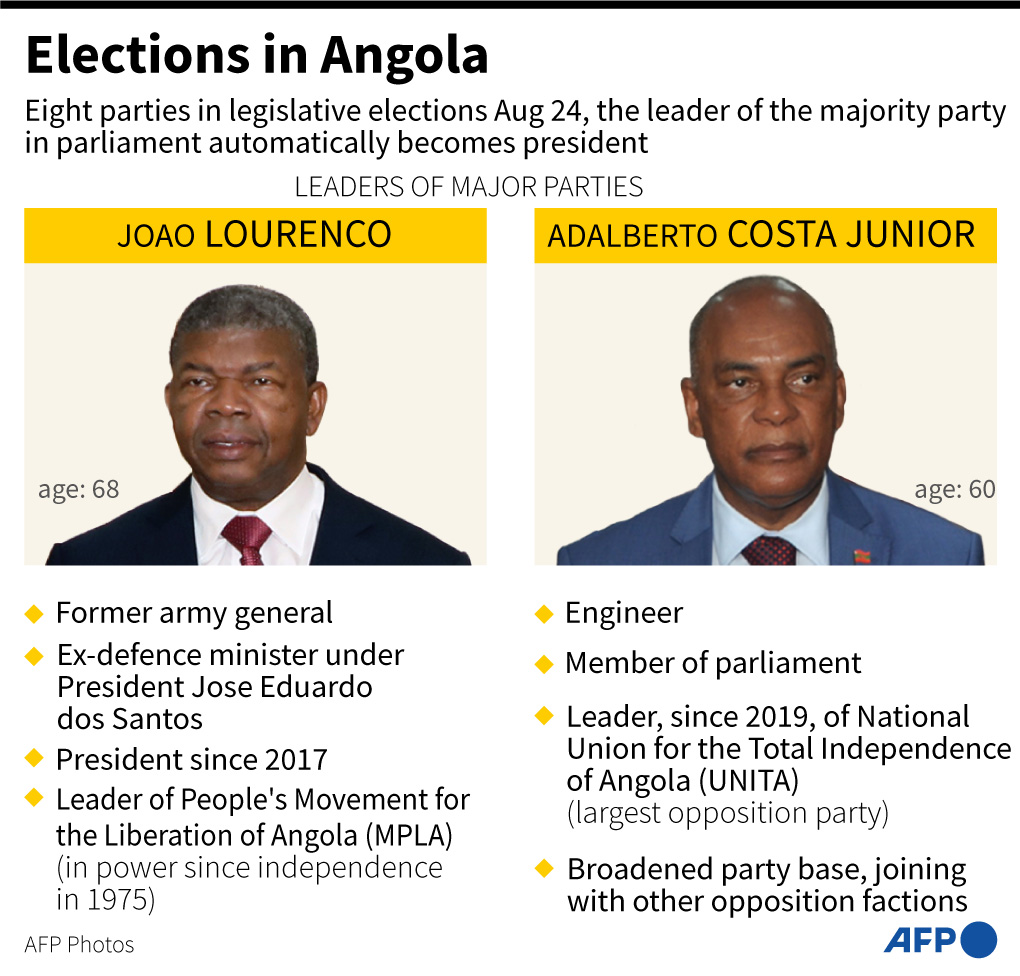

A close race between incumbent Angolan President Joao Lourenco and opposition leader Adalberto Costa Junior is a likely result of presidential race. Mass rigging could be a trigger for violence in Angola after general elections of August 24.

There are deep concerns about whether the vote will be free and fair. In 2021, MPLA used its super-majority in parliament to pass legislation that centralized the counting of votes—moves that critics say were designed to undermine the integrity and transparency of this elections.

According to Angola’s constitution, the leader of the faction with the most parliamentary seats will automatically be elected president of the republic.

This will be the fourth election since the end of the Angolan civil war in 2002. The three previous post-war polls were marked by a steady decline in the number of people voting for the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). In the last election, five years ago, the party’s share of the vote was down to 61% nationally, in contrast to 70% in the previous election according to the official tally.

Thus, these elections are expected to be the closest election since the country first allowed a multi-party vote in 1992. The key question is whether voters will once again pick the left-wing People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), which has run the country for half a century, or back the center-right National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) under the charismatic Adalberto Costa Júnior.

A high unemployment, corruption, and the repression of civil liberties has hit MPLA’s popularity, particularly among Angola’s disillusioned youth, for whom the memory of the civil war may not be as fresh. One of the main state-owned television channels, Televisão Pública de Angola, gives extensive coverage to the MPLA and almost none to opposition parties, while state-owned newspaper Jornal de Angola has consecutively featured Lourenço on its front page for almost two weeks.

MPLA’s struggles with younger voters are similar to the issues that other erstwhile liberation parties are grappling with across the continent, including the ANC in South Africa, SWAPO in Namibia, and FRELIMO in Mozambique.

In Angola’s five biggest cities, where the vast majority of Angolans live, the candidate of the largest opposition party, The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), is very popular.

About 14.3 million eligible voters have a choice between eight different political parties. At stake is the distribution of the 220 seats in the Angolan parliament and the question of which party can garner the most votes.

A high voter turnout is expected by the opposition coalition as the oil-rich Cabinda province will be a major battleground.

Corruption will be one of the main issues in people’s decision making.

The economy will be a also deciding factor in the vote, amid the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the government’s response.

The opposition accuses the MPLA of using state funds for its election campaign.

President Lourenco had made the fight against corruption a central issue in his first election campaign in 2017. He promised to introduce new compliance rules for state-owned companies, especially for the all-important oil industry. In addition, powerful ex-generals were targeted by the Angolan judiciary for corruption, and not even the relatives of his predecessor, the late President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, were spared.

During the election campaign, the main rivals accused each other of “cultivating relations with corrupt people.”The ruling MPLA implicitly accused UNITA of having its election campaign financed by the children of Eduardo dos Santos but provided no evidence for this allegation.

On the other hand, UNITA calls Lourenco’s anti-corruption measures “cosmetic” to achieve publicity, while the fight against graft continues to be neglected.

Of the eight candidates, only two — Joao Lourenco and Adalberto Costa Junior — have a chance of moving into the presidential palace in Luanda.

The most likely scenario is that the MPLA wins the elections by manipulating the electoral and judicial institutions. This could spark a popular uprising that could lead to post-election violence. According to the second, less likely scenario is a UNITA victory that could lead to some conservative groups within the MPLA refusing to transfer power. And only a transparent election process to prevent violence.

The 2022 election is the first in which citizens born after the war are old enough to vote. To this generation, the old slurs against Unita are meaningless. Even in traditional MPLA strongholds such as Malanje in north-central Angola, the party has battled to mobilise support at campaign rallies.

The 2017 election marked the resignation of President José Eduardo dos Santos, who had been in office since 1979. Incumbent Lourenco, 68, became involved with his party as a youth and worked his way up. He was in the MPLA’s politburo for many years, became governor of several inland provinces, and later defense minister.

Lourenço was elected in 2017 and promised more transparency, less corruption and inclusive governance. But as his first term ends, his time in office has been as authoritarian and highly criticised as that of his predecessor.

In 2017, Jose Eduardo dos Santos chose him as his successor. Lourenço put substantial effort into holding the dos Santos family to account. But Lourenço also faced criticism for tackling corruption in a selective manner.

During the 2022 election campaign, he strictly refused to participate in debates, even with his rival from the UNITA party.

As the MPLA’s political capital has diminished, so the opposition has begun to look more credible. Unita, the main opposition party, began to broaden its social base during the 2010s, finding common cause with civil society and a growing protest movement particularly in Luanda – a city where for previous generations, voting for Unita would have been anathema.

Most worryingly for the ruling party, it came in with less than 50% of the vote in the capital, Luanda, a city that it historically regarded as a heartland.