The economic case study in the countries of South America and its charting on the map of protests in the countries of the continent, enables to trace the difference between the events in Chile and the protests in other countries.

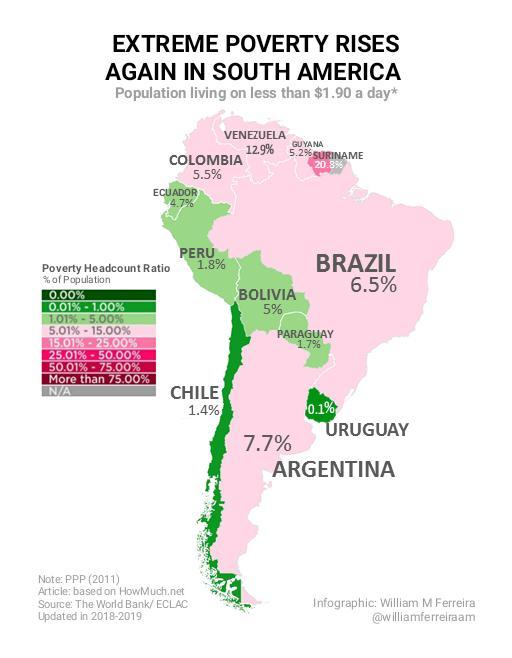

Social protests take place in the states where the share of population with a standard of living below $ 1.9 per day is more than 5%. The protests in Venezuela, where this figure is 12.9%, look quite logical. Bolivia, although it is trending – 5% – has more likely political reasons for the protests. However, the situation in Chile is very different from the big picture. The population below the poverty line is only 1.4%. This is an extremely low level of poverty, lower only in Uruguay.

Chile has overcome extreme poverty. In the country, the middle class layer as a percentage of the total population is the largest in the region. The country has full employment and foreign investment, and the noticeable development of the entrepreneurial class and specialists has led to a rapid increase in living standards.

The high cost of living amid low wages explains the situation.

Half of Chileans earn below just 400,000 pesos per month (equivalent to $500), and the distribution of household income in Chile shows that just the top 20 percent earn more than they spend each month on food, transport, housing, and basic services.

Under such conditions, the middle class suffers the greatest losses. Levels of household debt are high by regional standards and many Chileans have moved into less secure self-employment.

Thus, that was not the standard of living itself that triggered the escalation, but the rise in inequality that occurred due to risen subway prices amid gas prices hike and currency devaluation. Chile is the regional leader in household debt. The low level of Chileans’ fundamental social rights, the lack of guarantees for education and residence, have additionally fueled the protests.

The middle class is the first to respond to the economic crisis, because it is the most vulnerable economically. The developments in Chile, similar to the protests in France, may be the first to indicate the general crisis in global economy, the decline in the effectiveness of existing economic models, as well as a critical level of the material gap between rich and poor. Widening of this gap leads to the reduction in middle class, which acts as a driver for protest moods. Chilean protests demonstrate new economy and security challenge: the people’s need to implement the category of justice in the modern economic model. The danger is that this category is extremely close to left-wing ideological models, not a priori related to economic efficiency. Such people’s expectations may lead to an electoral shift to the left.

The moderate left has been paralyzed in the midst of this whole situation.

The far-left The Broad Front and other far-left legislators have presented a formal petition to remove Piñera on grounds he’s responsible for human rights violations that occurred in response to the protests. But there is little unity on the left around the effort. Javiera Parada, a well-known left activist, even broke from Jackson’s Democratic Revolution party in opposition to the move. According to the Cadem poll, around half of Chileans (49%) disapproved of Piñera’s use of the army to control protesters. But nearly the same amount (45%) say they agreed with his decision, and nearly 90% disagreed with the violence and destruction of public property that some of the protesters carried out.

Thus, a split of leftist forces over Piñera’s resignation enables Chilean leadership to embark on a process of constitutional change, supported by 80% of the population. Thus, Piñera can get the necessary time to stabilize the situation. In 2020, the elections of Regional Governors and Mayors and Councilorsare due to be held in the country, and in 2021, – elections of the President and half of the Senate.

As a result, the turn of Chile to the left may not occur.