12 years after the start of the civil war in Syria, the country is facing a regional humanitarian crisis where over 13 million people, according to UN data, need help.

The Syrian massacre began on March 6, 2011 when fifteen teenagers were arrested for writing anti-government graffiti on the walls of a school in the city of Dara’a.

The barbaric punishment of the teenage boys became the catalyst for the mobilization of the people.

From a peaceful protest demanding political freedom and the end of corruption, it would turn violent as the days passed. Several protesters were killed by security forces during the demonstrations, marking the escalation of violence.

Faced with the murders, arrests and imprisonment that would result in the death and disappearance of thousands of people, one of the moves of the regime of Bashar al-Assad to gain allies within the territory would be to grant citizenship to about 120,000 stateless Kurds in Syria, who had remained without this right after the population census conducted in 1962.

Within a few months, the demonstrations turned into an armed conflict. It would be the political opposition created against the regime, several different ethnic and religious factions, Kurdish groups and Sunni Islamist jihadists to join the panorama of the conflict. Assad’s release of radical elements from prison would send them directly into the ranks of jihadist groups on the ground.

The conflict would soon attract different countries on the ground. In the face of the massacres, some of the Arab countries and Türkiye would support the Syrian opposition with the support of Western countries.

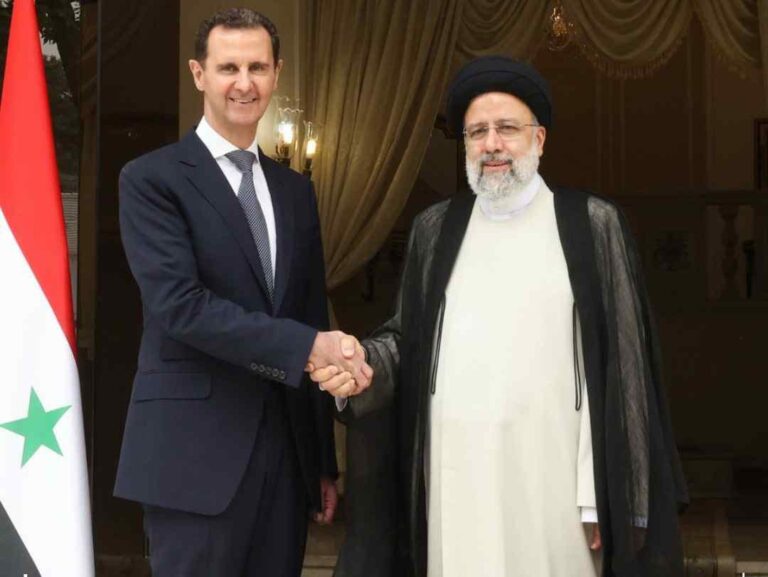

The Syrian President, Bashar al Assad, immediately had the help of the Iranian forces and those of the Lebanese Hezbollah.

The international community tried to resolve the conflict through diplomatic contacts, but difficulties, divisions within the Syrian opposition and disagreements between other parties, as well as the Syrian regime’s determination not to reach any agreement made any attempt impossible.

Very quickly, the fight against terrorism, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the al-Nusra group would return to the priority of the international community, dwarfing any attempt to replace President Bashar al-Assad.

This was the first achievement at the international level by Bashar al-Assad, after cutting off diplomatic relations with Western and Arab countries, as well as the exclusion from the Arab League.

The second step for Bashar al-Assad would be the final victory over all Islamist and secular opposition groups and regaining control of the territory. For this, in September 2015, Russia’s military intervention in Syria against ISIS came to his aid.

The forces of the regime with those of Iran and Hezbollah on the ground and the air attacks of Russia without discrimination against the Syrian civilian population, schools, hospitals, houses in the territories controlled by the rebels, would mark the turning point in favor of the regime of the President Bashar al-Assad.

The massacre of Aleppo at the end of 2016, after using the chemical weapons against the population, marked the defeat of the Syrian revolution and the victory of the regime.

Syria thus turned into one of the largest humanitarian crises with more than 13 million people having fled the country and 6.9 million internally displaced.

Undoubtedly, such a humanitarian situation could not leave untouched the neighboring countries such as Türkiye, which hosted over 3.7 million Syrians, Lebanon and Jordan, which also had the highest number per capita globally.

According to the report of the UN Security Council after 12 years of conflict “15.3 million people – almost 70 percent of the population of Syria – are in need of humanitarian assistance”.

Among the 6.5 million children living in Syria today, more than 2 million are currently out of school, 40% of whom are girls at risk of child marriage.

The conflict in Syria is currently at an impasse with little prospect of a political solution anytime soon. The Assad regime remains entrenched in power, controlling more than 60% of the Syrian territory.

Efforts to negotiate a political solution to the conflict as envisaged by UN Security Council Resolution 2254 have stalled.

The levels of violence, although with a completely different intensity from the peak of the first years, continue to see small-scale skirmishes along the conflict lines in northwestern and northeastern Syria.

Still, according to the SC report to the UN “the picture remains equally dire”, noting that shelling, rockets and intermittent clashes have continued along all conflict lines involving a wide spectrum of actors.

More broadly, the Syrian civil war has evolved into an internal conflict with diverse and internationalized actors, with five foreign militaries—Russia, Iran, Türkiye, Israel, and the United States—involved in the Syrian battlespace, as well as the remnants of of ISIS, which are still active and carry out continuous attacks against both soldiers and civilians.

The Syrian regime, the strongest internal actor, headed by President Bashar al-Assad somehow needs to have contact with the High Negotiations Committee (HNC), which represents a wide range of opposition groups, the Syrian Democratic Council ( SDC), which acts on behalf of the PKK-affiliated Kurds and very few Arab groups in northern Syria, as well as the International Syria Support Group (ISSG), which is made up of all major external actors in conflict.

Precisely at this stage, Bashar al-Assad’s regime seems to be achieving another success.

The February earthquake of this year undoubtedly deepened the Syrian humanitarian crisis, but it also opened new paths for al Assad, who demanded the lifting of sanctions in exchange for allowing the introduction of aid for the population affected by the earthquake.

These sanctions have never prevented aid from flowing to Damascus through UN agencies and being partially diverted from the regime. However, he won this too. The United States and the European Union have suspended, for six months, the sanctions imposed on the Syrian regime.

Also, the earthquake seems to have accelerated the normalization of Syria’s relations with other Arab countries.

Governments in the region have launched normalization efforts with the Assad regime since 2018, when the United Arab Emirates decided to reopen its embassy in Damascus.

Several other countries in the region, including Egypt, Jordan, Bahrain and Oman, have also taken steps to open diplomatic missions.

But after the earthquake, the Foreign Ministers from Egypt, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates visited Damascus. Most notably, Saudi Arabia sent aid to the Syrian government, with a Saudi plane landing in Aleppo for the first time since 2011. The Saudi foreign minister has also hinted that Syria could be readmitted to the Arab League, though there is a division regarding this between different countries.

Faced with this accelerated normalization with the Arab countries, what is the future of the conflict in Syria?

The state of the conflict in Syria at this moment can very well be said to be in a frozen state, with clear diplomatic successes as far as President al-Assad is concerned. This only strengthens it and does not make it at all ready to consider institutional reforms that may satisfy some of the local actors.

In addition to the misery, the destruction, the need for humanitarian aid and reconstruction, Syria is at the crossroads of the interests of neighboring countries.

Without a doubt the actors are clearly in action. Saudi Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman, wants to demonstrate to other Arab countries in the Middle East his role as a diplomatic mediator. And so it pushes the entire League to an autonomous and stronger position in front of the big blocs that compete in the Syrian scenario.

Iran and Russia are undoubtedly Assad’s strong allies who have no intention of moving after a successful involvement. For them, Syria is a regional strategic interest. But it is not yet known what the consequences of Chinese activism will be regarding the two aforementioned actors.

Without a doubt, a possible Sunni Syria linked to the Arab countries would endanger the role of Iran. Therefore, keeping Assad in any dialogue for the future is of vital importance for the Islamic Republic.

For Russia, Syria is important because of its military presence in the Mediterranean through the port of Tartus. So if President Bashar al-Assad leaves without a mutually accepted successor, Syria risks becoming a failed state, and it is a risk that Russia will try to avoid.

Türkiye, which shares a 911 km border with Syria, will continue to protect its strategic interests. Ankara will continue to fight the forces of the Islamic State. But although it supports efforts to find a peaceful solution to the Syrian conflict, it would oppose any effort that would involve the PYD and/or the SDC in a dialogue about the future Syrian political solution.

Israel, for its part, will keep under constant control the Iranian forces and those of the Lebanese Hezbollah on the ground. It cannot risk the deployment of various weapons to Lebanon. This is the reason for frequent bombings against military targets in Syria. Intervention that requires tacit cooperation with Russia, which controls Syrian airspace.

As far as the United States and the West are concerned, the rehabilitation of Bashar al Assad by the Arab countries clearly becomes an indicator of how much the American order has eroded in a multipolar environment.

The United States and the United Kingdom are continuing on their path of imposing sanctions on families or entities associated with President al-Assad, specifically for the production and trafficking of the drug Captagon.

But just like since the beginning of the conflict in Syria, a comprehensive strategy is missing.

Meanwhile, efforts to address the abuses of the Syrian regime through European courts have yielded a still very small result. Last year a German court convicted a former Syrian intelligence officer of crimes against humanity, sentencing him to life in prison for his role in torturing and killing prisoners in a prison in Damascus.

Also, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres in a report last August recommended the creation of an entity that would strengthen efforts to address the issue of the missing and detained in Syria, about which nothing is known. But concrete results have not yet been seen.

The return of the president-dictator accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity undermines the entire system of rights and sanctions that the West has built since World War II until the indictment of Vladimir Putin for war crimes in connection with the deportation of Ukrainian children.

What credibility would remain in our world based on human rights, if tyrants, dictators accused of war crimes, can abuse their people and find themselves legitimized, only ten years later?Hope is the last to die, in this case at least the hope is the West to not forget its principles.