s influence over the Csángó community is played by Katalin Szili, former Speaker of the Hungarian Parliament and currently an adviser to Viktor Orbán on issues of cross-border autonomy. In particular, she publicly uses and actively promotes in the media the political-geographical term “Csángó Land,” modeled on the already established term “Székely Land” (approximately 670,000 Székelys live compactly in three administrative regions of Romania). Members of the Hungarian ethnic minority in Romania have awarded Katalin Szili the honorary title “Godmother of the Csángós.”

The Orbán government is seeking to expand its influence over Hungarians in Romania.

Media reported that the Hungarian government is actively investing state funds in the development of the Csángó Hungarian ethnic group located in eastern Romania, within the Romanian region of Moldavia. Official Budapest supports the Csángó community not only financially and through investments, but also by participating in the organization of the local carnival “The Royal Bone and the Royal Bean,” held in the city of Bacău. Budapest also finances housing construction, Hungarian-language education, and food provision for children in 35 localities in the counties of Bacău and Neamț.

One of the key roles in strengthening Budapest’s influence over the Csángó community is played by former Speaker of the Hungarian Parliament and current adviser to Viktor Orbán on cross-border autonomy, Katalin Szili. In particular, she publicly uses and actively promotes in the media the political-geographical term “Csángó Land,” similar to the already established term “Székely Land.” From members of the Hungarian ethnic minority in Romania, Katalin Szili has received the honorary title “Godmother of the Csángós.”

Budapest is attempting to expand the boundaries of the Hungarian minority in Romania and significantly increase its influence over Romanian citizens of Hungarian ethnic origin, as well as over the Romanian state as a whole.

Unlike the predominantly Orthodox Romanian population, members of the Csángó minority are Roman Catholics. During the communist period, this minority was subjected to intensive Romanianization, as a result of which many Csángós—unlike the Székelys—became strongly Romanianized. Today, up to 70,000 people speak the Csángó dialect. Some Csángós identify as Hungarians, while others identify as Romanians. The government of Viktor Orbán is actively working to ensure that all members of the Csángó minority identify themselves as Hungarians.

Some Romanian politicians of Hungarian ethnic origin emphasize that “Hungarians in the Transylvania region have learned a great deal from Hungarians in the Moldavia region, because it is precisely here that being Hungarian is the most difficult.”

Key theses:

- Budapest is attempting to expand the scope of the Hungarian minority in Romania and significantly increase its influence over Romanian citizens of Hungarian ethnic origin and over the Romanian state as a whole.

- Some Romanian politicians of Hungarian ethnic origin emphasize that “Hungarians in the Transylvania region have learned a great deal from Hungarians in the Moldavia region, because it is precisely here that being Hungarian is the most difficult.”

- Senior Hungarian politician and jurist; served as Speaker of Hungary’s National Assembly (2002–2009) and was an MP for two decades.

- Since 2015, she has served as a Prime Minister’s Commissioner for “cross-border autonomy” / minority-autonomy affairs, and later as a senior adviser in Orbán’s system (Hungarian media profiles describe this role and its evolution).

- In that capacity she is a high-profile operator of Hungary’s “nation policy” (support and political coordination with Hungarian communities outside Hungary), often speaking publicly on minority rights and autonomy frameworks.

Does Szili has had official, protocol-level contacts with Russian-linked figures as part of normal parliamentary diplomacy—e.g., she met Metropolitan Kirill (later Patriarch Kirill) during an official church delegation visit to Hungary while she was parliamentary speaker.

- Hungary’s broader minority-policy ecosystem has, at times, intersected with actors alleged to have built networks reaching “from Moscow to Riga” in campaigns connected to Hungarian minority causes—this is discussed by investigative outlet VSquare, but it is not specific proof of Szili’s own Russian ties.

Thus, Szili is best understood as a domestic political instrument of Orbán’s cross-border autonomy agenda. Russia may benefit from friction between Hungary and Romania/EU, but Szili ≠ evidence of Russian direction.

Consequences for Romania

1) Sovereignty and internal-cohesion pressure (medium–high)

Budapest-backed cultural and educational infrastructure can evolve into parallel influence channels—especially if framed with quasi-territorial branding (“Csángó Land” analogous to “Székely Land”). This risks:

- politicizing identity,

- elevating autonomy debates,

- increasing suspicion toward local Catholic/Hungarian communities.

Inter-ethnic polarization and securitization (medium)

If Romanian politics frames these programs as foreign interference, it can produce:

- stigmatization of Csángó communities,

- local backlash,

- and a security-driven response that worsens community relations.

Policy friction with Hungary inside the EU/NATO (high)

Romania may push for:

- stronger EU scrutiny of “kin-state” influence practices,

- tighter transparency requirements for foreign-funded cultural/education programs.

A relevant precedent: European institutions have long debated “kin-state” preferential policies and their cross-border effects (e.g., Council of Europe discussions on minority protection vs. sovereignty sensitivities).

Consequences for Hungary

Reputational and diplomatic costs (high)

Budapest risks being seen as pursuing soft irredentism or “managed identity expansion,” which can:

- damage bilateral relations with Romania,

- complicate Hungary’s standing in EU forums already strained by rule-of-law disputes.

EU legal/political blowback (medium–high)

If the program looks like political engineering rather than cultural support, it can trigger:

- calls for EU-level oversight,

- investigations into funding routes and conditionality,

- and additional isolation in intra-EU bargaining.

Hybrid exploitation risk (medium)

Even if Budapest is acting autonomously, widening minority-related friction creates an opportunity structure for external actors (including Russia) to amplify tensions through disinformation and “community protection” narratives—especially in a region historically sensitive to minority autonomy disputes. (This is “benefit-by-friction,” not proof of coordination.)

What would change the Russia assessment (indicators to watch)

Russia involvement becomes more plausible if investigators uncover:

- Financial trails from Russian-linked entities into NGOs/media tied to autonomy messaging

- Coordination patterns (shared organizers, intermediaries, synchronized narratives across countries)

- Operational overlap with known Russian influence nodes (same cut-outs, same propaganda distribution networks)

“Szili’s role is best characterized as a state-sponsored ‘nation policy’ instrument: institutionalizing Budapest’s influence among Hungarian communities abroad through cultural, educational, and symbolic-geographical framing. While Russia may benefit from the resulting intra-EU frictions, open sources do not provide evidence that Szili’s activities are Russian-directed; the risk lies in indirect exploitation of the tensions her agenda can generate.”

Explicit separatism among Csángós is unlikely in the near term.

The more realistic risk is identity engineering and autonomy-adjacent framing that could, over time, create political friction or be exploited by third actors.

Estimated probability (next 3–5 years):

- Open separatist movement backed by Budapest: Low (5–10%)

- Sustained identity consolidation + autonomy rhetoric without secession: Moderate (30–40%)

- No meaningful escalation beyond cultural policy: Moderate (50–60%)

Why full separatism is unlikely yet.

Csángó demographics and identity structure

- The Csángós are numerically smaller, geographically dispersed, and internally divided in identity (some identify as Hungarian, others as Romanian).

- Unlike the Székelys, there is no compact territorial core capable of sustaining a credible separatist platform.

Implication: Separatism lacks the social and territorial prerequisites.

2) Hungary’s cost–benefit calculus

Under Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s “nation policy” aims to:

- expand cultural and political influence,

- avoid direct treaty violations that would provoke EU/NATO backlash.

Open separatism in Romania would:

- trigger a major bilateral crisis,

- worsen Hungary’s already fragile standing in the EU,

- risk counter-measures against Hungarian minorities elsewhere.

Implication: Budapest gains more from influence without rupture.

EU and NATO constraints

Both Hungary and Romania are EU and NATO members. Any overt separatist push would:

- invite EU legal scrutiny,

- risk Article 7 escalation against Hungary,

- harden Romania’s security posture.

Orbán historically pushes to the edge, then stops short of red lines.

Where the real risk lies (and why it matters)

1) Identity consolidation as a political instrument

Budapest’s actions—funding education, media narratives, symbolic geography (“Csángó Land”)—point to:

- identity standardization (encouraging all Csángós to self-identify as Hungarian),

- political socialization around Budapest-aligned narratives.

This does not equal separatism, but it creates a constituency that could later be mobilized.

2) Autonomy rhetoric creep (without secession)

The Székely Land precedent shows the pattern:

- cultural protection →

- political-geographical naming →

- autonomy discourse →

- sustained diplomatic pressure (not independence)

Applied to the Csángós, this would look like:

- demands for language rights,

- education and church autonomy,

- local administrative concessions.

This is plausible—and disruptive—without crossing into secession.

3) Third-party exploitation risk (Russia)

Even if Hungary does not promote separatism, Russia could:

- amplify narratives of “minority repression,”

- frame Romania as intolerant,

- internationalize disputes inside EU forums.

This would be opportunistic exploitation, not Hungarian–Russian coordination—but the effect is similar: internal EU friction.

What would raise the risk (early-warning indicators)

Separatism risk rises materially if you see:

- Formal political organizations claiming to represent “Csángó Land”

- Autonomy language replacing cultural-rights language in Budapest-linked media

- Cross-border political coordination (not just cultural funding)

- Internationalization efforts (petitions to EU/CoE framed territorially)

- Security framing (claims of persecution requiring “protection”)

Absent these, separatism remains low probability.

Consequences if Hungary crossed the line (counterfactual)

For Romania

- Rapid securitization of minority policy

- Harder stance toward Hungarian NGOs and schools

- Increased ethnic polarization (net negative for Csángós)

For Hungary

- Severe diplomatic isolation inside the EU

- Loss of credibility on minority protection norms

- Heightened scrutiny of all cross-border programs

Net result: high costs, low strategic gain.

Bottom line

Hungary is not likely to promote Csángó separatism.

It is likely to continue identity consolidation and autonomy-adjacent influence, stopping short of secession.

The main danger is not Budapest declaring separatism—but creating conditions that others can later weaponize.

- build a scenario matrix (status quo / autonomy creep / escalation),

- compare Csángó vs Székely risk profiles, or

draft policy recommendations for Romania and the EU.

Csángó vs. Székely: Comparative Risk Profile

- Székely case: High autonomy pressure, low secession probability, persistent and institutionalized.

- Csángó case: Low autonomy/secession probability, but higher risk of identity manipulation and external exploitation over time.

In short: Székelys are a political-territorial issue; Csángós are an identity-engineering issue.

Demography and territorial cohesion

| Factor | Csángó (Moldavia, Romania) | Székely (Transylvania, Romania) |

| Population size | ~70,000 speakers; identity split | ~650–700,000 |

| Territorial concentration | Dispersed across villages | Compact, contiguous area |

| Internal identity cohesion | Low (Hungarian/Romanian split) | High (strong Székely identity) |

| Administrative coherence | None | De facto regional identity (“Székely Land”) |

Assessment

- Székelys meet the minimum sociological prerequisites for autonomy claims.

- Csángós do not—no compact territory, no unified identity.

Separatism feasibility:

- Csángó: Very low

- Székely: Low–moderate (autonomy), very low (secession)

Historical politicization and precedent

| Factor | Csángó | Székely |

| History of political mobilization | Minimal | Extensive (post-1989) |

| Autonomy movements | Absent | Persistent, organized |

| Internationalization | Very limited | Repeated (EU, CoE forums) |

| Symbolic geography | Emerging (“Csángó Land”) | Established (“Székely Land”) |

Assessment

- Székely autonomy discourse is normalized and routinized.

- Csángó politicization is new and externally driven.

Risk type

- Csángó: Latent / developmental

- Székely: Structural / entrenched

3) Role of Budapest (Hungary)

| Dimension | Csángó | Székely |

| Type of Hungarian involvement | Cultural, educational, identity framing | Political, diplomatic, symbolic |

| Strategic objective | Identity consolidation | Autonomy pressure |

| Red-line awareness | High (Budapest cautious) | Medium (more assertive rhetoric) |

| Cost tolerance | Low | Higher |

Hungary (Hungary) gains:

- from Csángós → influence without confrontation;

- from Székelys → leverage through sustained pressure.

Budapest is more likely to push limits in Székely Land than among Csángós.

Risk of separatism vs autonomy

| Risk type | Csángó | Székely |

| Cultural autonomy demands | Low–moderate | High |

| Administrative autonomy demands | Low | High |

| Separatist rhetoric | Very low | Low |

| De facto parallel governance | Very low | Low–moderate |

Key point:

Neither case is likely to produce secession, but Székely autonomy agitation is structurally persistent, while Csángó autonomy would need to be artificially created.

Vulnerability to third-party exploitation (Russia factor)

| Vector | Csángó | Székely |

| Narrative manipulability | High | Medium |

| “Minority repression” framing | Easy | Familiar, saturated |

| External amplification potential | High (low baseline) | Medium (well known issue) |

| Strategic value for Russia | Indirect | Moderate |

Russia (Russia) would:

- exploit Csángó identity tensions opportunistically (cheap destabilization),

- use Székely issues more selectively, as they are already heavily politicized.

Paradox:

Csángós are less separatist but more exploitable informationally.

Consequences for Romania

For Romania:

- Székely track:

- Long-term governance challenge

- Requires institutional, legal containment

- Csángó track:

- Risk of overreaction and securitization

- Danger of turning a cultural issue into a political one

Worst mistake for Romania: treating Csángós as a separatist threat.

That would create the problem that does not currently exist.

7) Comparative risk score (next 3–5 years)

| Scenario | Csángó | Székely |

| Cultural influence expansion | High | High |

| Autonomy agitation | Low (10–15%) | Medium (35–45%) |

| Separatist movement | Very low (≤5%) | Low (≤10%) |

| External hybrid exploitation | Medium (30–40%) | Medium (25–35%) |

- Székelys = autonomy risk with political depth

- Csángós = identity risk with geopolitical spillover potential

Hungary is unlikely to push Csángós toward separatism, but identity consolidation today can become political leverage tomorrow, especially if external actors amplify tensions.

How Hungary Could Leverage Csángós in the April Elections

Voter mobilization and symbolic politics

Hungary may seek to motivate a diaspora voting bloc by:

- amplifying cultural identity and Hungarian language rights messaging,

- developing narratives of protection and solidarity,

- using high-profile visits, events, and media targeting Csángó audiences.

Although Csángós are a relatively small minority (many speak Romanian or are Romanian-identified), emphasizing cultural ties could spur greater political activation and turnout among those who feel ethnically Hungarian or marginalized. This is similar to how political actors appeal to diaspora voters elsewhere by tying issues of identity and rights to electoral stakes.

Why it matters:

Even a small surge in politically mobilized Hungarian-identifying voters in Romania could influence local races or regional balance, especially in multi-ethnic constituencies.

Narrative framing to create leverage

Budapest could use Csángó issues to shape broader political narratives:

- argue that Hungarian-language education and services are suppressed in Romania,

- frame Romania’s legal or educational policies as discriminatory,

- present Hungarian support as a response to these conditions.

This reframing can be amplified in Hungarian domestic media ahead of elections to paint a picture of Budapest defending Hungarians beyond its borders — which may appeal to segments of voters who prioritize national identity and kin-state support.

This is part of a broader Hungarian influence strategy that often frames minority support in “national sovereignty” and cross-border protection terms.

Institutional and diplomatic signalling

Budapest may time diplomatic visits, public announcements, and cultural investments to maximize visibility during the Romanian electoral cycle:

- support for Csángó language schools,

- funding for community events,

- prominent coverage of Csángó issues in Hungarian media.

These actions can create political pressure, especially if Romanian candidates differ in their approaches. Some may position themselves as defenders of national unity (opposed to external influence), while others may adopt a more conciliatory approach toward minority rights.

Indirect influence through allied Romanian political actors

Rather than directly targeting Csángó voters, Budapest might influence Romanian electoral dynamics by:

- engaging with Hungarian minority parties or alliances (e.g., Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania — UDMR — which has historically been a significant political actor).

- providing political capital to sympathetic figures within Romania

- signaling that minority votes matter and can be mobilized strategically

For example, in Romania’s 2025 presidential runoff, support from Hungarian voters in Transylvania was factored into campaign strategies, showing how external references to minority communities can influence internal politics.

Information and narrative campaigns (media influence)

Beyond formal electoral mechanics, Budapest could amplify narratives using:

- Hungarian-language media in Romania’s Moldavia region,

- targeted social media campaigns,

- amplified mentions of Csángó culture and “protection” rhetoric.

Such media can shape perceptions, create polarized discourse, and signal that Hungary “has Hungary’s back,” even if this does not directly translate into votes at scale.

Likelihood and Limits of This Strategy

Probability of meaningful electoral effect

- Low to moderate: Because Csángós are relatively small in number and not politically cohesive, any direct electoral impact is constrained.

- Moderate for symbolic influence: Messaging around ethnic solidarity may have a greater impact on domestic Hungarian voters in Hungary than on the Romanian electoral outcome itself.

Structural constraints

- Many Csángós are assimilated or fluent in Romanian and may not identify primarily as Hungarian.

- Romania’s constitutional framework limits foreign political interference — overt electoral campaigning by a foreign state would be controversial and could provoke backlash.

Strategic calculus for Budapest

Budapest is more likely to emphasize cultural support and identity narratives than explicit political mobilization. This reduces direct risk of diplomatic incident while still strengthening Hungary’s image among nationalist and diaspora-oriented constituencies in Hungary — which can benefit ruling parties domesticallyduring elections.

Possible Mechanisms for Exploitation

| Mechanism | Description | Likelihood | Political Effect |

| Identity mobilization | Cultural/identity appeals to Csángós | Moderate | Small electoral effect, larger symbolic leverage |

| Narrative framing domestically | Using Csángó issues in Hungarian campaigns | High | Boosts domestic nationalist support |

| Diplomatic signaling | Visits/aid timed with elections | Moderate | Political signaling, reputation effects |

| Support for Romanian minority actors | Indirect influence via aligned parties | Low–Moderate | Local influence within Romania |

| Media & info ops | Amplified identity messaging | Moderate | Narrative shaping, perception effects |

Hungary can exploit Csángó issues in the April elections most effectively through narrative and symbolic signaling that resonates with domestic audiences in Hungary and potentially with Hungarian minorities abroad.

Direct political influence on Romanian voters via Csángós is limited by demographic and identity fragmentation, but it can contribute to broader political narratives and strategic leverage.

If you want, I can turn this into a brief policy note with counter-measures Romania could adopt to de-politicize Csángó identity issues during the election cycle.

Here’s a clear, analytical assessment of how Budapest could exploit the Csángó minority in relation to the April elections, focusing on political mechanisms, incentives, and likely effects — grounded in what we know about the community and minority politics in Romania.

🇭🇺 How Hungary Could Leverage the Csángó Community in the April Elections

1) Identity Mobilization and Symbolic Appeals

Budapest can use cultural and identity narratives to rally support among:

- Csángós who self-identify as Hungarian,

- Hungarian-speaking or Catholic communities in Moldavia,

- Hungarian audiences domestically who view cross-border ethnic ties as politically salient.

By boosting Hungarian-language education, funding cultural events, and promoting the idea of a distinct “Csángó Land,” Hungarian authorities can frame the Csángó issue as a symbol of ethnic solidarity and transnational protection. Such narratives can then be amplified in Hungarian domestic political discourse to appeal to nationalist and diaspora-oriented voters.

Why it matters:

Even if the absolute number of Csángó voters is small, elevating their cultural distinctiveness feeds into broader identity politics that can influence opiniooters in Hungary and Hungarian minorities across the region.

Cultural Support as Political Signaling

Hungary’s investments — in Hungarian-language schooling, meals for children, housing, and local cultural events — create a material link between Budapest and Csángó communities. This can be used to:

- signal that Hungary “protects its own outside its borders,”

- underscore narratives of minority rights and cross-border solidarity,

- contrast Hungarian support with perceived neglect from Bucharest.

This kind of support does not directly translate into electoral votes in Romania, but it can be powerful political signaling in Hungarian elections, particularly if framed as Hungary standing up for minorities abroandirect Influence through Minority Political Actors**

While the Csángós themselves are less politically organized than larger Hungarian minority groups like the Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR), Budapest could still seek to align sympathetic political actors or civil organizations to advocate for policies that resonate with Hungarian voters during the election cycle, such as:

- enhanced minority education rights,

- cross-border cultural cooperation,

- recognition of Csángó cultural distinctiveness.

These aligned voices can be amplified in campaign messaging domestically.

4) Narrative Framing and Media Influence

Budapest can deploy targeted media narratives — in both Hungarian and international media — to highlight:

- perceived discrimination or lack of support for Csángó identity in Romania,

- Hungary’s proactive role in cultural protection,

- broader themes of cross-border ethnic brotherhood.

This can be reis in Hungarian press about Csángó support,

- social media campaigns,

- official statements linked to election timing.

Such framing can shape public perception well beyond the size of the Csángó population itself, turning a relatively small issue into a larger theme of national pride and cultural responsibility.

Why This Matters in the Election Contexts domestic politics

- Csángó issues can be used to mobilize nationalist or conservative voters ahead of April elections.

- Territorial and cultural symbolism resonates with Orbán’s broader strategy of exporting identity politics and defending “Hungarians everywhere.”

For Hungarian minorities in the region

- At the margin, some Hungarian minority groups may feel empowered or validated, potentially increasing turnout among those who feel culturally connected to Budapest’s initiatives.

For Romania

- Such external emphasis on Csángó identity risks being framed domestically as foreign influence in internal affairs, possibly mobilizing **Romanian nationalist senrceived external meddling.

Likelihood and Limitations

Probability of significant direct electoral impact in Romania:

Low to moderate — Csángós are a small and identity-diverse group; they are not a cohesive political bloc with high mobilization capacity.

Probability of influencing politics:

🔹 Moderate to high — identity and diaspora themes are politically effective symbols in Hungarian elections, particularly under the current government’s narrative style.

Budapest can exploit Csángó issues during the April elections primarily through narrative and symbolic influence, rather than direct political engineering among Romanian voters. The tactics would revolve around:

- Cultural and identity appeals,

- Signaling protective leadership over minorities,

- Using media to amplify cross-border solidarity narratives.

While such a strategy may not yield significant electoral returns in Romania itself, it can strengthen domestic political positioning for Hungarian political actors by appealing to nationalist and diaspora-oriented constituencies.

More on this story: Romania at risk after the Senate decides on the Szekely Land autonomy