Tensions between the Algeria and Morocco have been growing, and Algeria’s rhetoric points towards an armed conflict. However there are doubts that an escalation is imminent. Both countries don’t have any interest in waging a war on this conflict, so the most realistic scenario is that the bilateral relations are going to continue to stagnate.

Relations between Morocco and Algeria have deteriorated hit after three Algerian truck drivers were killed on Monday, November 8th. Morocco has denied any involvement in the bombings that took place in the Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara near the border with Mauritania. Morocco controls 80% of the Western Sahara, Algeria supports the independence movement Polisario Front.

But some early research suggests that the location where attacks took place is considered Moroccan by Rabat but under the control of the Polisario by Algiers. The killing of the three drivers on a desert road is the latest peak in a series of growing tensions between the two Maghreb states that support opposite sides of the dispute over the Western Sahara territory, a former Spanish colony.

On 13 November 2020, a ceasefire – that was concluded in 1991 between Morocco and the Polisario Front under the auspices of the UN – was broken after Moroccan troops were deployed to the far south of Western Sahara to dislodge pro-independence fighters that were blocking the only road to Mauritania, which – according to them – was illegal. The Polisario has since declared a state of war.

In November last year, then-US president Donald Trump had recognized Morocco’s claim over the phosphate-rich Western Sahara as part of an agreement for Rabat’s normalization of diplomatic relations with Israel.

It was much to Algeria’s dismay as it has been a firm supporter of the local Polisario Front with the Sahrawi group that seeks independence for the region.

Since then, relations between Algeria and Morocco have been going downhill with ambassadors being recalled, borders closed, accusations for sparking forest fires being thrown around, airspaces being blocked and the killing of three Algerian truck drivers adding fuel to the fire.

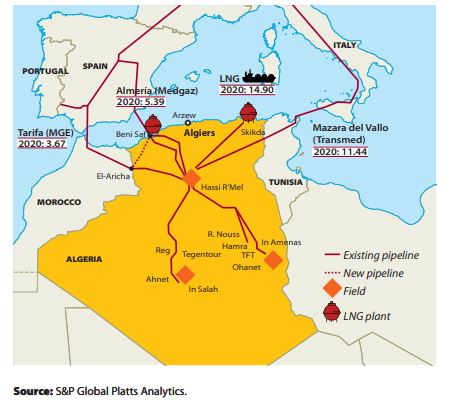

The two countries have a long history of tense relations, behind which lie issues of political ideology, border demarcation, and competition for regional influence. Morocco and Algeria fought a short border war after the latter’s independence from France in the fall of 1963, and Algeria has long supported the Polisario Front in its struggle against Morocco for control of the Western Sahara. The land border between the two countries has officially been closed since 1994, a decision Algeria made unilaterally following Moroccan accusations that the Algerian military was behind a terrorist attack in Marrakesh in 1994. The Moroccan leadership, including King Mohammed VI, has repeatedly called for re-opening the border, something Algerian leaders have consistently rejected. Still, the two countries have managed to find limited avenues for cooperation around a gas pipeline that transports Algerian gas through Morocco and on to Spain and other European markets, although the future of this arrangement is now in doubt.

The difficult situation has been even further exacerbated, with Algeria ending the contract for a gas pipeline that runs via Morocco to deliver gas to Spain. Tebboune had given the order to not renew the contract in light of the hostile behavior of the Moroccan kingdom. Algeria has been using the Gaz-Maghreb-Europe pipeline (GME) for the past 25 years to deliver natural gas to Spain and Portugal — via Morocco. Morocco, in turn, has been receiving about 10% of its gas supply as compensation. But the contract between Algeria’s state-owned energy company Sonatrach and the Moroccan National Office for Energy and Potable Water (ONEE) ended without renewal in late October this year. While Algeria has promised to meet Spain’s demand by using the smaller undersea Medgaz-pipeline instead — as it doesn’t run through Morocco — the decision has sparked fear of gas shortages and soaring energy prices in Spain and other European countries. For Algeria, much is also at stake if they can’t meet the demand. Algeria can replace the supplies to Spain through the Medgaz pipeline. There are expansion plans for that, but they’re not due for completion until the end of this year.

The 10% cut of energy supply is a setback for Morocco as well, since the country has to import about 95% of its energy. Solar panel initiatives are already running but Morocco is far from being energy-sufficient enough to cover such a loss.

According to Morocco’s ONEE statement, the decision announced by the Algerian authorities not to renew the agreement on the Maghreb-Europe gas pipeline will currently have only a minimal impact on the performance of the national electricity system.

The Moroccan King Mohammed VI. can rely on a broad social and political consensus that the Western Sahara should be Moroccan and he has little criticism to fear from his own people. A former Spanish colony with extensive phosphate reserves and rich Atlantic fishing grounds, the Western Sahara is seen by Morocco as its own sovereign territory.

Morocco has been keen on mending ties with various European countries, among them Germany, after several fallouts in the past year.

Morocco is in a difficult position because it needs to repair its relationship with the EU at the moment, and particularly now it wants to complete that process so it can focus its diplomatic efforts on the situation with Algeria. But it doesn’t have the capability to handle both issues at the same time. Despite Tebboune has been upfront that his country would go to war with Morocco, the armed conflict at the moment is unlikely. Neither side can really afford to push the conflict too far.