Hezbollah involved in the drug trade. American law enforcement discovered Hezbollah’s drug activity by chance in 2006, when Colombian wiretaps monitoring a Medellin- based drug cartel known as the Oficina del Envigado picked up conversations in Arabic. The DEA brought in a translator who explained that Hezbollah was arranging multi-ton shipments of cocaine to the Middle East. In the ensuing investigation, codenamed Operation Titan (originally launched in 2004 to target the Oficina), the DEA opened a Pandora’s Box. This led to Project Cassandra, a decade-long operation launched in 2007 that sought to stop Hezbollah from trafficking drugs into the US and Europe. Despite being noted for its historical affiliation with drug trafficking and other organized crime activities, Oficina de Envigado’s criminal activities were no longer centered on direct involvement in such activity by 2019 and are now mainly focused on providing services to lower level drug traffickers and mafia groups. It operates throughout Colombia, but mainly in the cities of Medellín and Envigado. It also controlled extortion, gambling, and money laundering businesses within the Valle de Aburrá that surrounds Medellín. It positioned itself as the chief mediator and debt collector in drug trafficking disputes and maintained major connections with the paracos (Colombian paramilitaries) and guerillas.

On January 6, 2021, the Gulf news network Al Arabiya claimed, that in late 2016, a high-placed Hezbollah operative named Nasser Abbas Bahmad came to what is known as the Tri-Border Area (Triple Frontera), where the frontiers of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay meet. His apparent mission was to establish a supply line of multi-ton shipments of cocaine from Latin America to overseas markets in order to generate funds for the Lebanese terrorist group Hezbollah.

Since Hezbollah’s inception, Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah insists on denying the group’s growing global footprint in the world of transnational organized crime in order to maintain legitimacy in Lebanon—even to the point of admitting Hezbollah’s financial support from Iran in order to dis- tract from its other illicit sources of revenue.

Howevrer, investigative pieces soon followed in the Argentinian and Paraguayan press. And they are onto something: a law enforcement source from one of the three countries told this author, on condition of anonymity, that Bahmad and his business partner, Australian-Lebanese national Hanan Hamdan, were put on a US watchlist in December 2020.

Cassandra’s key finding was that Hezbollah’s shipments of cocaine were not a small sideshow by loosely affiliated individuals but a multibillion dollar, worldwide operation orchestrated by top officials within Hezbollah’s inner circle.

The DEA revealed the full extent of Hezbollah’s terror-crime nexus and its centrality to Hezbollah’s organizational structure in February 2016, when Operation Cedar led to multiple arrests across Europe— including Mansour, the charcoal trader. By then, the DEA had been chasing Hezbollah money-laundering operations on behalf of drug cartels for nearly a decade. French raids led to the arrests of prominent Hezbollah facilitators Mohamad Noureddine and Hamdi Zaher El Dine. Four days after their arrests, the US Treasury Department sanctioned both of them.

Referring to the sanctioned duo, then-Acting Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Adam J. Szubin said that Hezbollah relied on such facilitators “to launder criminal proceeds for use in terrorism and political destabilization.” In particular, this money was financing Hezbollah’s arms procurement to sustain its military engagement in Syria.

In Syria, Hezbollah has used its drug proceeds to buy arms for fighters on behalf of the Assad regime, with senior commander Ali Fayyad and another individual believed to be involved in the purchases.Hezbollah also protects smuggling routes in the so-called Shia Crescent, including in Syria. Reporting indicates that marijuana, Captagon, and other drugs are now being heavily trafficked by Syrian military intelligence.

Treasury stopped short of explicitly identifying the two as Hezbollah members, but said they were providing material support to Adham Tabaja, whom Treasury had sanctioned in 2015 as a leading Hezbollah member and financier.

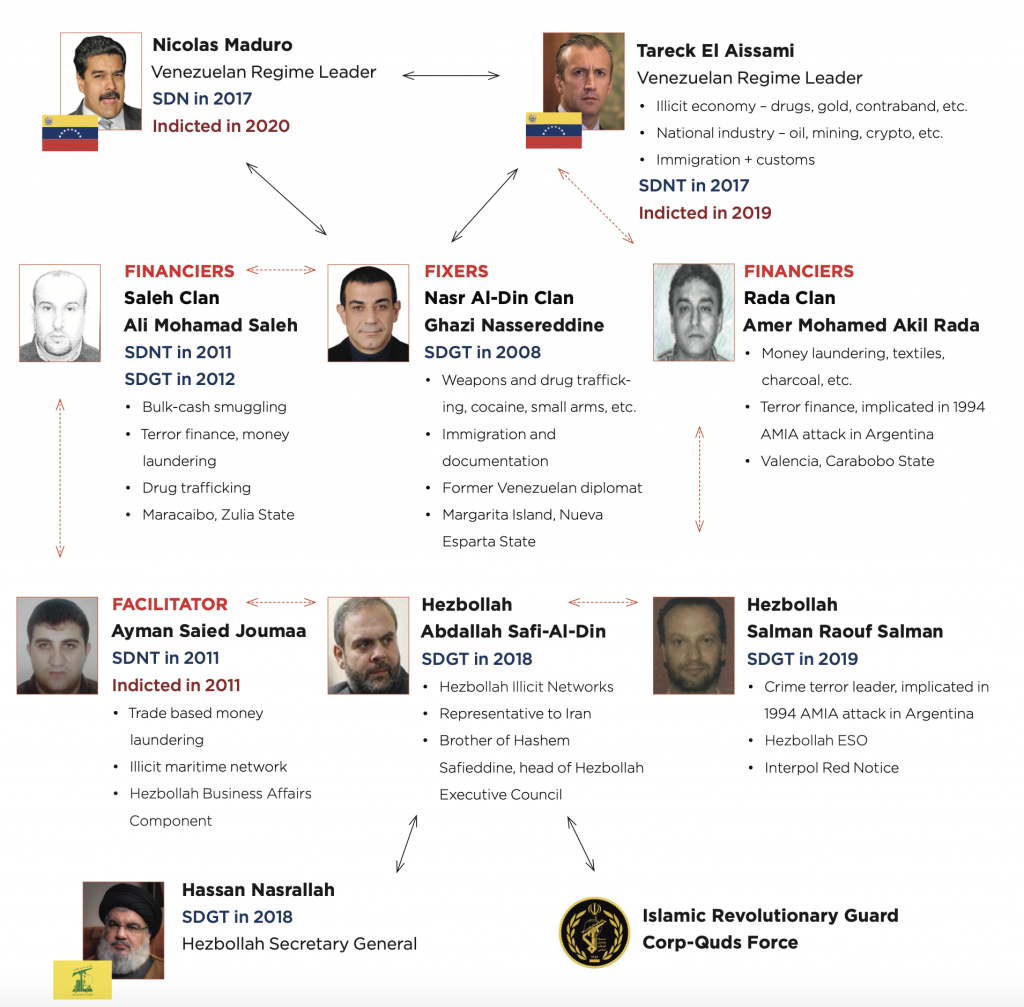

The DEA’s February 2016 announcement also detailed the hierarchical structure overseeing Hezbollah’s illicit financial operations since as early as 2007. The DEA named it the BAC, an acronym for the Business Affairs Component of Hezbollah’s External Security Operation. It identified the BAC’s founder as the late Hezbollah arch-terrorist Imad Mughniyeh. After his death in a car bomb in Damascus in February 2008, the BAC’s leadership was bequeathed to Abdallah Safieddine, Hezbollah’s representative in Iran, and his right-hand man, Tabaja.

The targeted ring involved shipments of cocaine to Europe, paid for in euros, which Hezbollah couriers then transferred to the Middle East. The funds are then sent back to drug traffickers in Colombia through Hawala — an informal distribution system that uses brokers to transfer money and currency. A large amount of these proceeds reportedly transit through Lebanon, and a “significant percentage” remains in Hezbollah coffers.

Hezbollah also made more than €20 million a month selling its own cocaine, in addition to laundering hundreds of millions of euros of cocaine proceeds on behalf of the cartels, retaining a fee. During the arrests, local authorities of the seven European countries involved in the investigation seized €500,000 in cash, luxury watches worth $9 million that Hezbollah couriers intended to transport to the Middle East for sale at inflated prices, and property worth millions.* These figures are peanuts compared to how much the network laundered overall.

Project Cassandra turned out to have been well named. It clarified, to anyone listening, the extent and depth of Hezbollah’s involvement in organized crime. Narco-terrorism—a hybrid threat involving the toxic convergence of organized crime and terror finance networks— should have spurred more aggressive investigations, prosecutions, and sanctions. For Latin American governments in particular, which preside over societies that are being crippled by the Hezbollah-backed criminal syndicates, the narco-terrorism revelations should have been a wake-up call.

in 2014, it was reported that Lebanese traffickers were helping the Brazilian prison gang the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital -PCC) to access weapons.

The large cocaine shipments tied to Hezbollah’s money-laundering networks used to flow from Colombia and Venezuela, and with good reason. Colombia remains Latin America’s largest producer of the white powder, and Venezuela, under the Iran-friendly narco-regime of Nicolas Maduro, is a key transit point for cocaine shipments. If Hezbollah is now involved in establishing a major cocaine supply line in the Triple Frontera, something must have changed in its modus operandi.

While funding is the main purpose of Hezbollah’s drug trafficking, it also has another, more nefarious purpose: To weaken its enemies by trying to encourage drug addiction among their fighting-age populations. Reports from Syria by Al-Arabiya, Al-Hurra, Asharq Al-Awsat and others have documented how Hezbollah and its affiliated groups have worked to demoralize communities in Syria and Lebanon by turning local economies into drug manufacturing areas and facilitating youth drug use.

Previously, LRI underlined, that Hezbollah leader Nasrallah has issued religious ordinances saying that selling drugs to hostile communities is a moral duty consistent with the idea of resistance.

Sheikh Mohamad Yazbek, Hezbollah’s spiritual leader in the Beka’a Valley region and a member of the group’s Supreme Shura Council, published a fatwa allowing the production and sale of counterfeit Captagon tablets on condition that they not be used by members of the Shi’ite community.

While fragile communities in war-torn areas have been decimated by Hezbollah’s drugs, Gulf countries are more difficult targets. Precautionary measures such as the ban on imports from Lebanon should move the Lebanese authorities to crack down on this growing trade in drugs, and they should join law enforcement agencies around the world to fight it. Otherwise, economic ruin would be the wages of negligence, not to mention a serious addiction problem.