Southeast Asia is a region that differs from other places in the world where China pursues its expansion policy in struggling for resources and influence. Although the PRC acts in the same manner, in Southeast Asia Beijing faces many problems despite its geographical neighborhood.

First of all, it can be explained by the high level of influence competition between China, the United States, Japan and India. The countries of Southeast Asia are rather heterogeneous economically and differ a lot in socio-cultural development. China is well-known in the region and it has a large diaspora. However, despite the fact that huaqiao traditionally have the upper hand in the economies of ASEAN states (especially in Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines), it is a big challenge to infiltrate agents of influence into the political elite, or to make an agreement with the local elite on many issues. That is why the massive expansion strategy and an intention to connect the region with a single infrastructure belt to strengthen economic ties do not bring immediate results.

Nevertheless, now ASEAN is China’s key economic partner. In the first quarter of 2020, ASEAN states left the European Union behind and became China’s major trading partner. Earlier, China has been the Association’s largest market, since 2007 on import and since 2010 on export. The key trading sphere that has demonstrated a high growth rate is electronics as Chinese companies are moving production facilities to the countries of the region and using local low-cost labor. Therefore, they make local governments as a part of their production and distribution chains. As a result, ASEAN countries are both China’s market competitors (due to the production of Western companies) and part of the Chinese global economy.

ASEAN is a major consumer of Chinese diverse products. China uses every effort to accelerate the trade increase and, ultimately, tie the economies of most ASEAN countries to China. Apart from this, initiatives to modernize the free trade zone with ASEAN, create zones of trade and economic cooperation, and the China-Indochina Peninsula economic corridor are also supposed to reach this economic strategic goal.

Creation of regional economic corridors with appropriate infrastructure supposedly to integrate the region and increase interconnection with China is another area of cooperation. Here we mean economic corridors between China and Vietnam, the Babu Bay Economic Zone, the Nanning-Singapore Economic Corridor, and the Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Zone. Beijing is making effort on creation of a pan-Asian road network integrating the highways of China, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore, as well as roads connecting the region’s key seaports. Beijing is interested in the project of the central trans-Asian highway of the high-speed railway on the following route: Yunnan Province — Laos — Vietnam — Cambodia — Thailand — Malaysia — Singapore. The Eurasian transcontinental route connecting the main cities and ports of Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore, and lying along the territory of Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey to Rotterdam (Netherlands) is equally important.

Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia are the key countries in the region that can be seen as China’s influence orbit. As of Myanmar, China is primarily interested in energy supply diversification. A gas pipeline with a capacity of 12 billion cubic meters per year, built by the Chinese state oil company CNPC, as well as an oil pipeline, run along the territory of Myanmar. In addition, Beijing is interested in the country’s carbon resources. According to OPEC, the volume of the explored gas reserves in Myanmar are 450 billion cubic meters; prospective gas, including the reserves in the shelf zone, exceeds 1.6 trillion cubic meters. Rare earth metals, copper, tin, ferronickel, jadeite and rubies of Myanmar are also in the zone of interest of China. The state is also important for the deployment of military bases (the Kyaukpyu port modernization) and electronic intelligence systems in the Cocos Islands that will ultimately strengthen Chinese positions in the Bay of Bengal.

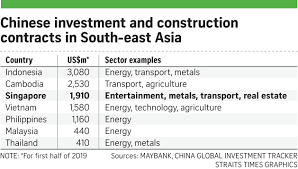

As of Laos, China is implementing an ambitious transport and infrastructure project that will tie the state to the PRC. The 414km standard-gauge single-track electrified line runs from China-Laos border at Boten to Vientiane. In the meantime, the Chinese section of the connecting road is already ready. The project itself is supposed to increase trade between the countries. Moreover, Chinese companies take interest in Laos’ energy projects, as well as copper and gold mining.

China is Cambodia’s largest investor and donor. Chinese companies actively invest in agriculture, light industry and tourism. China is extremely interested in the geographical location of Cambodia and its military operability. Last year, The Wall Street Journal publicized information about the bilateral agreement that would give China a 30-year access to the Cambodian naval base Ream located in the Gulf of Siam with automatic renewal every 10 years. In addition, the newspaper reported that China might gain access to the nearby Dara Sakor International Airport being built by a Chinese contractor. The airport is located in the middle of the Cambodian jungle in the Ko Kong region; its airstrip is clearly arranged for large military aircraft and fighters landing.

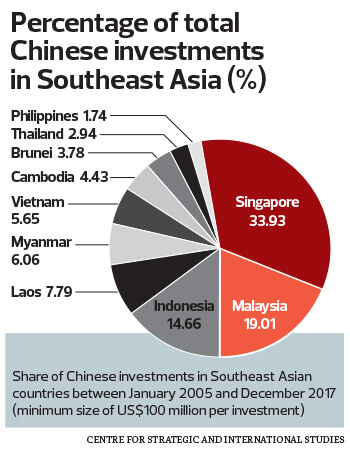

The PRC has a significant influence in Thailand, the country where China’s biggest diaspora lives. In addition, the state is a bulk consumer of Chinese goods, including the ones with a high level of added value: engineering and military-industrial complex. China’s key trade partner is Singapore where 74% of the local population is ethnic Chinese. However,Singapore is more than a trade hub; China is the main importer of Singaporean goods. In 2018, Singapore exported to China the goods worth $50 billion, that is 13% of all export. Electronics and high-tech items were exported the most.

Chinese expansion into Southeast Asia would have been more successful if it had not been energy resources-caused conflict in the East Sea. The PRC has been recently demonstrating power in the region by fuelling the conflict with Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia in the water area. The tensions arose because of the presence of about 5.4 billion barrels of explored oil reserves and 55.1 trillion cubic meters of natural gas in the region of the Paracel Islands and the Spartli archipelago; China is badly in need of these very reserves. This activity has an impact on relations with ASEAN states who are concerned about the Chinese threat. As a result, Beijing’s aggressive strategy in the region could outweigh the benefits from increased trade, infrastructure projects and investment.

The activity of Japan and India in the region challenges China’s plans to increase its influence dramatically. As of Delhi it is concerned about China’s geopolitical positions strengthening in the region and protection from cheap Chinese goods. Therefore, they block all global regional economic cooperation initiatives. Japan protects its own interests in its traditional region. The West tries to scale back China’s geopolitical ambitions in the region, fearing of the PRC’s power sharp increase in case of a significant regional position strengthening.

Naturally, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam are the only allies for these states. Despite the strengthening of cooperation with China, their growing economic potency and ambitions call into doubt Chinese fast expansion in the region. Nevertheless, China continues to implement large-scale regional projects that will heavily ‘tie’ the regional states to Beijing in the mid-term and change the current dispositions. The East Sea resources-caused overt conflict is the only condition that can reverse the situation.