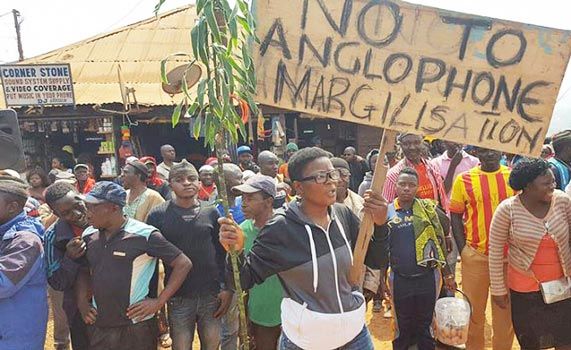

What began as a political dispute in the Anglophone regions is now a complex armed conflict and a major humanitarian crisis that disproportionately affects the civilian population, particularly women and children. The targeting of individuals based upon their cultural identity poses a direct threat to Anglophone and Francophone civilians and may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity. Longstanding tensions between herding and farming communities in the south-west and north-west regions have been exacerbated by the Anglophone conflict and the proliferation of arms. Patterns of deadly inter-communal violence between these groups leaves populations at further risk. Cameroonian government has decided to solve the historical problem militarily, denying the severity of the crisis and has failed to address the root causes of the conflict or engage in a political process to resolve it. However, The Cameroonian army has been repeatedly accused of abuses that have been denied by the Cameroonian government.

Cameroon’s government has deployed at least 100 troops to Gayama, a village on the border with Nigeria, after clashes between Cameroonian separatists and Nigerian herders left at least 12 people dead.

The fighting broke out after herders who crossed the border in search of food for their cattle refused to pay taxes the rebels demanded.

Abdoulahi Aliou, the highest-ranking government official in Menchum, the administrative unit in charge of Gayama, said the rebels killed two herders immediately upon their refusal to pay. The surviving herders, who are ethnic Fulani from Taraba and Benue states, returned home and organized a counterattack.

They attacked separatist camps, and killed at least four fighters. Six civilians, including the traditional ruler of Munkep village and his son, were also killed in the clashes.

Cameroon’s anglophone separatists have attacked Nigerians along the border more often.

In June 2022, villagers in western Akwaya town said armed men believed to be rebels carried out a series of attacks that killed at least 30 people, including five Nigerian merchants.

The separatists have been fighting since 2017 to carve out an English-speaking state from French-speaking majority Cameroon.

The Roman Catholic Church in Menchum says many civilians fled Gayama and neighboring villages to avoid getting caught in clashes between separatists and the arriving troops.

Separatists acknowledged they have been battling Nigerian herders, who they say should respect their orders.

The socio-political crisis that began in October 2016 in the Anglophone North- west and Southwest regions mutated into armed conflict at the end of 2017. Seven armed militias are currently in positions of strength in most rural areas. The security forces reacted slowly, but since mid-2018 have inflicted casualties on the separatists. They have not been able, however, to regain full control over rural areas nor prevent repeated separatist attacks in the towns.

Seven armed militias present on the ground have a total of between 2,000 and 4,000 combatants. They recruit mainly from the Anglophone community, but also among the security forces and include dozens of Nigerian mercenaries, who generally bring their own weapons and ammunition and are deployed as trainers or combatants. Some are former combatants or those out of work after agreements between the Nigerian government and political-military groups in the Niger Delta. Others are simply criminals who fled to Cross River state to escape the Delta Safe 1 Operation launched in 2016 by the Nigerian army to fight crime in the Delta. Dozens of Cameroonian police officers and soldiers, mostly officers, and retired or discharged soldiers have also joined the militias. Most militias have female combatants, some of whom are local leaders.

In 2018, the militias gradually took control of some rural and urban periphery areas. Since September 2018, they have had to adapt their deployments to security force offensives but, despite suffering losses, they retain a position of strength in most of these areas, maintaining roadblocks and security checkpoints. Many of these weapons were seized from the security forces, while others were acquired in Nigeria from paramilitary or criminal groups in the Delta.

Initially funded almost exclusively by the diaspora, the militias have become more autonomous. They carried out kidnappings for ransom, extorted shopkeepers and certain sectors of the population and imposed “taxes” on companies. This relative financial independence allows them to cut themselves free from political organisations in the diaspora. Ignoring orders to respect the rights of civilians, they commit abuses and are gradually alienating the residents. As the population becomes less cooperative, they have greater recourse to violence to ensure obedience.

Since mid-2018, the conflict in Anglophone regions has spread to Cameroon’s Francophone regions, increasing the risk of intercommunal conflict. In addition to the armed separatist groups, some pro-government self-defence militias, especially in Bakweri and Mbororo communities, and an unknown number of small criminal groups and semi-criminal/semi-separatist groups are active, including in the West region.

Within the governing elite, almost all the Francophone leaders advocate a military solution to the conflict, but senior Anglophones in government are more divided. Some fear they will lose their positions in the event of dialogue, which may lead to the emergence of a new Anglophone elite. Others are favourable to dialogue with the separatists. But they are careful to hide their views and sometimes even take intransigent positions for fear of arousing suspicion they may be sympathetic to the Anglophone cause.

Some senior officers in the security forces firmly believe in repression. But others feel that a more political approach, with emphasis on decentralisation or regionalism, should accompany the military response. Aware there can be no military victory, they nevertheless hope to contain the conflict and reduce the violence to a residual level, as in the Far North. Rather than seeking complete control over the Anglophone regions, they aim to maintain control over urban areas, the urban peripheries and “strategic” rural areas.

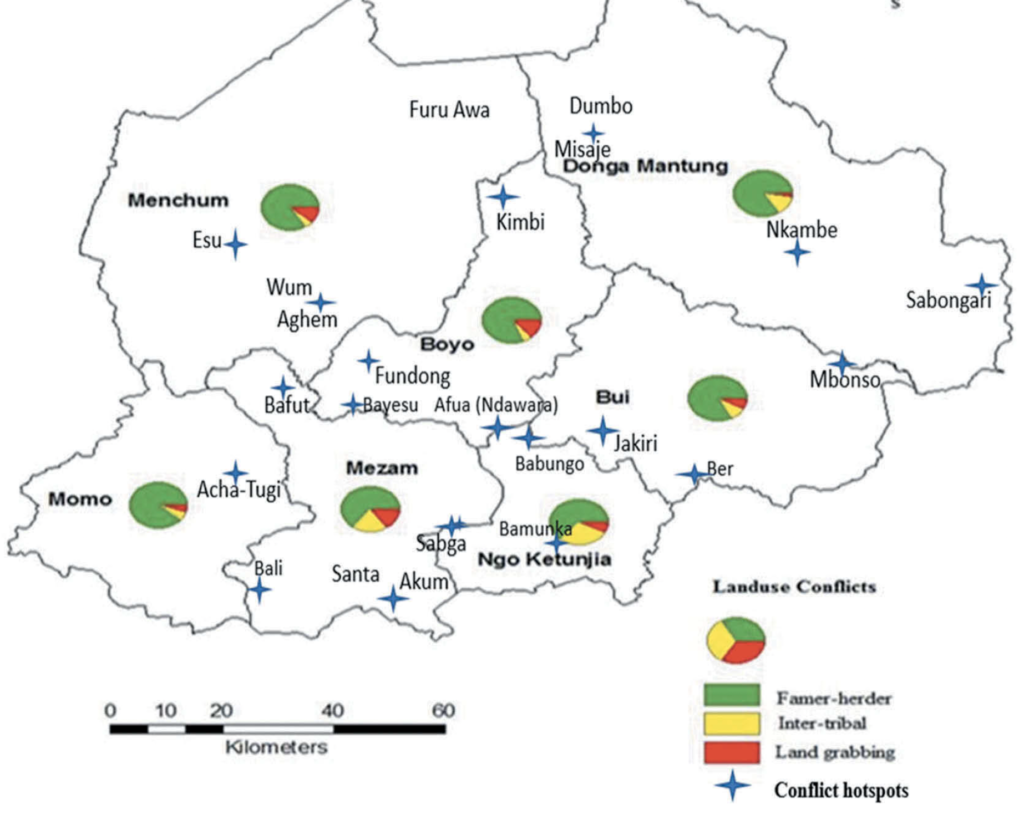

As a social conflict, farmer–herder conflict has been characterized by severe and persistent violence that create social tensions as well as human and environmental insecurity issues among rural dwellers across neighbourhoods’, often based on partial judgment or unresolved cases of crop damage by cattle or rangeland encroachment by farmers.Farmer–herder conflict is noted for its tendency of often creating suspicions and ethnic bias between local farmers and herders based on religious and ethnic differences. In recent years, such biases have escalated into open violence, becoming more deadly and socio-economically untenable across Sub-Saharan Africa, especially in Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Sudan, Niger, Senegal, Kenya, Burkina Faso, and Tanzania. In the Middle Belt of Nigeria, for example, farmer–herder conflict is responsible for more deaths than the Islamic terrorist groups of Boko Haram, Al Shabab, and Al-Qaeda combined. Farmer–herder conflicts in this region are deepened by Muslim–Christian divides, exacerbated by climate change, population growth, increasing threats of terrorism, and the availability of arms in the hands of herders, who aggravate hostilities and manipulate ethnic and religious differences across the Sahelian zone in regions like the Lake Chad Basin, Nigerian Middle Belt, and Horn of Africa.

Gun trafficking only increases violence and farmer–herder conflicts in the region.

Using a political ecological approach in analyzing the politics of farmer–herder conflicts and

alternative conflict management (ACM) in Northwest Cameroon (NWC) it becomes obvious that environmental change, scarcity, and insecure access to food, farming, and grazing resources, often driven by climate change and population growth are not always the main drivers of farmer–herder conflicts.

The term ‘farmer–herder conflicts’ in this usually refers to competition over agro-pastoral

resources in an ethnically and culturally heterogeneous environment between local farmers and

Fulani herders.

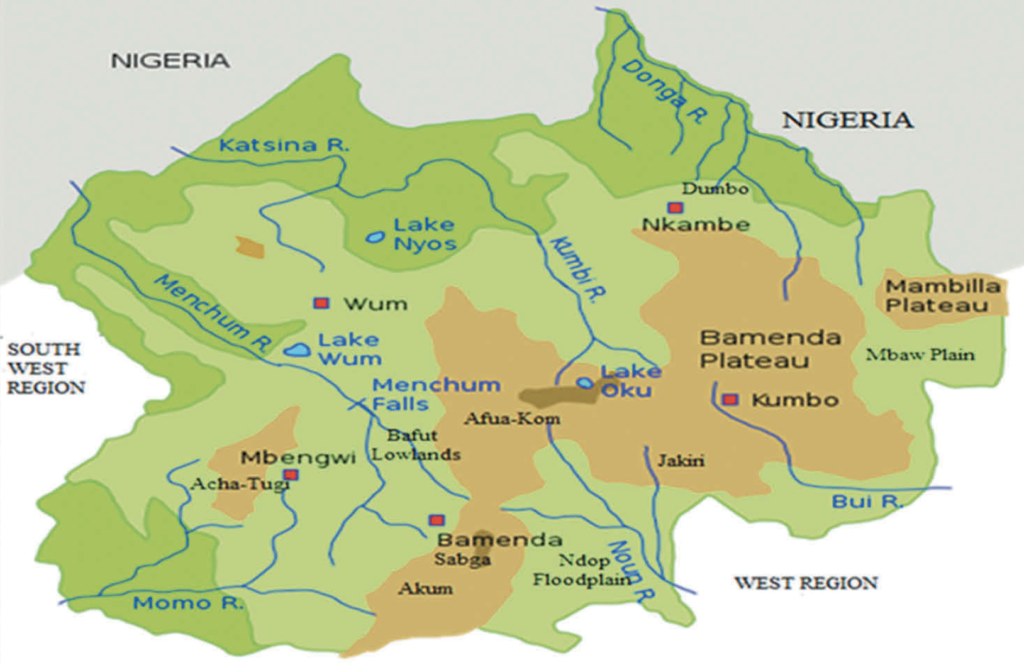

The politics of farmer–herder conflicts in NWC could be traced as far back to the British colonial period in Southern Cameroon in the 1920s and 1930s, which coincided with the early arrival of the first Fulani pastoral migratory waves into the territory. Early in their arrival, Fulani herders were mainly nomads, whereas the host farming communities

were farmers, hunters, and gatherers. Over time, Fulani pastoralists became sedentarized and seminomadic, encouraged by the British colonial administration; they realized growth in cattle numbers while also increasing crop damage by trespassing cattle in the Bamenda Grassfields.

The colonial administration wanted Fulani herders to become sedentary and diversify their production system by involving crop cultivation alongside

cattle breeding for subsistence, as well as reduce crop damage by cattle. The main objective of the British colonial administration in encouraging Fulani herders to settle permanently and only engage in transhumance was to increase the cattle tax revenue and Fulani population needed to augment the colonial revenue for the running of colonial affairs. This economic interest of the colonial administration led to the development of agro-pastoral policies that favored Fulani herders, such as the issuing of protected status with land certificates referred to as Certificates of Occupancy for Fulani settlements. Fulani herders took the certificate of occupancy as land rights and abused it by allowing their cattle to destroy crops belonging to local farmers around rangelands.Thus, the colonial government could only grant Fulani pastoralists in Southern Cameroon temporary protective status and not citizenship because it saw the latter as ‘strangers’. Local farmers and chiefs saw Fulani herders as intruders because of the growing incidence of crop damage caused by their cattle.