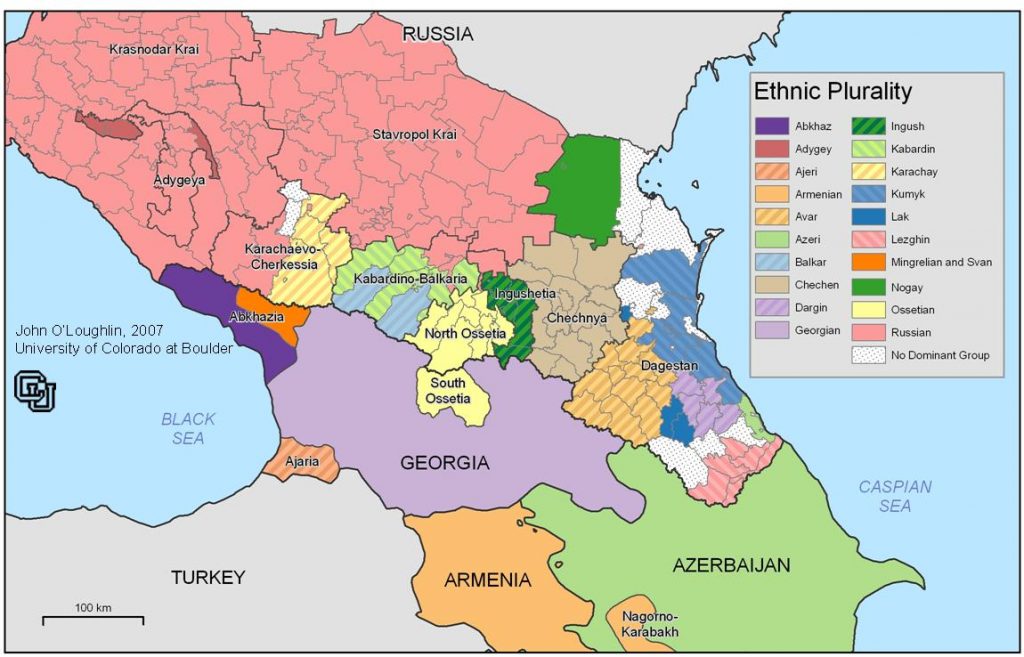

Russians are widely perceived as an alien ethnos in the North Caucasus, with religion multiplying the differences. The most significant separatist sentiments are usually expanded in Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia, while the least in North Ossetia.

Separatism is more or less specific to practically all Russian republics of the North Caucasus, but it is not always socially or economically grounded and might not drive this or that separatist project to success.

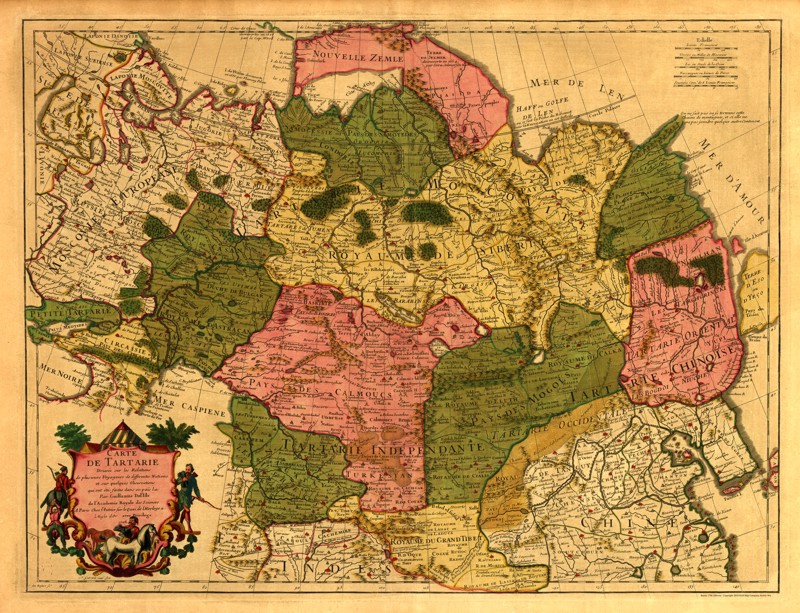

Separatism in the Caucasus is the strongest and most developed movement among all Russia’s parts. This owes to the history, a sharp demographic growth, and specific culture where the warrior cult and strength dominate. Russia, at different times, pursued an aggressive policy towards the Caucasian peoples, relying on forceful presence and waging long wars.

There are three main types of Caucasian separatist movements.

First, there is national separatism. It relates to Chechnya, mainly, but less to Ingushetia. Some researchers classify Chechnya as “failed states”. Both subordinate entities of the RF are actually mono-ethnic, show high birth rate and titular nation share gain, as well as rundown of ethnic Russians within their territory. The local elites, meanwhile, are pursuing a policy to strengthen the national identity of the population in every way possible. Sometimes, as in the case of Chechnya, the ideas planted are not just of identity, but of the nation’s supremacy.

National separatism is hardly economically or socially grounded everywhere. The national separatist project – Great Circassia is an example, targeting to unite lands once inhabited mainly by Circassians (Adygea, as well as most of Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia, Krasnodar and Stavropol Territories), the followers believe. These ideas are fairly common for the information space, but they have lukewarm support, not least over the scarce concentration of Circassians in this territory.

Second, there is religious separatism. Islam unites all Caucasian republics in the Russian Federation. Its weight is growing more and more. Moreover, Islam is developing among all age-groups and social categories. Religious separatism plays a central topic throughout the Russian Caucasus and is widely supported. This refers mainly to the establishment of the so-called Caucasus Emirate. It was proclaimed by now killed Dokka Umarov. Those who were for the establishment of this multiethnic Islamic state announced the following state and territorial division: Dagestan, Nokhchicho (Ichkeria), Galgaycho (Ingushetia), Iriston (North Ossetia), Nogai steppe (Stavropol Territory) and the united Vilayat of Kabarda, Balkaria and Karachay. Vilayat Iriston was abolished in 2009 and subsumed into Vilayat Galgaycho. Following Dokka Umarov’s death, the idea of establishing the Caucasus Emirate is widely supported but needs a new leader. If established, this state will have access to the Caspian Sea, transit potential, opportunities in energy and extractive sector, primarily the carbon one. Religious separatism is the most ubiquitous in Dagestan, where lots of different ethnic groups, predominantly Muslims, live. The remarkable thing is that the emirs of the Caucasus Emirate, Abu Dudzhan Gimrinsky, Abu-Usman Gimrinsky, and Ali Abu-Muhammad, were the natives of Dagestan.

Third, there is social and cultural separatism. Lots of people living in the Caucasus identify themselves as “Cossacks”. Cossacks are not an ethnic group, but their different groups feature their own cultures and behavior patterns. The need to shield from the radical Islamic population is the main reason for them to build up in social movements. Meanwhile, not all representatives of the Cossack movements are Russia-friendly. Islamization threat and the need to protect the Slavic population, amid steering away from the conflicts of the federal center, can serve as a boon for the separatist Cossack movement to boost, primarily in the Krasnodar Territory, where there is a historical tradition.

Russia’s strategy and tactics in countering separatism in the Caucasus is the following.

First, – to bribe the elites. Nearly half of the budgets in the North Caucasus republics are subsidies from the federal center. The budget subsidies from Russia accounted for 52% of Dagestan’s consolidated budget revenues in 2019, in Chechnya – 50%, in Ingushetia – 49%. And most of the funds go to local elites usually represented by one or more clans. The federal center concurrently “turns a blind eye” on corruption and the “informal tax” that business pays directly to representatives of the teips who control the republic. Immigrants from the North Caucasus, simultaneously, are allowed to work in the shadow niches of illegal business in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other large Russian cities, usually orchestrated by security chiefs. We are particularly talking about money laundering. Conflicts between security chiefs and the pro-government teips of the North Caucasus are common, therefore. The Kremlin is paying the price for regional comfort, however. Note that the appetites of the North Caucasus republics are growing year by year.

Second, – to eliminate the leaders and intimidate the opposition clans. Federal forces and local paramilitary groups make strides toward eliminating separatists and unprecedentedly harassing their relatives. This is remarkably gainless for local elites and lucrative for the federal government. Blood feud is still widespread in the Caucasus. If the dominant teip loses its strength and influence, for some reason, civil bloodshed is likely to come in Chechnya and Ingushetia, triggering decline for the whole territory.

Third, – to divide national and religious separatism. The Kremlin has succeeded in dividing these two trends. Moscow has ended the policy of chauvinism and ethnic discrimination it has pursued in the Caucasus for many years. It concurrently made a bid on strong national leaders in Chechnya and Ingushetia. In fact, both Chechnya and, to a lesser extent, Ingushetia informally have special status in the modern RF. And local leaders, at the same time, scrabble to eliminate conditions when religious separatism might unite with national ideology. Dagestan is a real exception in this context, having no titular ethnic group and, therefore, deprived of national separatism by definition. Here, separatism is at the highest level and has religious connotation.

Fourth, – backing the threat of interethnic conflicts in the Russian Caucasus. Numerous territorial disputes between Chechnya and Ingushetia, North Ossetia and Ingushetia, Chechnya and Dagestan, Adygea and the Krasnodar Territory play into the hands of the federal government, as they keep a single unifying religious separatist movement off balance.

Fifth, – to “dispose of” radical youth in armed conflicts outside the Russian Federation. Lots of radicals from the North Caucasus are mercenaries, including on the side of the IS and the Al-Nusra Front in the Syrian war. Though they receive combat experience they could theoretically apply at home, their number is reduced over the losses. Moreover, they spend a lot of time outside Russia and do not campaign within its territory. Russia’s special agencies, reportedly, are involved in recruiting radically minded youth in the North Caucasus into the above-mentioned organizations and facilitate their movement outside the RF.

Separatism in the North Caucasus will just gain strength in future, with the highest level observed in Dagestan. The contributing factors are:

– rapid demographic increase in the republics, further outflow of ethnic Russians, little if any integration by youth in Russia-wide cultural and linguistic space;

– high unemployment rate and low security growth for most households;

– stake by federal center on local teips and the “cult of power” and the otherness of local ethnic groups created by local elites, ultimately leading to the explosion of public anger;

– local elites lack a long-term vision of the development paths for the republics. They just work to keep the situation under control today;

– federal center lacks a long-term vision of economic development pattern for the republics;

– growing assertiveness among local elites for support from the federal center;

– intensifying religious factor among the youth and proactive efforts by informal ambassadors from Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey in the region.