Guatemala is going through political turmoil amid total corruption and race for power by elites closely tied to the criminals. In the mid-run, there is no reason to believe the situation will change. On the contrary, it is reasonable to suppose that the government would fall more under the sway of drug gangs and non-democratic influence from abroad.

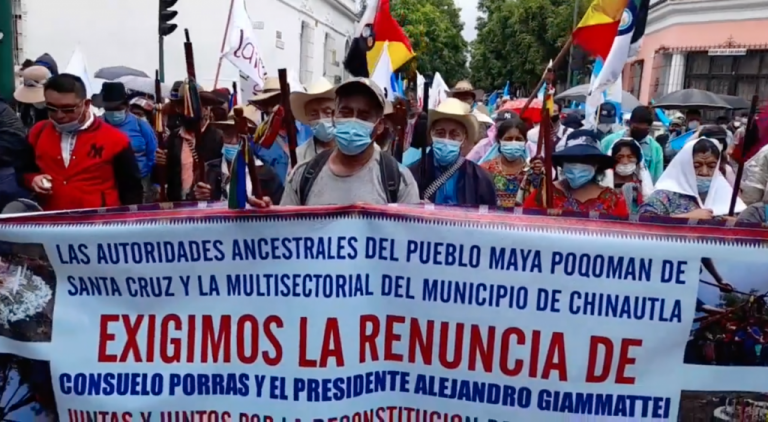

Leaders of indigenous communities, social groups and student organizations have joined anti-presidential protests in Guatemala to demand the resignation of the right-wing President Alejandro Giammattei and other government officials facing allegations of corruption.

The President Alejandro Giammattei, a former director of the Guatemalan penitentiary system is suspected in corrupt relations with investors related to nickel mining companies that operate illegally in Guatemala and that are violating the rights of the Maya K’iche’ communities that live in the region of El Estor, Izabal, an area of exploitation, of monocultures, of mining and that have lived very hard the effects of the pandemic and the climate crisis. A lot of Indigenous communities have been militarized during the pandemic.

Protesters are also denouncing corruption, a worsening economic crisis and the government’s catastrophic mishandling of the pandemic. COVID-19 cases continue to skyrocket, with hospitals collapsing or on the verge. Meanwhile, less than 2% of the population of Guatemala has been vaccinated. The government of Guatemala signed an agreement with Russia to supply so-called Sputnik V vaccine, but Moscow failed to make good on the deal in full, thus bringing Guatemala to the brink of pandemic disaster. The delay sparked criticism of the government and calls for an investigation, while ombudsman Jordan Rodas and dozens of social, educational and humanitarian organisations clamored against Giammattei.

As the result, President Alejandro Giammattei announced that Guatemala has cancelled its order of a second batch of eight million Russian-made Covid-19 vaccines due to a delivery delay of a previous order. Giammattei said that the cancelled purchase corresponded to the “50 percent that was planned to be spent on Sputnik vaccines”.

The national strike was called by Indigenous leaders, who vowed they won’t stop until there is radical change in Guatemala.

Civil protests flooded the country following the decision by Guatemala’s Attorney General Maria Porras to remove anti-corruption leader Juan Francisco Sandoval from his post as the head of Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity (FECI) in mid-July 2021. Hours later, Sandoval fled the country. That step drew denunciation from the world and popular discontent in the country.

The Center against Corruption and Impunity in the North of Central America (CCINOC) also hit out at Porras’ decision, saying it would create “setbacks in the fight against corruption in the region.”

In July there were comments on the alleged visit to Giammattei by Russian citizens who brought money suitcases. Four days before, the anti-corruption prosecutor Juan Francisco Sandoval indicated that he had information and inquiries about the delivery of money to the Government by Russian citizens last April, without elaborating on the matter. The scenario is similar to the case of Russian vaccine supply to Slovakia, triggering government resignation and corruption charges.

The decision to remove Sandoval fits a pattern of behaviour that indicates a lack of commitment to the rule of law and independent judicial and prosecutorial processes. The U.S. has been a vocal supporter of Sandoval’s work, which included investigating and litigating cases against former officials, presidents and business leaders in Guatemala. The State Department declared him an “anti-corruption champion” in a February award.

According to Sandoval, Porras also tried to block investigations into political mafias seeking to stack Guatemala’s courts by instructing prosecutors to avoid investigating certain individuals such as Néster Vásquez, a current Constitutional Court magistrate linked to the court mafias. Political elites have maneuvered for years to place allies in the lower Supreme Court and Court of Appeals, expecting they will rule in their favor if and when legal troubles arise. But FECI’s prosecutors have stood in the way.

Guatemala’s government has been criticized over the past year for driving out judges known for taking a hard line on corruption.

The removal of Sandoval—notorious for his dogged pursuit and prosecution of dozens of criminal networks, including those connected to former President of Guatemala Otto Pérez Molina (called for the legalization of drugs) and high-profile government ministers—prompted a domestic and international outcry. In August 2020, Porras removed FECI from a drug trafficking investigation related to the La Línea case, a much-heralded investigation that resulted in Pérez Molina’s and Baldetti’s resignation and arrest in 2015.

Sandoval’s case confirms fears that despite expressing a rhetorical commitment to fighting corruption, the Guatemalan state ultimately remains more interested and invested in defending entrenched traditions of elite impunity in the country.

Sandoval, however, highlighted irregularities in the complaints in an interview with news outlet La Hora. Most of these complaints were filed by current or former government officials, as well as other individuals. A complaint was also filed by Russian citizen Igor Bitkov, who was accused of buying counterfeit documents from a criminal network involving immigration officials. That case -which led to the conviction of 39 people, including both ex-government officials and the recipients of their illegal services — was later used as an argument to oust the United Nations-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala – CICIG), which worked alongside the FECI in its investigations.

Sandoval was likely to bet that the president’s team would not risk removing him from office, encouraged by Washington. If so, Giammattei’s decision might stem from two facts:

1. The President of Guatemala is under mafia’s thumb and fears for his life or

2. Giammattei has mobilized other support from outside the country, that, he believes, makes him feel it’s OK to break with the United States, giving up anti-corruption policy, as Russia or China are likely to rally behind.

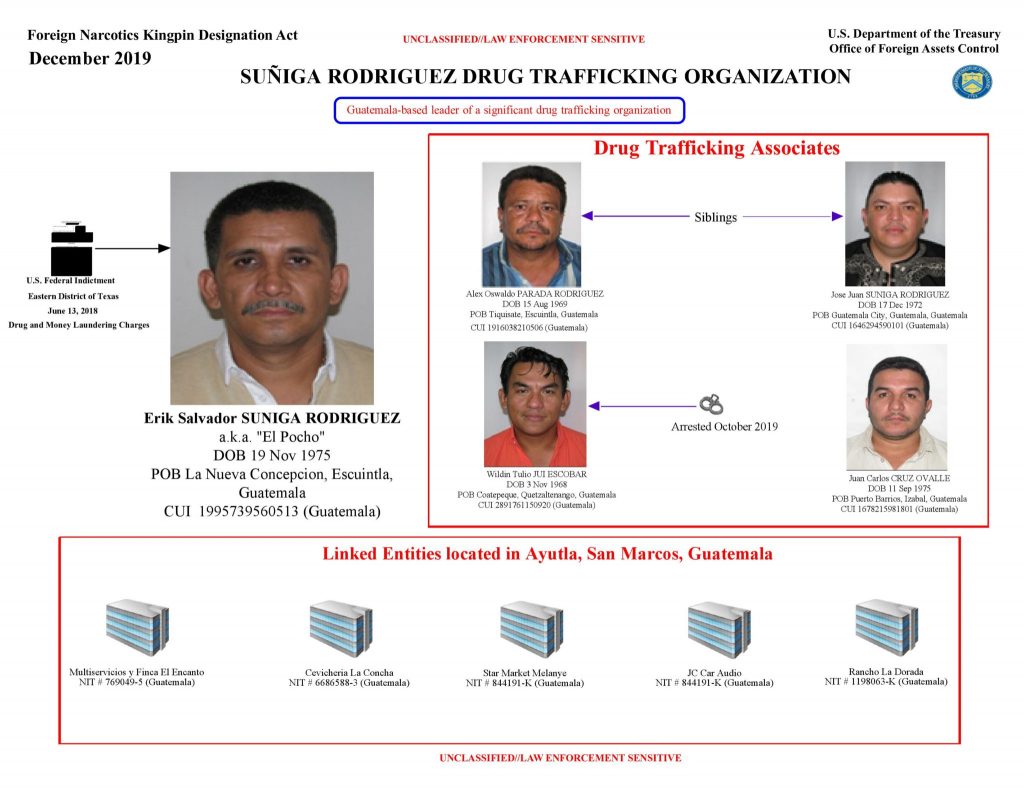

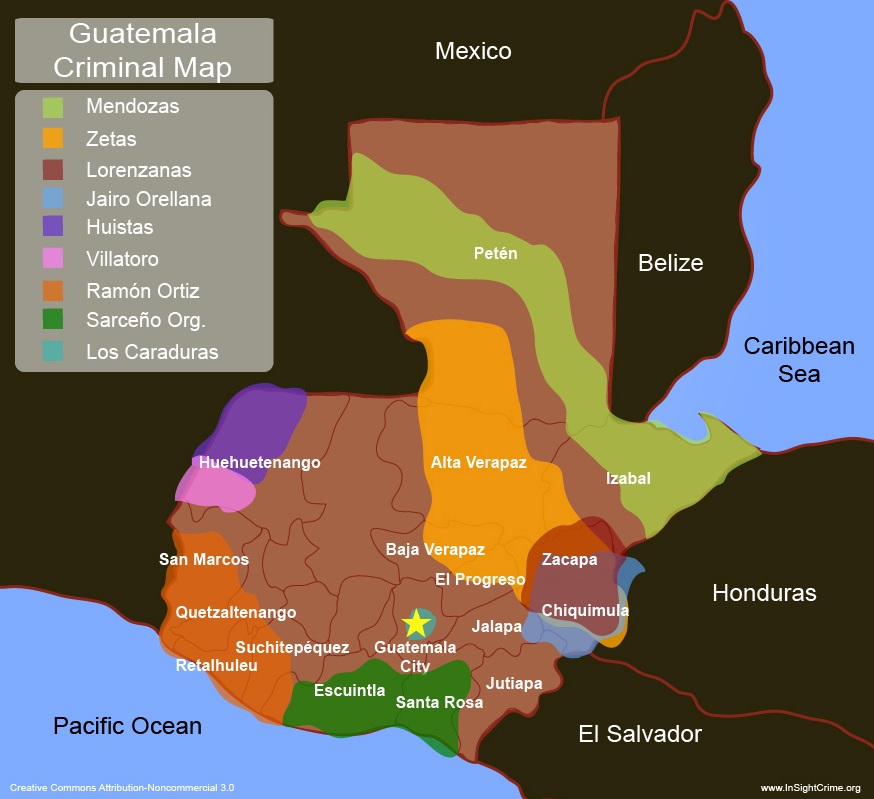

There are possible links between Mexican drug gangs and elected officials, including lawmakers in Guatemala’s Congress.

Guatemala has shown political turmoil starting last November, as protesters in Guatemala ransacked and set fire to the Congress building. People rioted then over cuts to education and health in the budget. They also accused the government of corruption and human rights abuses.

Fight against corruption is blocked by both active and former political groups in Guatemala.For example, the corruption investigations eventually reached all the way to former President Jimmy Morales, the country’s president between 2016 and 2020, and his family members. Morales launched a crusade to expel the CICIG and to shutter its investigations, which he finally achieved at the end of 2019. During his term, Morales named as Attorney General Consuelo Porras, who has since tried to debilitate the FECI, the prosecutor’s office that had worked hand-in-hand with the CICIG on high-impact cases.