The evidence proves Iran’s alliance and friendship with Al-Qaeda. Iran has long pursued ties to Sunni jihadists, including members of Al-Qaeda. The 9/11 Commission reports that in 1991 or 1992 Al–Qaeda and Iran had contacts in Sudan and that individuals linked to Al–Qaeda received training in Iran and Lebanon in the early 1990s. According to the FBI, between 1992 and 1996, several Al-Qaeda officials met with an Iranian religious official in Khartoum in order to arrange a “tripartite agreement between Al-Qaeda, the National Islamic Front of Sudan, and elements of the Government of Iran”. The Iranian security services and MOIS [ Ministry of Information and Security] supported a number of terrorist camps during the period Al-Qaeda was based in Khartoum.

The 9/11 Commission found that senior Al-Qaeda operatives and trainers traveled to Iran to receive training in explosives in other cases. Senior Al-Qaeda operatives graduated from these training courses in Iran, according to the testimony of Al-Qaeda defector Jamal al-Fadl.

Mahfouz Ibn El Waleed, a whip-thin Islamic scholar from Mauritania who was sent by bin Laden in 1995 to Iran met Quds Force Commander General Qassem Soleimani to discuss advanced military training, with Al-Qaeda fighters. Mahfouz was also invited in 1995 to attend a camp run by Hezbollah and sponsored by the Iranian Quds force in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley. The results of this audience are unknown.

After 1996, when Al-Qaeda moved its headquarters and training camps to Afghanistan, links with Iran became weaker.

However, the 9/11 Commission said, the Intelligence indicated the persistence of contacts between Iranian security officials and senior Al-Qaeda figures after Bin Ladin’s return to Afghanistan.

Several of the 9/11 hijackers transited Iran, taking advantage of its policy of not stamping the passports of those traveling from Afghanistan—a practice that hindered Saudi security agencies’ ability to detect the terrorists when they later returned to the Kingdom.

Since 9/11, Iran has cooperated fitfully with the United States in fighting various Sunni jihadists. At times Iran has provided considerable cooperation, such as sending many jihadists back to their home countries, where pro-U.S. security services can question them.

Tehran, however, has allowed several very senior Al–Qaeda figures, such as Saif al-Adel, Saad bin Ladin, and Abu Hafs the Mauritanian, to remain in Iran.

According to the intelligence, Saif Al-Adel has been living in the eastern border regions of Iran under the protection of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, or Pasdaran, an elite military force under the direct control of the Islamic republic’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Although Iran supposedly monitors individuals linked to Al-Qaeda, some reports indicate they played a major role in the May 2003 attacks in Saudi Arabia—suggesting Iran is not exercising true control over them.

On November 28, 2011 a U.S. District court issued a little-noticed ruling that effectively links Iran to Al-Qaeda on terrorism. In a 45-page opinion, Judge John D. Bates ruled that Iran “provided material aid and support to Al-Qaeda for the 1998 embassy bombings” in East Africa.

On February 16, 2012, the Treasury Department designated the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS) for its support of Al-Qaeda, as well as other terrorist organizations. According to Treasury, “MOIS has facilitated the movement of Al-Qaeda operatives in Iran and provided them with documents, identification cards, and passports. MOIS also provided money and weapons to Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)… and negotiated prisoner releases of AQI operatives.”

Iran appears to be keeping its options open with regard to the jihadists. On the one hand, it recognizes the heavy price to be paid if it openly backs them. Sectarian violence is a growing problem in Iraq. On the other hand, the jihadists are a potent weapon for Iran, which historically has tried to keep as many options open as possible.

This formerly clandestine network is the result of a specific “agreement” between the Iranian government and Al-Qaeda’s leadership.

Evidences

A former spokesman for the IRGC, Said Qasemi, shared a surprising revelation when he stated that the Iranian government sent agents to Bosnia and Herzegovina to train Al-Qaeda members under the cover of humanitarian workers for Iran’s Red Crescent.

Another Iranian official, Hossein Allahkaram, who is believed to be one of the operatives sent to Bosnia and Herzegovina, confirmed this, saying: “There used to be an Al-Qaeda branch in Bosnia and Herzegovina … They were connected to us in a number of ways. Even though they were training within their own base, when they engaged in weapons training they joined us in various activities.”

Al-Qaeda members traveled to Lebanon. According to the documents, Iran provided them with “money and arms and everything they need, and offered them training in Hezbollah camps in Lebanon, in return for striking American interests in Saudi Arabia.”

The IRGC, its elite Quds Force and the Intelligence Ministry are likely three Iranian institutions have long been instrumental in helping Al-Qaeda.

According to a report in The New York Times published on November 14, 2020, which cited information from intelligence officials, the Al-Qaeda’s deputy commander in Tehran al-Masri (Saleh, Abu Mariam, Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah Ali, Abu Mohammed) was killed in the Pasdaran area (the same area that is the residence of Saif Al-Adel) of Tehran on Aug. 7, 2020. This has again raised questions about the Iranian regime’s relationship with the terrorist organization and has provided a fresh reminder of the need to analyze the regime’s strategy based on using the organization as an asset and providing safe havens for its leaders.

Al Masri, was seen as a likely successor to Al-Qaeda’s current leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri. He was involved in the attacks on the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998. However, the Iranian Foreign Ministry dismissed the reports of Al-Masri’s killing on Iranian soil, describing them as “fake news.” Al-Qaeda has also not announced his death.

However according to the Iranian police data and Iranian state media there was a killing, in Tehran on Aug. 7. They reported about a Lebanese man and his daughter who had been killed in the northern Tehran neighbourhood of Pasdaran by unknown assailants on motorcycle. They identified the man as Habib Dawoud, a 58-year-old history teacher, and his daughter Mariam, 27. Al-Masri must be in his 50s, as his date of birth considered to be 1968, corresponds to Dawoud’s age.

This data gives a reason to think that al-Masri was killed along with his daughter, Maryam Abdullah Ahmad Abdullah.

The theocratic Iranian establishment most likely provided Al-Masri with the resources to carry out his campaigns against the US and Gulf states.

Maryam was the widow of former Al-Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden’s son (Hamza bin Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden). So names of al-Masri’s daughter and woman who was killed in Tehran are the same. This increases the likelihood of the al-Masri killing version in Tehran.

The CIA released video shows Hamza bin Laden’s wedding, providing the first publicly-available images of him as a young man. The video was found in the materials seized during the raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound in May 2011: images, and computer files. The wedding took place in Iran, where Hamza was held in a form of house arrest or imprisonment on and off for several years. Along with other members of the bin Laden family, Hamza relocated to Iran after the 9/11 hijackings supposedly in mid-2002.

Many members of Al-Qaeda and its affiliated groups found they had no choice but to escape to Iran, particularly in light of the Iranian regime sharing the organization’s animosity toward the US and feeling they had no hope of fleeing to Pakistan given the strong CIA presence there.

Masri had been in Iran’s “custody” since 2003 but had been living freely in an upscale suburb of Tehran since 2015.

Many Al-Qaeda figures were welcomed inside the country. But ultimately their stay on Iranian soil became a highly contentious issue.

Supposedly in the beginning of 2000s Al-Qaeda wives and daughters, along with hundreds of low-level volunteers were escorted to Tehran. The women were put up at the four-star Howeyzeh Hotel on Taleqani Street. Husbands and unmarried fighters stayed across the road at the Amir Hotel. From there, the Quds Force gave them false travel documents that disguised them as Iraqi Shia refugees and flew them out to other countries, where they either settled or went on to join other conflicts.

The wedding video, released by the CIA, shows a senior Al-Qaeda leader, Mohammed Islambouli, sitting next to Hamza, to his right or close by, throughout the video. Islambouli, an Egyptian who is the brother of Anwar Sadat’s assassin, also lived in Iran for years.

Hamza named his mentors as Saif al Adel, Ahmed Hassan Abu al-Khayr, Abu Muhammad al-Masri, Sulayman Abu Ghaith — all of whom were senior Al-Qaeda figures detained alongside Hamza in Iran.

On July 20, 2016, the U.S. government again revealed Iran’s collaboration with Al-Qaeda. The

Treasury Department blacklisted three members of Al-Qaeda living in Iran, saying they had helped

the jihadist group. Yisra Muhammad Ibrahim Bayumi, mediated with Iranian authorities as of early 2015, the Treasury said, and helped Al-Qaeda members living in Iran. Bayumi has been residing in Iran since 2014 and had been able to facilitate Al-Qaeda funds transfers in 2015, suggesting he had some freedom to operate since moving to Iran. Abu Bakr Muhammad Ghumayn had control of the group’s financing and organization inside Iran as of 2015.

Ideological issues

The regime in Tehran insists on sectarian differences and conflicting ideological views as supposedly compelling evidence of the lack of any connection between Tehran and Al-Qaeda, and it reiterates the animosity between the two sides. However, a closer look at both the trajectory of relations between the two sides and their ideological similarities will quickly reveal the deep-rooted ties between them and show the Iranian regime’s success in forging an alliance with Al-Qaeda and employing its operatives to meet Iranian objectives.

In overcoming traditional Shiite-Sunni divides, Shia and Sunni terrorist groups have goal-oriented rather than rule-oriented doctrine. Iranian support for Sunni Muslim-dominated groups involved in the Palestinian struggle, including Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad prove this suppose.

In theory, there are two different schools of thought within Al-Qaeda in relation to dealing with Shiites in general and with Iran in particular. The first school of thought, spearheaded by Ayman Al-Zawahiri and Abu Mohammed Al-Maqdisi, believes that targeting Iranians and Shiites in general is not a priority for the organization because they are excused for their ignorance of the “true” understanding of Islam, which Al-Qaeda claims to monopolize. Also, this school is somewhat more lenient and flexible in its attitude toward Shiites when compared to the second school of thought, which will be discussed in the following lines. According to this first school of thought, precedence should be given to confronting the more evident enemy: The West, the US and those aligned with them.

The second school of thought within Al-Qaeda was spearheaded by Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, a student of Al-Maqdisi and the assassinated leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq, who believed in the necessity of expanding the organization’s terrorist operations against Shiites with the aim of sparking a Sunni-Shiite civil war in Iraq.

Reasons to cooperate

Iran and Al-Qaeda share several common interests. Tehran is attracted to the organization because they both view America as their main enemy, and the group has carried out several successful terrorist attacks against the US. Al-Qaeda is also a threat to Gulf states which Iran views as regional rivals.

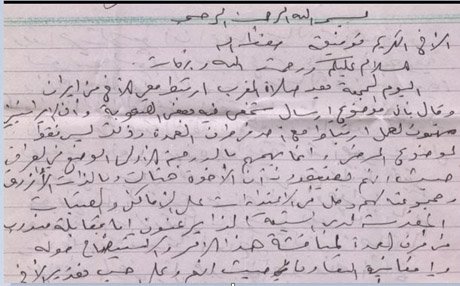

A document presumably authored by Osama bin Laden in 2007 refers to Iran as Al-Qaeda’s “main artery for funds, personnel, and communication.” That same letter referred to the “hostages” held by Iran, meaning those Al-Qaeda figures who were held in some form of detention and not allowed to freely operate.

«Under the terms of the agreement between Al-Qaeda and Iran,” the US Treasury reported, “Al-Qaeda must refrain from conducting any operations within Iranian territory and recruiting operatives inside Iran while keeping Iranian authorities informed of their activities.” As long as Al-Qaeda didn’t violate these terms, “the Government of Iran gave the Iran-based Al-Qaeda network freedom of operation and uninhibited ability to travel for extremists and their families.”

According to the 2012 statement by the State Department, Iran “allowed AQ facilitators Muhsin al-Fadhli and Adel Radi Saqr al-Wahabi al-Harbi to operate a core facilitation pipeline through Iran, enabling AQ to move funds and fighters to South Asia and to Syria.” Fadhli “began working with the Iran-based AQ facilitation network in 2009,” was “later arrested by Iranian authorities,” but then released in 2011 so he could assume “leadership of the Iran-based AQ facilitation network.”

In September 2015, Sky News reported that Iran reached an agreement with Al-Qaeda members in which they “agreed not to turn their guns on the regime of Bashar al-Assad.” Instead, al-Zawahiri says they are in Syria to “develop external attacks, construct and test improvised explosive devices and recruit Westerners to conduct operations.”

Some intelligence agencies believe, however, AQ leaders, stationed in Iran might be able to travel to Syria, where they could make use of the ungoverned and chaotic landscape to plot attacks outside the country – having agreed not to turn their guns on the regime of Bashar al Assad, which is backed by Tehran.

By having Al-Qaeda members and affiliates on its soil, Iran found additional assets for extending its terrorist capabilities in the region and beyond. These assets had the potential to carry out whatever terrorist operations the Iranian regime wished to mount or potentially serve as a useful bargaining chip with the US, to be swapped — if necessary — to achieve its interests against the US. Such attacks can be carried without suspicion of Tehran’s involvement in them, especially in the Gulf region.

Al-Qaeda provides the Iranian authorities with the opportunity to increase their military presence and influence in other countries, such as Iraq, on the pretext of fighting against terrorist groups. We think this is the same motivation as in case with the Taliban. This is why Al-Qaeda has carried out attacks in many countries but has not targeted Iran.

According to the documents seized after the raid on the compound in Abbottabad, Bin Laden was not against attacking Iran in principle; he simply did not think the costs of such action were worth it.

So, Iranian authorities have guarantees of Al-Qaeda neutrality toward Tehran regime.

According to the intelligence sources, while the Shi’a theocracy of Iran and the Sunni extremist group Al-Qaeda were theoretical enemies, there has been an “understanding” that the two would avoid attacks on one another and focus on battling the “shared threat” of the West.

Bin Laden’s files show that he was troubled by Iran’s attempt to expand across the Middle East and he conceived of a plan to combat the Shiite jihadists’ growing footprint. This is why the two sides are clearly at odds in Syria and Yemen, where they have fought each other and affiliated proxies for several years.

Having contacts with senior Al-Qaeda commanders, Tehran has capacity to establish indirect talks with Sunni Gulf regimes as an effective mechanism of Iranian foreign policy.

Al-Qaeda’s modus operandi is anchored in efforts to destabilize the region and create chaos, which is a ripe environment that the Iranian regime, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its proxies and militia groups can exploit and prosper from. Meanwhile, Al-Zarqawi directed his extremist vision toward the Shiites in Iraq in order to cause the greatest possible disruption for the remaining US troops in Iraq so that to drive them out of the country, enabling Iran to take control of Iraq. It is worth noting that Al-Zarqawi had first fled to Iran following the 2001 US invasion of Afghanistan before moving to Iraq.