El Salvador’s president’s endeavor to reduce a crime in the country amid downfall of relations with the parliament markedly affected by cartels and criminal organizations, spur him on to the actions likely to raise doubts about their legitimacy.

Armed soldiers and police officers accompanied El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele as he stormed the nation’s parliament on Sunday, February 9.

The president demanded that opposition lawmakers vote to approve his Territorial Control Plan to secure a $109 million loan that he says would be used to better equip military personnel and law enforcement officers in their job of tackling out-of-control gang violence in the country. The funds would buy a helicopter, police cars, uniforms, night-vision goggles and other equipment, including a video surveillance system. Bukele previously announced an initiative to recruit 3,000 new soldiers to combat gangs and criminal activity in the country. He has brought in 30 percent of that goal to date. He also made clear that he intends to implement a hard-hand approach to combating gangs, which satisfied many Salvadorians who overwhelmingly oppose negotiating with gangs.

After storming the parliament, Bukele said a prayer from a seat normally occupied by the president of the parliament, Mario Ponce. Before leaving the building, Bukele gave lawmakers one week to approve his loan proposal.

Lawmakers had previously failed to reach an agreement on Bukele’s proposal because of concerns about the size of the loan and the president’s justification of some of the expenses that he had included in the application for the loan.

President Bukele placed the right bet on the national army forces. He should not question the legitimacy of his actions, however. He has the security forces on his side amid the growth of security agencies’ budget. This requires continuing the policy of increased funding for security forces, which depends on the loyalty of the parliament. However, Bukele is also threatened by the politicization of the security forces in view of a high corruption level, law enforcement agencies included. Thus, Bukele needs to be backed by political elites, which will balance the actual dependence on the security forces.

El Salvador has one of the highest murder rates in the world. The country has the largest number of active gang-members in the region, an estimated 60,000, which exceeds the approximately 52,000 Salvadoran police and military officers. The gang social support base rises to 500,000 people – almost 8 per cent of total population – including sympathizers and former members, or calmados (gang lexicon for those who have desisted from gang activities).

According to figures from El Salvador’s National Civil Police, the average daily killings in the country fell from 9.2 in May 2019 — the month before Bukele took office — to 3.8 in January 2020. The government says that the decreased death count is a direct result of the Territorial Control Plan.

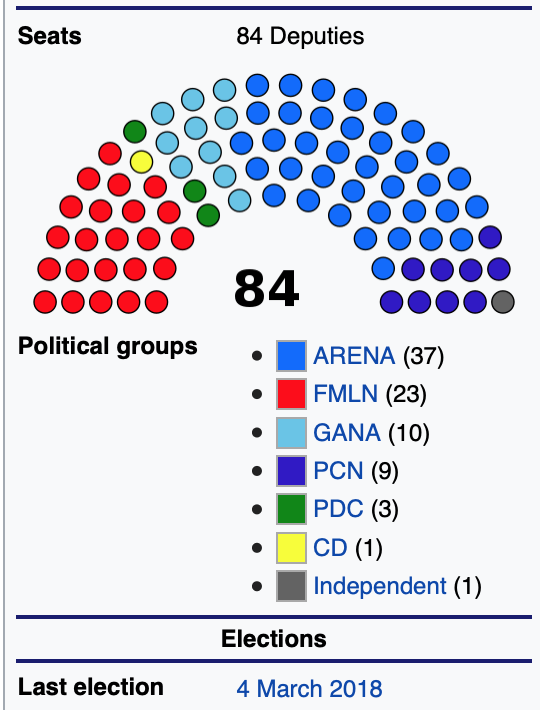

Groups like MS-13 have grown and thrived in El Salvador because the political class protects them. Prosecutors there showed that the country’s two main political parties (ARENA and FMLN) had colluded with MS-13 and other gangs, paying more than US$300,000 for help winning the 2014 presidential election.

Media investigations and testimony gathered by the prosecutor’s office suggest that, in the run-up to the 2014 presidential elections, ARENA and FMLN party bosses allegedly paid gangs $350,000 in exchange for votes in territories under their control. If true, the alleged deal – denied by both political parties – would point to gangs’ extraordinary power to influence electoral processes and control of opposition deputies in parliament.

Many officials confirm in private that communication with gangs inevitable.

Members of the Salvadoran police have been killed by the dozens in each of the past three years, most in attacks that investigators and experts blame on MS-13, an international street gang. At least nine officers were killed in the first month of this year.

This situation forces the President to demonstrate efforts to combat criminality in order to maintain the security forces support and prevent the growth of dissatisfaction with the authorities in the police and the army.

But the primary risk for the President is not to lose the image of a democrat and not to question the legitimacy of his actions. Meanwhile, opposition lawmakers, who have been in discussions with Bukele over the loan’s details, claimed he had no authority to call for the special session while the legislature was in session for regular business and in the absence of an actual national emergency. The Supreme Court already ruled that the Council’s order was not valid, and cautioned both Bukele and security forces not to exceed constitutional and legal jurisdiction.

They believe, the move by the soldiers, ordered by Bukele, drew condemnation from the opposition, which controls the Legislative Assembly. So, they labeled it an act of intimidation and accused the president of acting like a dictator. The opposition FMLN party said Bukele needed to “stop his threats which are typical of a dictatorship.”

Over the weekend, opposition lawmakers and some in the media accused the president of an autogolpe, or self-coup, akin to Peru’s Alberto Fujimori’s dissolution of the legislature in 1992.

By Monday morning, February 10th opposition lawmakers had canceled the session in which they were to vote on the loan, refusing to yield to Bukele’s machinations.

The president also lacks engagement with the opposition-controlled parliament. He needs more delicate work with the opposition, attracting some to his side, thus allowing him to form a more effective influence group and mitigate the risks of blocking decisions through parliament and initiating impeachment proceedings. Bukele could also work with foreign partners (USA, EU) more actively in fighting against corruption, especially the parliamentarians’ organized crime affiliations. This may become an incentive for some of them to support his initiatives.