The Ortega government speaks out against Nicaraguan opposition, removing all political credibility for the country’s government and electoral system. Systematic and repeated violations of the rule of law delegitimize the November electoral process before it has even begun.

A fraught election could further isolate the government internationally and rekindle domestic unrest.

The risks of an egregiously unfair election – which might feature miscounted votes, harassment of opposition politicians and the prohibition of their parties – is likely to trigger public ire.

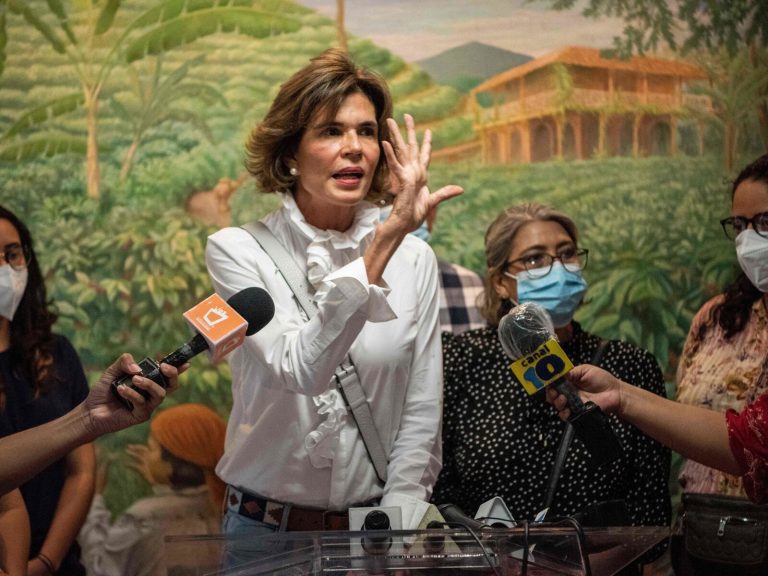

Nicaraguan police arrested Cristiana Chamorro, the leading opposition candidate for president, in the latest in a string of moves that have curtailed any challenge to President Daniel Ortega in the November election this year. The arrest came shortly before a virtual press conference scheduled for 12pm local time on Wednesday, June 2.

Chamorro, 67, is one of Nicaragua’s most storied political families. Chamorro’s mother, Violeta Chamorro, defeated Ortega in the 1990 presidential elections, putting an end to the 11-year reign of his leftist Sandinista movement.

Chamorro is vice president of La Prensa, an opposition newspaper formerly led by her father, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro. His 1978 assassination prompted many Nicaraguans to support the Sandinista rebels, who eventually toppled the dictatorship of President Anastasio Somoza.

The daughter of assassinated newspaper editor Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal (critic of Somoza regime) and former Nicaraguan president Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, this year Cristiana Chamorro became a vice-president of the Nicaragua’s largest paper La Prensa.

Chamorro also became director of the press freedom foundation in her mother’s name, Foundation Violeta Barrios de Chamorro (VBDC). She served in this capacity until January 2021, and in February 2021 the Foundation ceased operations after the Ortega government, which had returned to power in 2007, announced a new law that all groups receiving funding from outside Nicaragua would be required to register as foreign agents. Rather than accept foreign status, the Foundation ceased operations. She is widely seen as a challenger to President Daniel Ortega, who is running for a fourth consecutive term in November.

Locals and diplomats inform that the government installed total control in the state, using undercover agents, local sympathisers, ex-convicts and even parking valets to conduct surveillance. Dozens of prominent opponents report that they live under constant intimidation, with police almost permanently stationed in front of their houses or following them in the street, preventing them from moving about freely.

Nicaragua’s fractured opposition faces internal struggles. Opposition groups have spent more than two years trying to come to an agreement over how to form a single coalition to battle Ortega. The right-wing Citizen Alliance had been during April this year locked in intense talks with the Democratic Restoration Party (PRD), part of a National Coalition umbrella grouping that represents anti-Ortega leftists, evangelical Christians, students and other groups.

Thus, Ortega is likely to be re-elected if the opposition is divided.

While most opposition factions insist on peaceful dissent, making armed insurrection unlikely, the risk of local flare-ups of violence, set off by electoral fraud or an intensified state crackdown, cannot be excluded.

Violence could also erupt if the opposition wins on a sudden, however unlikely such outcome might seem, especially if the new government opts to embark upon anti-Sandinista witch hunt in state institutions.

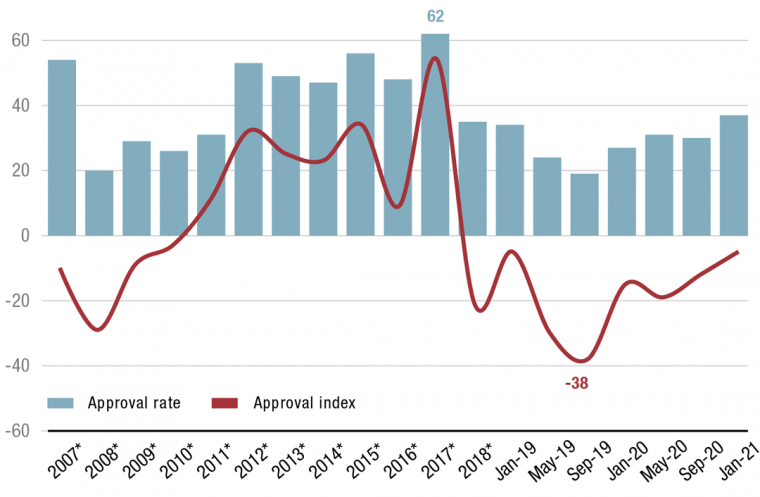

Only a third of the population now backs the president. Though he is deeply unpopular across vast sections of Nicaragua society in the wake of the rights abuses in 2018, the socialist leader has steadfast support of his Sandinista party base.

The Ortega’s government has relied on repression to keep the opposition at bay. Rosario Murillo, the vice president and first lady, reportedly aims to assume the reins, though she seems to enjoy even less support.

In 2021, Chamorro was a pre-candidate for president although she foremost supports a unified opposition.

She was accused of abusive management and money laundering, according to a communique issued by judicial authorities. Police searched her residence in Managua for several hours and placed her under house arrest. The detention was assailed by human rights advocates in Nicaragua and abroad. However, her arrest reflects Ortega’s fear of free and fair elections.

This arrest shows that scenario of growing risks for cheating and greater repressive crackdown if the opposition succeeds in forging a common front is not relevant, as Ortega’s government might start repressing the opposition just to secure his victory, despite opposition unity.

The Ortega government accused Chamorro of “abusive management” and “ideological falsehood” because of her role running the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation for Reconciliation and Democracy, a press freedom group.

Ortega returned to power in 2007 and has been reelected twice since then in elections marred by irregularities. He has significantly concentrated power and grown more authoritarian.

The U.S. government has slapped financial sanctions on more than two dozen Nicaraguan officials it accuses of undermining democracy, including Vice President Rosario Murillo, Ortega’s wife.

Ortega and his allies have taken steps to sideline potential challengers, including stripping the legal registration from one party and passing a law allowing authorities to disqualify candidates as “traitors to the homeland.”

Elections are unlikely to stabilize the situation in Nicaragua and enhance democracy. The vote could well cause long-running tensions to escalate, particularly if there are credible allegations that it has not been cleanly run.

Nicaragua is ready for international isolation. Such scenario would push Nicaragua to non-democratic countries like Iran, Russia and China.