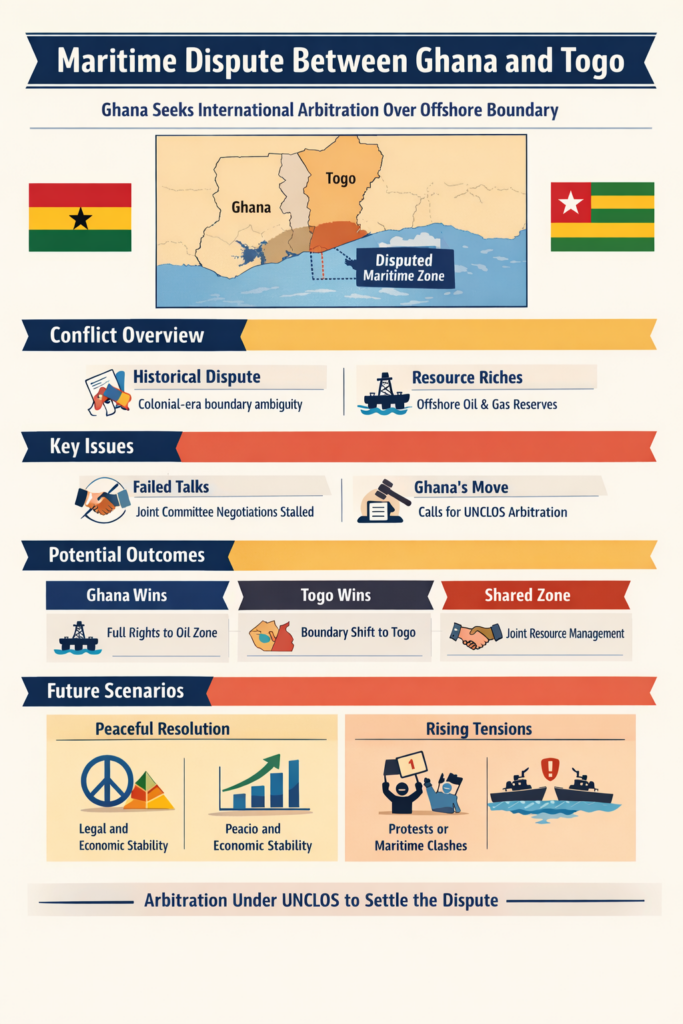

Ghana has formally notified Togo that it will pursue international arbitration under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to resolve a longstanding dispute over their maritime boundary in the Gulf of Guinea. This move reflects deep-rooted historical disagreements, competing economic interests linked to offshore oil and gas rights, and frustration with failed bilateral negotiations. By choosing a legal pathway, Accra aims to reduce tensions while preserving peace, but underlying strategic interests still carry the risk of future conflict if the arbitration outcome is contested.

Historical Background and Causes of the Dispute

Colonial Legacy and Ambiguous Borders

Like many African maritime disputes, the Ghana–Togo conflict has roots in colonial-era frontier demarcations. Boundaries drawn by colonial powers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries often lacked precise geographical coordinates, especially offshore. This ambiguity became more consequential as offshore energy resources gained economic importance.

- The dispute centers on how to delimit a maritime boundary that defines sovereign rights over offshore oil, gas, and potentially mineral deposits in the Gulf of Guinea.

Trigger Points

The most salient flashpoint occurred in 2017–2018, when Togolese authorities prevented Ghanaian seismic survey vessels from conducting oil and gas exploration in waters Accra considered its own. Ghana viewed this as an infringement on its sovereign rights, while Togo asserted competing claims over the same maritime area.

Following the 2017 incident, the two countries formed a Joint Maritime Boundary Technical Committee tasked with developing a mutually acceptable delimitation. However, persistent differences in methodological approaches, baseline coordinates, and nautical chart interpretations prevented agreement. Efforts at joint patrols, fishing coordination, and non-invasive exploration were negotiated, but these interim measures did not resolve the core boundary question.

Strategic Stakes and Underlying Drivers

Economic Interests: Oil and Gas Prospects

The disputed area lies offshore in a region with significant hydrocarbon potential. For Ghana, energy exports have been central to economic growth; securing maritime rights expands access to exploration and production. For Togo, securing equivalent rights is crucial for diversifying its economy and capturing revenue from offshore energy. These competing economic imperatives heighten the stakes of any boundary resolution.

Institutional Limitations

Both Ghana and Togo have strong incentives to maintain peaceful bilateral relations, but domestic political considerations complicate compromise. National pride and political constituencies tied to oil sector expansion make territorial concessions politically sensitive.

Why Arbitration? Possibility of Escalation

Shift to Legal Resolution

By invoking international arbitration under UNCLOS, Ghana is signaling both frustration with bilateral talks and a preference for rules-based settlement. This move may reduce immediate tensions by placing the dispute in a neutral legal forum rather than a political or military arena.

Risk of Non-Compliance or Contestation

Arbitration results under UNCLOS are legally binding; however, there is no supranational enforcement mechanismother than diplomatic and reputational pressures. If Togo perceives the outcome as unfavorable, Accra’s reliance on legal authority may still be challenged politically—especially if resource revenues are at stake.

Low Likelihood of Military Escalation—But Not Zero

Historical patterns in the Gulf of Guinea show that maritime disputes between neighbors rarely escalate into armed conflict, largely because of regional institutions (like the African Union) and shared economic interests in cooperative security. However, localized incidents—such as naval confrontations or fishing vessel detentions—remain possible if either side interprets enforcement actions as provocative.

Consequences of Arbitration and Possible Outcomes

Scenario A: Arbitration Decides in Ghana’s Favor

- Clear boundary line defined according to UNCLOS principles.

- Ghana gains exclusive rights to the contested offshore area.

- Increased investor confidence leads to accelerated oil and gas development.

- Togo may attempt to negotiate side agreements for revenue sharing or joint concessions to maintain stability.

Implications:

Economic benefits for Accra are substantial. However, domestic political pressure in Lomé may rise if Togo perceives limited access to resources.

Scenario B: Arbitration Favors Togo or Splits the Difference

- The decision might allocate portions of the contested area to both states.

- Togo could claim validation of its sovereign claims.

- Ghana may push for shared resource exploitation frameworks.

Implications:

This could ease bilateral tensions if framed as fair, but risk domestic backlash in Accra if perceived as a loss. Cooperative frameworks for exploration and production could emerge.

Scenario C: Arbitration Decision Is Contested or Rejected

- Togo might question the legal basis or fairness of proceedings.

- Bilateral tensions could rise again.

- Threat of localized maritime incidents increases.

Implications:

Renewed diplomatic tensions could undermine regional cooperation and investor confidence. Third-party mediation by the African Union or United Nations may be required.

5. Broader Regional Context

African states increasingly face maritime boundary and resource disputes across the continent, particularly in the oil- and gas-rich Gulf of Guinea. Regional institutions such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the African Union (AU) have frameworks for peaceful dispute resolution, but practical implementation varies by case.

Policy Implications and Recommendations

- Strengthen UNCLOS Implementation: Encourage both states to commit in advance to abiding by arbitration results.

- Establish Joint Resource Management Zones: Even if boundaries are agreed, mechanisms for shared exploitation can reduce competition and enhance cooperation.

- Regional Mediation Support: AU and ECOWAS should offer facilitation services to ensure arbitration does not reignite tensions.

- Transparency Measures: Regular public communication on proceedings can manage domestic expectations and reduce nationalist rhetoric.

The maritime dispute between Ghana and Togo reflects historic boundary ambiguities, economic competition for offshore resources, and frustrated bilateral diplomacy. Ghana’s decision to seek international arbitration under UNCLOS is a strategic attempt to resolve the dispute within a rules-based framework, lowering the risk of escalation. While military conflict remains unlikely, diplomatic, economic, and political tensions persist, and outcomes depend heavily on the arbitration ruling and its acceptance by both parties. The situation underscores broader challenges in African maritime boundary governance and the need for robust regional mechanisms for peaceful dispute resolution.