Expansion of the Solomon Islands by China encourages civil unrest in the region, leads to violence, as separatist movements emerge full blown.

Riots rock the Pacific Solomon Islands for a second day. The protestors who disagree with the policy of the government and Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare, have set fire to the parliament building and looted stores in capital’s downtown area. The protestors want to bring down the “democratically elected government”, Sogavare said. Australia’s police officers are heading to the islands.

Discontent has simmered for decades between the two islands, mainly over a perceived unequal distribution of resources and a lack of economic support that has left Malaita one of the least-developed provinces in the island nation.

Many of the protesters had traveled from the island of Malaita to Guadalcanal Island, which houses the nation’s capital.

Malaita is the most populous of the islands, with residents numbering 160,500 as of last year. Densely forested, mountainous and volcanic, it lies 30 miles northeast of Guadalcanal, the larger island, across Indispensable Strait.

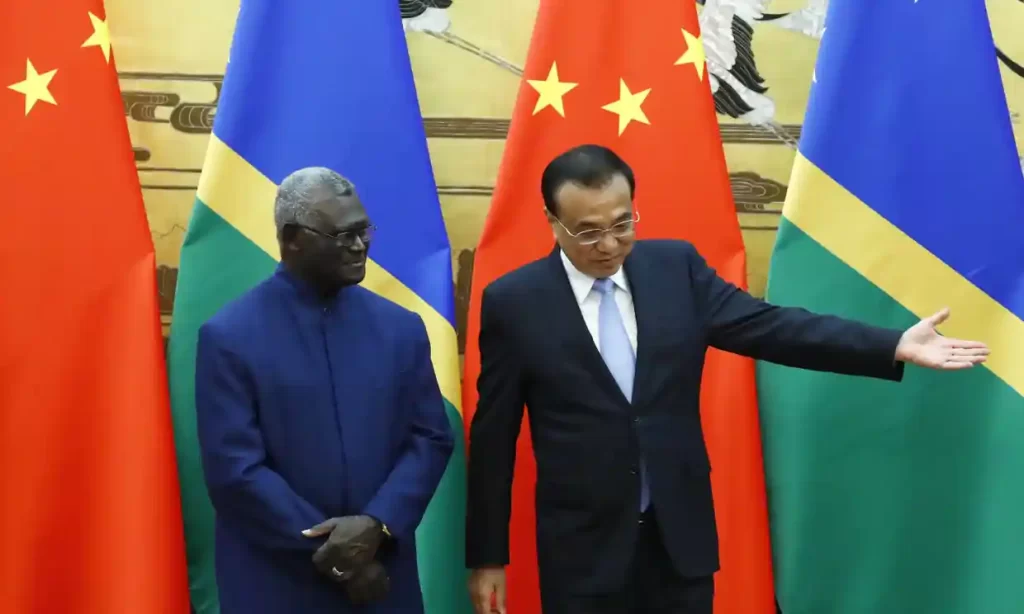

There has also been lingering dissatisfaction in Malaita over the central government’s decision in 2019 to switch diplomatic allegiances to Beijing from Taipei, Taiwan, a self-governing island that China claims as its territory.

In 2019, a Chinese company signed an agreement to lease one of the islands, but the agreement was subsequently ruled illegal by the attorney general of the Solomon Islands.

Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs accused Beijing of bribing Solomons politicians to abandon Taipei in the run-up to the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China under the Communist Party.

The United States sees the Solomon Islands, and other Pacific nations, as crucial in preventing China from asserting influence in the region. The United States provides Malaita with direct foreign aid while China supports the central government.

Malaita’s premier, Daniel Suidani, has been a vocal critic of that decision by the prime minister, and Malaita continues to maintain a relationship with and receive support from Taiwan — in contravention to the central government’s position. Suidani’s stance enjoyed popular support and attracted the backing of the micro-nationalist Malaita for Democracy (M4D) movement, which has linked its support for the premier to a demand for Malaitan independence.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Suidani has even maintained an informal diplomatic relationship with Taiwan, which has delivered Malaita consignments of COVID-19 equipment, angering both China and the Sogavare Government.

In 2020, Malaita has announced plans for an independence referendum as tensions with the country’s national government over China policy rise. The referendum plan comes after a year of tensions between Suidani’s provincial government, which is supportive of Taiwan, and Solomon Islands’ national government which has adopted a pro-Beijing stance. Malaitans protested against the national government’s decision at the time, citing China’s animus towards Christians and an undemocratic political system.

The last year unrest in Malaita is being followed closely by Taiwanese diplomats formerly stationed in Honiara, who were forced to leave Solomon Islands when Honiara switched to Beijing.

World War II attracted many Malaitans, whose agricultural land was overpopulated, to move to Guadalcanal to work for the US military; many stayed and more followed in the post-war decades. Subsequent British colonial policy increased incentives to stay by concentrating infrastructure investment where the export investment opportunities were—mainly Guadalcanal, but also Western Province. Malaita, by far the most populous province, was neglected by all forms of private and public investment, sometimes because of the obstacles Malaitan landowners put in the way of investors. So, increasing numbers of hardworking Malaitans moved to the opportunities in Honiara and environs (Guadalcanal), as well as to commercial nodes such as Gizo (Western Province). The problem was not only slow development, but resentment over uneven development. The people of Guadalcanal came to view Malaitans as disrespectful guests on their land. One of the Guadalcanal militia commanders, George Gray, explained the importance of this disrespect as a grievance that led to violence.

Many Guadalcanal people (predominantly males) from areas around Honiara were selling customary land to those from other provinces, even though Guadalcanal is a matrilineal society where females are regarded as the custodians of land. Many individuals were selling land without consulting other members of their line, often causing arguments among landowners. The sale of land has, over the years, been resented by a younger generation of Guadalcanal people who view the act as a sale of their ‘birth right ‘. When Guale militants started evicting Malaitans from Guadalcanal, Malaitans sometimes viewed this as uncompensated eviction from lands they had paid to share, while the militants saw it as termination of invitations to the Malaitans to be guests on their land. Young people rebelled against elders who took money for land that they did not own in any continuing sense because in much of Solomon Islands people do not own land, but rather the land owns people who are there to take care of it.

Inter-island tensions spurred civil conflict between militias on the two main islands from 1998 to 2003, during a period known as “the tensions.”

In a conflict more about national unity than secession, Guadalcanal forces sought to expel Malaitans living in and around Honiara. They were met by Malaita militia protecting the right of its kinfolk to live securely in a single united country.

There were two major stages to the conflict. The first was an indigenous uprising initially among young men from the impoverished Weather Coast region of Guadalcanal, with the active involvement of political leaders such as Guadalcanal Premier, Ezekiel Alebua. That was the insurgency by the Isatabu Freedom Movement (IFM), previously called the Guadalcanal Revolutionary Army. Its leaders had the objective of driving settlers from Malaita off the island of Guadalcanal.

Late in 1999, the second phase began with the creation of the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF), initially to defend Malaitan interests against the Guale rebels—something the government of Bart Ulufa’alu appeared to be incapable of doing. In a joint operation with the Malaitan-dominated paramilitary wing of the Royal Solomon Islands Police, the MEF effectively staged a coup that resulted in the coerced resignation of the incumbent prime minister on June 5, 2000.

The most arms were not surrendered, and the two militias splintered into a variety of armed criminal groups who indulged in banditry, intimidation and payback amid growing impunity facilitated by the effective collapse of the police force.

The pandemic is now entangling two significant sources of domestic tension: relations with the People’s Republic of China and micro-nationalism. The 2019 decision by Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare to reassess Solomon Islands’ relationships with Beijing and Taipei has been controversial among those concerned about the geopolitical consequences while stirring up significant domestic push-back.

Nevertheless, the chances of success for the separatist movement seem low.

Neither Taipei nor Washington genuinely wants, or intends, to foment destabilisation in the Solomons. Canberra and Wellington are scarcely in the mood for a repeat of the 13-year intervention under the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands that ended the civil war and sought to rebuild the country.