Tensions between Ethiopia and Sudan continued to escalate, less than a week after Sudan accused an Ethiopian military aircraft of crossing into Sudan.

The violation of Sudanese airspace and the attacks on civilians are the latest provocative acts of Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali, who probably might decide to occupy the disputed border territories of Al-Fashqa, an area of fertile agricultural land within Sudanese territory. Addis Ababa claims Al-Fashqa as Ethiopian territory as hundreds of miles of Ethiopians live there.

During the rule of ousted Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, Khartoum largely turned a blind eye to the country’s territorial incursion. But Sudan’s transitional authorities have initiated talks with Ethiopia in a bid to have Ethiopian farmers withdraw.

We think that probability of Ethiopian war against Sudan is less than 15%. It would directly involve Egypt and Eritrea. The monarchies of the Arabian Peninsula would split in supporting Egypt or Ethiopia. Turkey would take advantage of it to enter the case as Syria and Libya demonstrate. The Islamic terrorist group Al-Shabaab (youth), affiliated with DAESH, would take advantage of it to sow chaos in the Ethiopian Somali Region.

The attention paid by the Ethiopian Premier to the territories of Al-Fashqa and hidden by the nationalist rhetoric is an act obliged by a pact made in August – September 2020 between Premier Abiy and the Amhara leadership to defeat the TPLF leadership.

The prospect of Ethiopia opening up another major military front is worrying because the country is already very fragile and if it were to have more internal instability that would also have regional ramifications. But a protracted conflict is not in the best interests of the Sudanese interim government, or the Sudanese people. According to estimations, Sudan cannot afford this conflict at the moment. A war between the two states means catastrophic consequences, as both armies are almost equivalent. The armored units and the aviation of the two countries are also equivalent. But the number of paramilitary forces of both Sudan and Ethiopia points at high risks of violence and civilian losses by both sides.

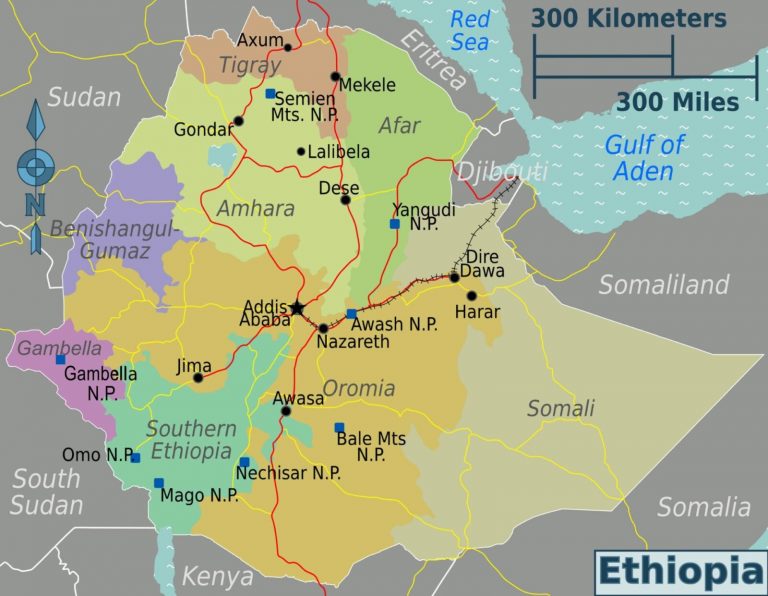

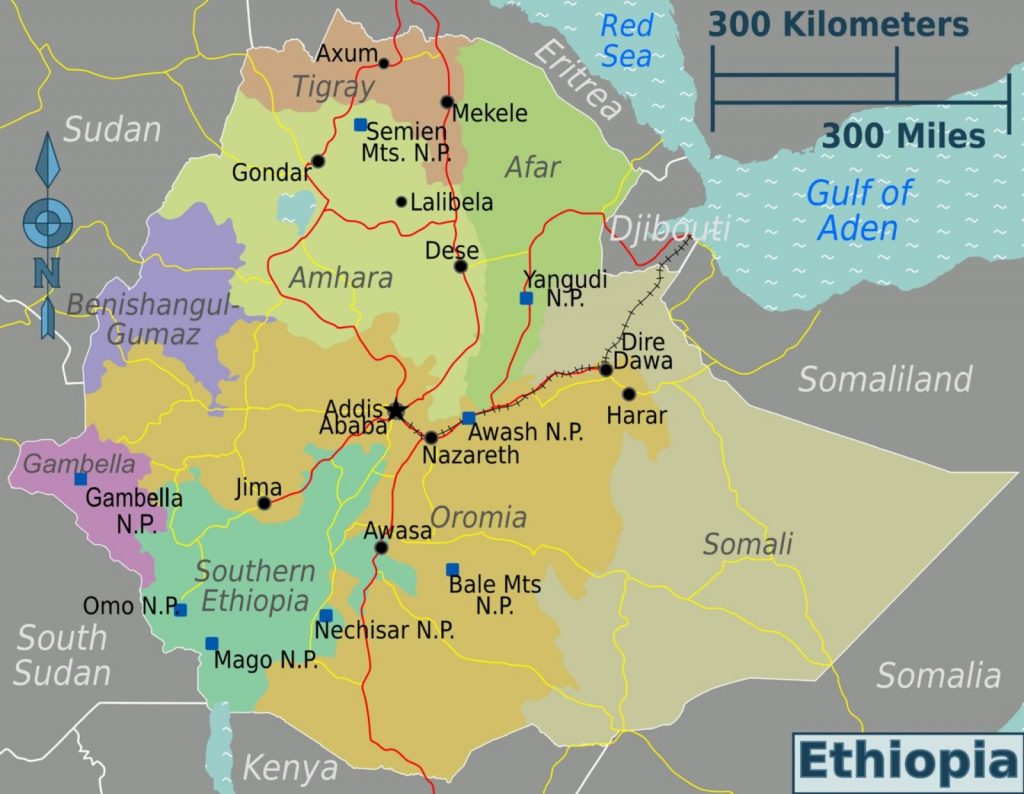

The Sudanese army reportedly advanced to the west of Ethiopia’s Gondar region near the border, while residents and government officials claimed some members of the military looted cattle and burned farmlands belonging to Ethiopian farmers. There was no Sudanese decision to wage war against Ethiopia, but the decision was issued to allow the Sudanese forces to control all of its territory.

Ethiopia-Sudan relations have long hinged on mutual suspicion and disagreements over territory.

A fragile peace between the two countries began to unravel in November 2020 after conflict broke out in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region along the disputed border.

The border between Ethiopia and Sudan has been disputed for more than a century, with a number of failed attempts to negotiate an agreement on exactly where the border should run. The border was drawn following a series of treaties between Ethiopia and the colonial powers of Britain and Italy. However, to date, this boundary lacks clear demarcation lines.

Treaties drawn up in 1902 and 1907 between Ethiopia and Britain were intended to define the border between Sudan and Ethiopia.

But Ethiopia has long claimed that parts of the land given to Sudan actually belong to them.

Although there was Ethiopian agriculture activity in these areas, it didn’t mean it was Ethiopian land.

Decades of friction and negotiations seemingly ended in 2008 when a ‘soft border’ compromise was reached between the countries.

However, this agreement began to unravel after Ethiopia’s Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) was removed from power in 2018.

Ethiopia is also still reeling from an ongoing armed conflict in the northern Tigray region near the Sudanese border, possibly triggering fears on the Sudan’s side that the Ethiopians may try and take some of the disputed areas amid the chaos.

Amhara nationalists and other elements in Amhara regional state reclaimed territory in Tigray that they say historically was Amhara. They are also looking at regions that were historically part of Ethiopia, so this have led to some concerns in Sudan that the Amhara farmers will consolidate their occupation of these areas which Sudan considered Sudanese.

When the Ethiopian National Defense forces moved to Tigray region on November 4, 2020 for the law enforcement majors, the Sudanese army took the advantage and entered deep inside Ethiopian territory, looted properties, burned camps, attacked the Ethiopians, displacing thousands.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam also looms over Ethiopia and Sudan’s tense relationship. So, Cairo may see the tensions between Khartoum and Addis Ababa as the way to partially solve ERD issue.

Ethiopia began building the dam in April 2011 about 20 kilometers east of Sudan’s border. Once complete, it will be Africa’s largest hydroelectric power plant. However, no agreement on the use of Nile waters has been reached – much to the concern of Sudan, which relies heavily on the Nile reservoirs for agriculture.

Sudan was supportive of the Renaissance Dam, which of course can be beneficial to Sudan in terms of electricity, reducing flooding, enhancing irrigation. However, Sudan wants the joint operation of the dam.

Borders in the Horn of Africa are fiercely disputed. Ethiopia fought a war with Somalia in 1977 over the disputed region of the Ogaden.

In 1998 it fought Eritrea over a small piece of contested land called Badme.

About 80,000 soldiers died in that war which led to deep bitterness between the countries, especially as Ethiopia refused to withdraw from Badme town even though the International Court of Justice awarded most of the territory to Eritrea.

It was reoccupied by Eritrean troops during the fighting in Tigray in November 2020. Since 1080s the influence of Islamists over the government in Khartoum began to pose a growing threat to the communist regime in Addis Ababa. As such, Ethiopia was supporting the Sudanese People Liberation Army (SPLA) to take control over Khartoum. To counter the support that Ethiopia was giving to the SPLA, Khartoum also started to support the various Eritrean and Tigrayan rebel movements inside Ethiopia. Among these rebel groups were the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) of Meles Zenawi and the Eritrean president Isaias Afewerki. Ethiopian borders were open for SPLA rebels, who hid out in its borderlands from the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). In November 1987, the Ethiopian army supported the SPLA when they captured Kurmuk in Sudan’s Blue Nile state.