One of the most turbulent elections in Guatemala’s modern history is questioning democracy in this country. The Constitutional Court has intervened in the election system. Court’s decisions have undermined some voters’ trust in the electoral system.

Authorities actions seems to be attempts in to question the results of an election. The parties that didn’t make it to the second round or into Congress are worried there could be some policy changes that affect them.

Some of the most popular aspirants will be on the sidelines in voting because electoral authorities and courts blocked some from running and cancelled the candidacies of others who were initially allowed to enter the race. A week after Guatemala’s June 25 elections boosted a relative long-shot candidate into the final second round of voting, the country’s top court has frozen certification of the election results.

Several political parties filed appeals questioning the vote, and the court agreed to freeze certification of final tallies until those complaints can be reviewed. This decision could shift the results in lower-level contests, where the margins for victory were much tighter.

By the day after the elections, a preliminary count based on tallies reported by voting precincts was quickly added up, revealing the results. But those results must still be officialized by the country’s electoral court.

Ten of the 29 parties that ran candidates in the race filed complaints, alleging there were problems with the count they claim may have cost them votes. They filed for an injunction against officializing the results. But none of those parties won more than 8% of the vote.

There is no re-election in Guatemala, so President Alejandro Giammattei is not among the 22 permitted presidential candidates. Guatemalans will also elect all members of congress and hundreds of mayors across the country.

the center-right candidate and former first lady Sandra Torres of the National Hope Unity part came in first with 15.8% of the vote. She won the first round, but has alleged votes were manipulated.

Coming in second was left-of-center candidate Bernardo Arévalo from Seed Movement, whose father was president before Jacobo Arbenz, who was overthrown in a coup in 1954. Arévalo got 11.7% support. Opponents have blasted the party as “socialist” and “communist”. Torres has also accused her Seed Movement rival Arevalo of threatening to expropriate private property and end religious freedom in favour of an “LGBT ideology”. She has also sought to portray Arevalo as a “puppet” of foreign governments.

Arevalo says he’ll bring back anti-corruption judges and prosecutors in exile as advisers to help him develop his strategy.

Arevalo’s upset provoked complaints from 10 political parties, including the UNE. They argue a “great quantity” of the votes show “inconsistencies, alterations and other discrepancies”. At least six of the parties that issued complaints face cancellation after failing to obtain the minimum number of votes required to remain a legally recognised political party.

According to the electoral legislation, Guatemalans age 18 and older can vote in elections held every four years, and some 9.2 million are registered. More than half of them are women. Voting is not compulsory.

At polling places, voters will receive five ballots covering the various races in their districts.

In the presidential contest, the ballot will feature the faces of the presidential and vice presidential candidates on the 22 registered tickets. At least 50% of the votes are required to win outright. Otherwise, a second round pitting the top two finishers would be held Aug. 20.

Political parties must end their campaigns Friday, two days before the vote, and no opinion polls can be published after that.

The Supreme Electoral Tribunal enforces Guatemala’s electoral laws, but regular courts also have jurisdiction when parties ask them to get involved.

Earlier this year, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal ruled that Thelma Cabrera, an Indigenous farmworker leader, could not be a presidential candidate because of a paperwork issue with her running mate. In early May, the Constitutional Court rejected her leftist party’s final appeal.

Last month, Roberto Arzú, a conservative law-and-order candidate, lost his final appeal to get back into the race. The electoral tribunal annulled his candidacy for allegedly starting his campaign prematurely.

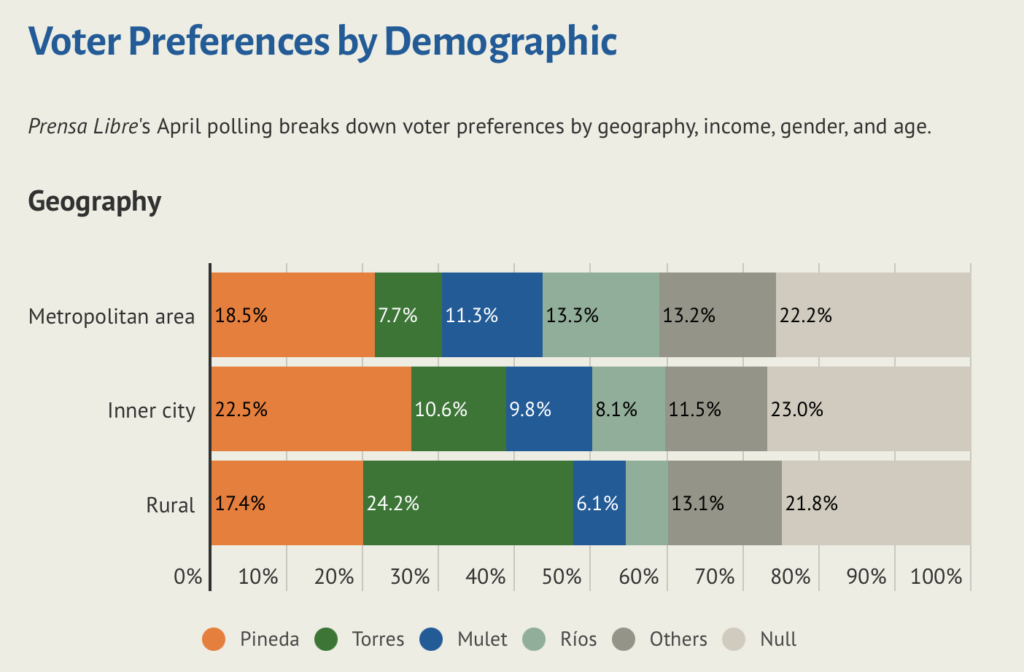

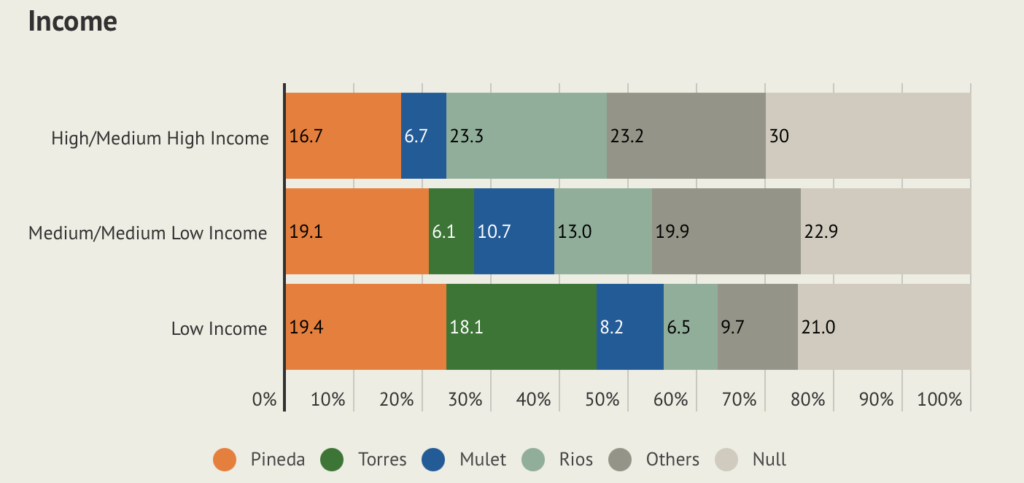

Guatemala’s highest court denied the appeal of Carlos Pineda, a conservative populist who had been leading in the polls. A rival went to court challenging the way Pineda’s party nominated him.

The null votes were widely seen as a protest against the current state of Guatemalan politics, and the fact several candidates were kept out of the race.

The presidential candidacies break down roughly into two ideological positions: 19 on the right and three on the left.

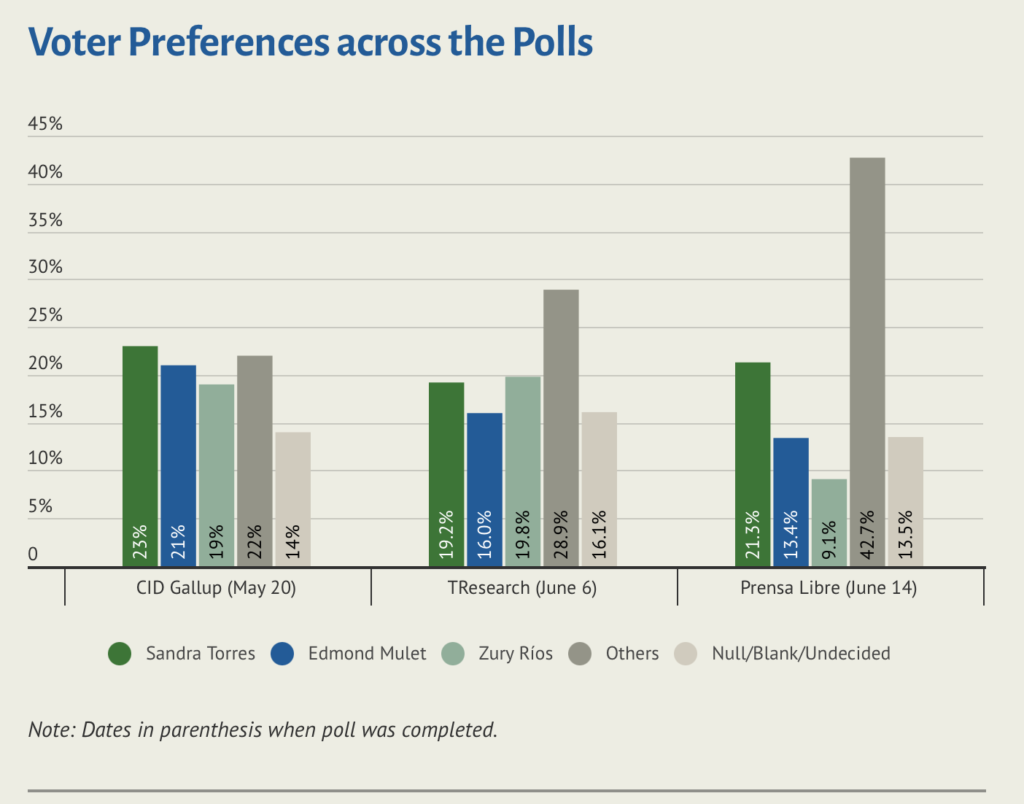

Recent polls indicate the top three contenders are:

- former first lady Sandra Torres;

- Zury Ríos Sosa, daughter of the late dictator Efraín Ríos Mont;

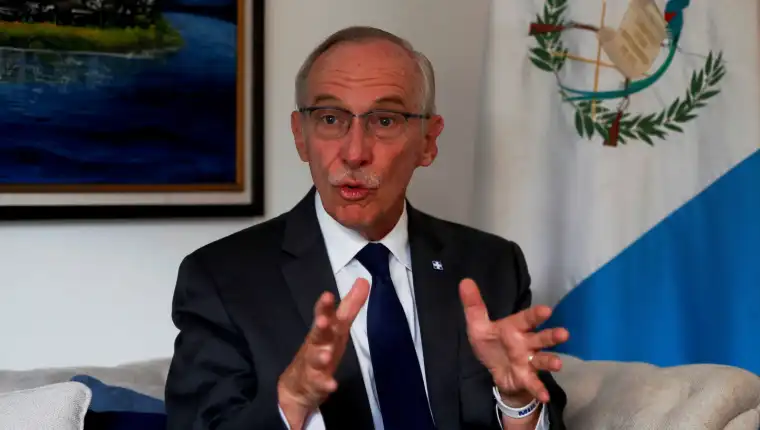

- diplomat Edmond Mulet.

All three are on the more conservative side of the spectrum and have campaigned promising to install tough security measures like President Nayib Bukele in neighboring El Salvador and promoting conservative family values.

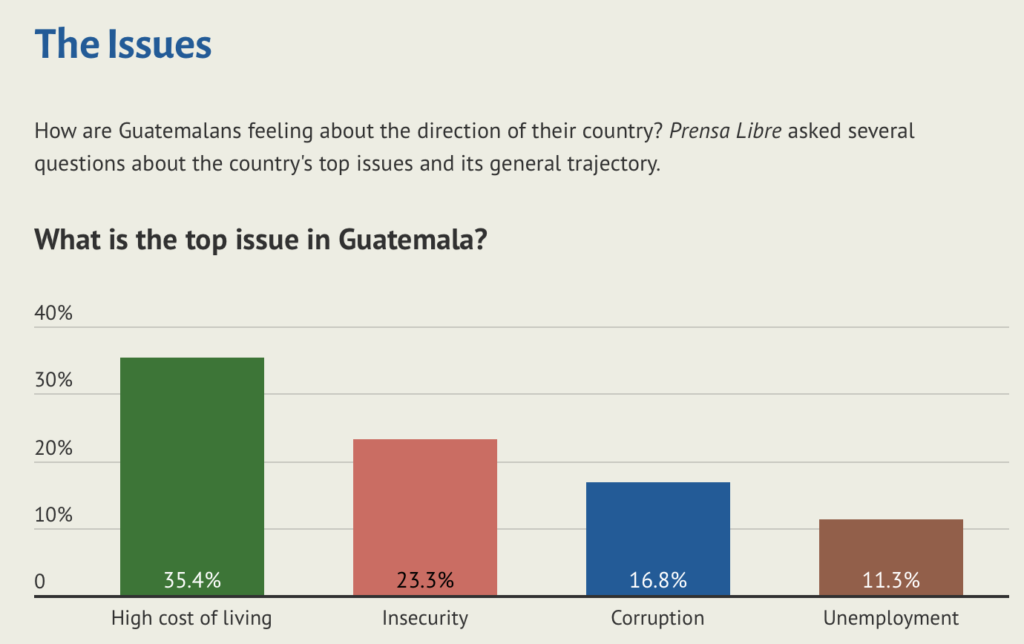

Torres, making her third try to win the presidency, promises bags of basic food items for those in need and cuts in taxes on basic foods. She was first lady during the 2008-2012 presidency of social democrat Álvaro Colom, until they divorced in 2011.

Ríos Sosa is campaigning to establish the death penalty, prohibit government posts for those convicted of corruption, protect private property rights and improve the health system. She was allowed to compete despite a constitutional provision banning candidacies by those who seize power undemocratically — or their relatives.

Mulet says he would give Guatemalans free medicine and support senior citizens and single mothers. He was one of the few politicians who denounced the criminalization of journalists in the country, for which prosecutors accused him of obstruction of justice.

All three candidates signed a pledge promoted to maintain Guatemala’s strict anti-abortion laws, promote conservative values and advocate against recognition of LGBT communities.

On the left, the candidates of the Semilla movement, the VOS party and a coalition made up of URNG-Maiz and the Winaq Political Movement have not done well in the polls. They have campaigned on promises to attack corruption, protect the rights of vulnerable groups and strengthen democracy.

No leftist party has governed Guatemala in almost 70 years, since two leftist administrations from 1945 to 1954. The second of those was led by President Jacobo Arbenz, who was overthrown in a coup.

A series of right-wing military governments and a 36-year civil war that ended in 1996 followed. Since the country’s return to democracy in 1986, the conservative tendency has only been briefly interrupted twice, with centrist social democratic administrations in 1986 and 2008.

Thus, the electorate is highly ideological. Political parties are short lived in Guatemala — since the return to democracy, no party has ever held the presidency twice.

The parties in Guatemala usually get to their first election, compete and gone, because they don’t have enough power to go on.

Read also: Guatemala’s deteriorating democracy