The Russian Empire and the Soviet Union were extensively emerging imperial states, developing vast swathes and entering into constant armed conflicts with various ethnic groups in their path. This activity by Moscow through the centuries as often as not established the background for separatist tendencies, now observed in more than 20 regions of the modern Russian Federation.

Separatism in Russia has different connotation and ultimate beneficiaries today. It has its own features, conditioned by many factors depending on the region.

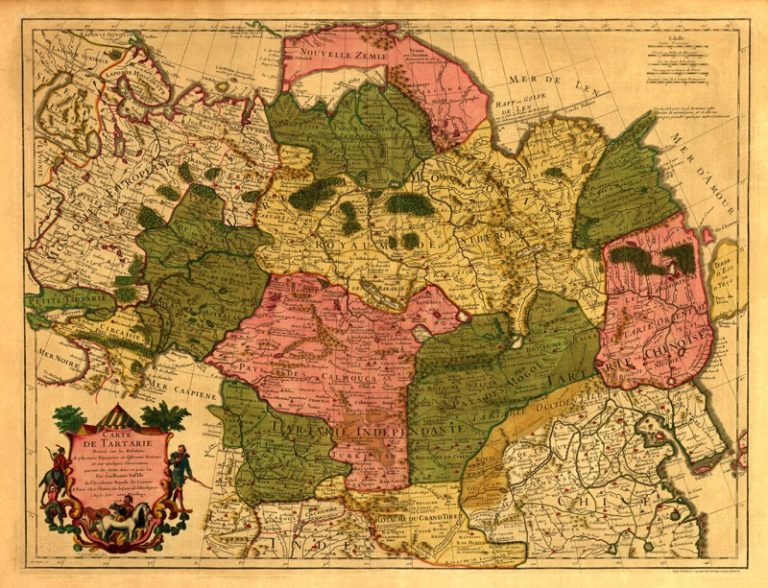

Ethnic factor and the echo of armed conflicts. The principality of Moscow, and then the Russian Empire, in the course of their extensive development, faced constant armed resistance from local residents, who sometimes represented not just other ethnic groups and other linguistic groups, but also other races. Many of the indigenous ethnic groups in modern Russia waged an armed struggle against the Moscow, later Russian invaders for centuries. A series of Caucasian wars, from the 18th to the 20th century, Bashkir uprisings, wars with the Tatars, Cheremis wars, Russian-Chukchi wars, Russian-Buryat wars, Yakut uprisings in the Soviet Union, etc. The history of the national liberation wars, therefore, had a significant impact on the culture and history of the native peoples. The centuries-old policy of assimilationism of local peoples by the Russians and the systemic downgrading of local cultures and religions, traditionally used by the Kremlin, had an impact as well. Therefore, many representatives of separatist movements in Russia’s parts today base their ideology precisely on opposing themselves to these historical processes.

Demographic factor. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, the Moscow elites fell short in their efforts to keep social and economic infrastructure in the regions of Russia. A large number of industrial enterprises closed down, and military units were destroyed, those having a social feature alongside – they ensured employment for the locals and supported social infrastructure. A significant part of the officers, members of their families, as well social workers, senior managers at industrial enterprises in the regions, were ethnically Russian. The Soviet Union spurred this strategy, seeking to raise the ethnic representation of the titular nation in almost all the regions that were “problematic” in terms of separatism. But Russia fell short in entirely getting on with it over the lack of resources. Thus, since the 90s of the last century, there has been a massive outflow of ethnic Russians from problem areas. Moreover, in some cases, Russians left not so much for socio-economic reasons but over domiciliary ethnic pressure. Indigenous peoples showed a higher birth rate, at the same time. The Republic of Tuva is one of the record holders. The number of ethnic Russians here was nearly a third in 1989. Only 16% of the total population remained Russians in 2010. That is, their number has fallen by half. In the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, the number of Russians fell by 14%, and the number of Chukchi (indigenous population) grew from 7% to 25%. The social base for separatist ideas enlarges, naturally, amid such demographic environment.

Religious factor. Russia proclaims religious freedom in the country. But practically, Moscow Orthodoxy has long become a part of the state ideology. This Christian movement is fully serving the state, its clergymen are tied with the authorities and intelligence agencies everywhere, representing the latter sometimes. Meanwhile, the ideas of Moscow Orthodoxy are strongly aggressive and extensive. The people in most parts where the separatist sentiments exist, practice other religions, however. Those are Sunni Islam, Tengrianism and Buddhism. In this case, the people there feel even more different from the federal center and view the Kremlin’s values as alien. Russia’s secret agencies are making strides toward religion, recruiting clergymen in the regions where the separatism is strong. But they do not always perform well. This is especially true for the regions where the concentration of Muslims and Buddhists is high or overwhelming.

Social and economic factor. Russia’s main natural-resource wealth is located outside its European part, where the Kremlin’s influence on social processes is also the weakest. State agents and security services here rather resemble representatives of the mother country, taking in tribute from business and local elites. Meanwhile, backdoor payments in Russia have clear size and boundaries, and the system itself is backed by the Kremlin, actually. That is viewed in a gray light by local elites, therefore, especially if they are national in nature. If the region is significantly rich in natural resources, fully or partially influenced by local elites, and the Kremlin is trying to get its share, the local elites favour separatist ideas often covertly or even half-openly. Tatarstan or the Republic of Sakha are a striking example of such policy. There is an opposite option as well. If the region is subsidized, local elites use the separatism to generate additional profit from the center. At the same time, they view themselves as the only guarantor for the stability of the region. The Caucasian republics, primarily the Chechen Republic and Dagestan provide an impressive example of such extortion.

External influence factor. Lots of RF territories lost their social ties with the center a long time ago, most notably Siberia and the Far East. Business and youth are focused on closer policy-makers. First of all, we are talking about China, Mongolia or Korea. Poverty rate in these parts of Russia and living standards in neighboring states concurrently spur the people on to mixed marriages and general cultural assimilation. We are most notably talking about the citizens of the PRC, marriages with them regarded as “good” in Russia’s neighboring regions.

Moreover, representatives of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey are active among Muslims both in the Caucasian republics and Tatarstan and Bashkortostan. As a result of continual contacts, assistance and interaction, both the elite and the people in these regions are ultimately focused not just on Moscow, but also on Riyadh, Doha or Ankara. Buryatia and Tuva’s economic and social links with Mongolia boost as well.

Each part of the Russian Federation by all means has unique features affecting the nature of separatist movements, their strength and future directions. This piece launches a series of papers where we will thoroughly describe the peculiarities of separatism in each of them.