Protests are possible across Thailand through at least late June following a probe into prime minister front runner Pita Limjaroenrat from the opposition Move Forward Party.

According to local reports, the Election Commission will investigate if Pita violated an election rule prohibiting candidates from holding shares in a media company. The decision comes after the Election Commission dismissed three previously filed complaints against Pita on June 9.

Clashes between protesters and police are possible.

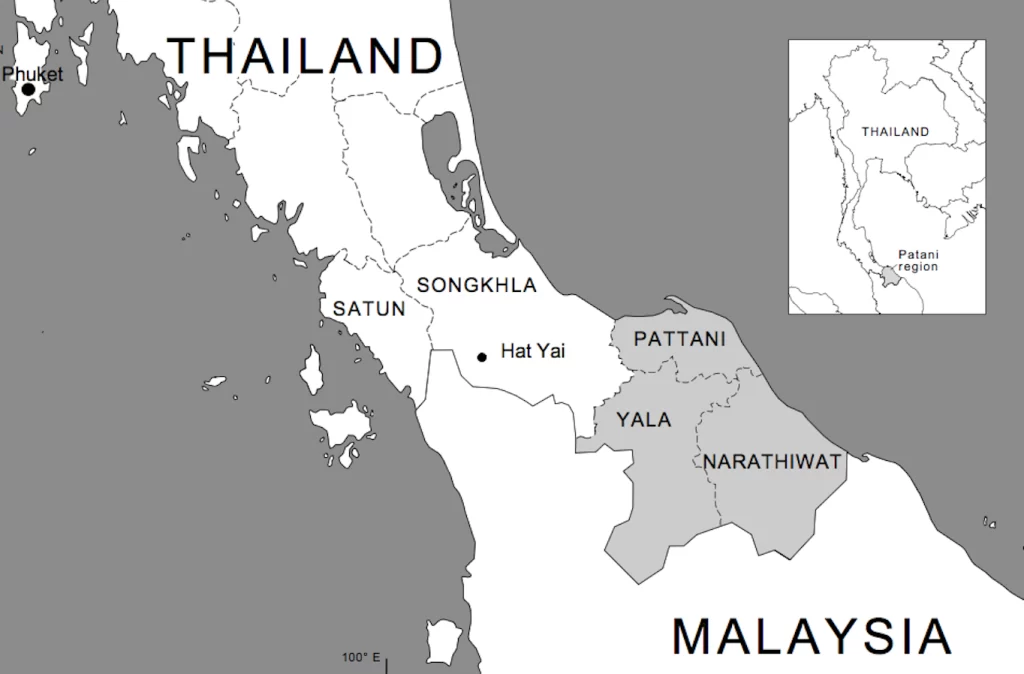

Thailand’s government is investigating activists for allegedly talking about Independence for the Pattani region.

The National Security Council of Thailand has launched an investigation into the activist group that calls for referendum and separate Muslim state in the country’s south.

Group activities are currently being studied, with many activists under surveillance. If the group is recognized as a separatist movement, the participants may face criminal punishment, as calls for separation violate the constitution and other laws.

There is still no solid answer whether a certain political force is behind the group.

The investigation focused on a recently created activist group, the National Students, representing three Thailand’s southernmost regions.

The group is the latest incarnation of the Federation of Patani Students and Youth (PerMas), which was disbanded in November 2021.

Some political figures and MPs – Worawit Baru, deputy leader of the Prachachat Party and MP-elect for Pattani, and Hakim Pongtigor, deputy secretary-general of the FAIR Party, were spotted at one of the group’s meetings.

A bomb blast in the Bannang Sata district of Yala province in Southern Thailand on May 12, just two days before the country’s general election, is a telling tale of how deeply trapped the region is in insurgency and violence. The explosion claimed an army ranger’s life while three ranger volunteers were also wounded.

Scholars and observers of the Southern Thailand conflict have been warning about this for the past several months. They said that the violence in insurgency-hit Southern Thailand was primed to escalate, noting that it registered an upward trend even in 2022.

The insurgency has been sustained by local groups over the last 15 years without outside assistance. They have not succumbed to outside forces or doctrines along ‘globalist Jihadi’ lines, as other region insurgencies have. Insurgent narratives have remained clearly based upon local Malay-nationalist issues.

The roots of the separatist insurgency in southern Thailand can be traced back to 1785, when the Patani Sultanate became a part of the Kingdom of Siam. Later, in 1909, with the signing of the Anglo-Siamese Treaty, the borders between Thailand and Malaysia were fixed in their current location. This left the historical Patani region, which consists of the present-day provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala along with four districts in neighboring Songkhla, inside the borders of Siam. These Muslim-majority regions have been the locus of a separatist movement since 1948. Subsequently, numerous ethnic Malay-Muslim insurgent organizations emerged demanding separation from the Thai government. The most prominent ones include BRN (Barisan Revolusi Nasional), RKK (Runda Kumpulan Kecil), GMIP (Pattani Islamic Mujahideen Movement), BIPP (Islamic Liberation Front of Patani), and PULO (Patani United Liberation Organization).

Commentators on the region suggest that the Thai Government’s repeated attempts to assimilate the region in the period 1902-1944, and again in the 1960s and 1980s played an important role in arousing Malay-nationalistic awareness. More recently, the Krue Se Mosque and Tak Bai incidents in 2004 enraged emotions against the Bangkok government, which led to the escalation of violence to what it is today.

A number of insurgent groups are involved. These include the Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN), which has been primarily interested in cultural and Patani-nationalist goals. Another group primarily composed of much younger Salafi followers, the Runda Kumpulan Kecil (RKK), is much more militant, and believed to be either a breakaway or operational group from the BRN. Others include the Gerakan Mujahidin Islam Patani (GMIP) and the Barisan Bersatu Mujahidin Patani (BBMP). Pioneering groups like the Patani Liberation Organization (PULO) have not been as active on the ground over the last decade. There are almost a dozen other small and fragmented groups.

Insurgents have almost an unlimited choice of targets to select and tend to attack the easy ones. Recently attacks on unprotected targets outside the region have disrupted tourism and gained international media attention.

Most attacks are carried out by small closely knit and independent cells, who don’t communicate with anyone outside their respective groups. They blend in with their respective communities and thus it is extremely difficult to identify cell members.

For predominantly Buddhist Thailand, Muslim-Malay claims that the Thai government and society have attempted to violate their cultural and religious identity by pushing a national assimilation agenda, seems a far-fetched narrative, especially in the context of the state of minorities in other Southeast Asian countries, including Malaysia. That said, a feeling of relative deprivation seems justified considering that Southern Thailand remains the most underdeveloped part of Thailand. The region is a mix of Chinese, Malay, and Thai ethnic groups. The Deep South is the only place in Thailand where another ethnic group, Malays, outnumber the Thais.

While political leaders and interlocutors often deny it, the problem has an ethnic dimension as well. The majority Malay-Muslims of Southern Thailand, Thai Buddhists, and other Thai ethnic groups rarely interact socially due to several inter-societal and inter-community differences. It has been challenging for Malay-Muslims to assimilate into the political and religious culture of the Thai state, and Islamic beliefs and practices diverge from the state’s focus on “nation, religion (i.e. Buddhism), and king.” For the Thai authorities, the Muslim-Malay community has been somewhat impenetrable in a fragile law and order situation – a deadly mix that has worsened the conflict and held back the region’s economic development.

Malay culture itself is slowly becoming influenced by Salafi ideas. It’s not the same straightforward Malay culture it was a generation ago. This cultural shift is opening up the potential for new catalytic narratives to be viewed sympathetically in the future, as some radical narratives are in Malaysia.

Given close ties between these communities, there is some danger that these narratives will be seen as solutions for the younger generation, who think very differently from the older generation. They may not show popular support for Patani-Nationalistic ideals, as the older generation did. However, if these new narratives take hold, then the current conflict will become much more complex.

Last year’s increase in bloodshed in Southern Thailand may have been a sign that the rebels were growing impatient with the government’s fruitless efforts to broker a peace deal.

However, the large number of people in this historically contested region don’t want an independent state.

Attacks took place following talks between the Thai government and the largest insurgent organization, the BRN, that had been suspended for two years due to the COVID-19 pandemic and resumed in early 2022. However, in a decade of talks not much has been achieved.

Anti-government campaign rallies over the military and monarchy’s continued presence in Thai governance heated up as the country moved at noon of May 14 general election, which saw a victory for the progressive opposition Move Forward Party, which was planning to form a government and end nine years of military and military-backed rule under Prayut. The official results of Thailand’s May 14 general election are still pending, and the Election Commission must certify the results for 95 percent of constituencies by July 13. The Election Commission ordered a recount of ballots from 47 polling stations June 7 and is currently investigating over 280 cases of irregularities.

Thailand’s opposition Move Forward Party (MFP), which won the majority of votes in the recent general election, signed an agreement with seven other parties in May to form a coalition. The MFP is currently engaging in negotiations with senators to secure the remaining votes needed for the formation of a majority government.

While protest activity in the lead-up to and following voting day has generally remained low, the potential for small-scale demonstrations remains. Any military involvement or interference in the election process after the announcement of the official result could contribute to an escalation of public unrest. Additionally, separatist militants could stage attacks in Thailand’s restive Deep South region following the general election.

Negotiations have been taking place between the military and an umbrella body representing the insurgents, MARA Pattani (Majlis Syura Pattani). However, the results to date indicate that the peace negotiation process has failed. The military have been aiming for transactional results, such as declaring safety areas. However, the real issues behind the conflict have not been discussed.

Calls for a public referendum about the establishment of an independent Muslim state are not allowed under the constitution.

Lt Gen Santi Sakultanak, commander of the 4th Army, blasted the referendum proposal, calling it unconstitutional and a threat to Thailand’s territorial integrity and national security.

In addition to the insurgents, the violent situation in the Deep South is further complicated by unconnected criminal groups along the border region. Their vested interests are best served in a destabilized environment, where narcotics trade, smuggling, and other criminal activities can thrive. Little, if anything has been done by the police or military to curb this, so that these activities can be isolated from the insurgency.

The rural youth, unemployed, idle and using drugs is a major regional problem. This socially weak group is susceptible to influence, and a major source of recruits for the insurgency. Instances of poor treatment and even extra judicial attacks by police and military personnel have also been cited as a motivator to youths in this group to join the insurgency.