Strong criticism of FGM decriminalization in The Gambia seems to have launched an effort to criminalize the practice in Liberia, as it violates the rights and freedoms of those who undergo it.

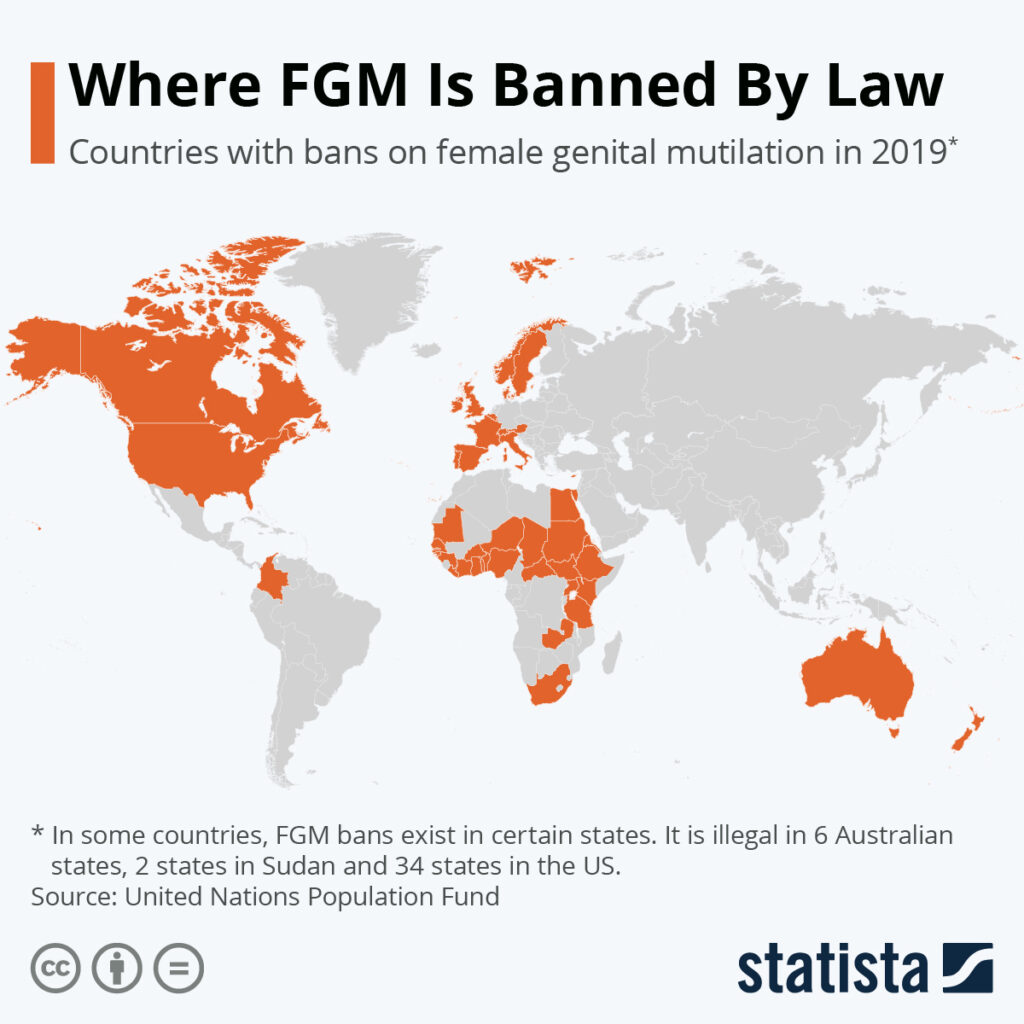

Liberia remains one of the three West African countries without a law criminalizing FGM, despite having signed and ratified regional and international human rights instruments condemning the practice as a human rights violation, including the Maputo Protocol. There has been, however, some progress made to curtail the practice in Liberia.

In a significant move towards protecting the rights and well-being of women and girls, Bong County Electoral District #6 Representative Moima Briggs Mensah announces that Liberia is poised to enact legislation that would criminalize Female Genital Mutilation (FGM).

The pronouncement follows extensive advocacy efforts and awareness campaigns, shedding light on the detrimental effects of FGM on physical and mental health of women and girls.

During a two-day regional consultative workshop on the Role of Traditional, Cultural, and Faith Leaders in Ending Gender-Based Violence (GBV) on Monday, March 11, 2024, in Monrovia, Representative Mensah stressed the 55th Legislature’s commitment to ending the practice but emphasized that traditional leaders’ support is pivotal in this.

According to the female lawmaker, there’s a need for traditional leaders, including Chief Zanzan Kawar, Culture Queen Judy Andy, and all other Zoes in the country, to provide the legislature with a petition document expressing their agreement to criminalize the practice.

She urges her colleagues to include provisions in the petition document for budgetary funding to assist Zoes in obtaining necessary training to abandon their harmful practices.

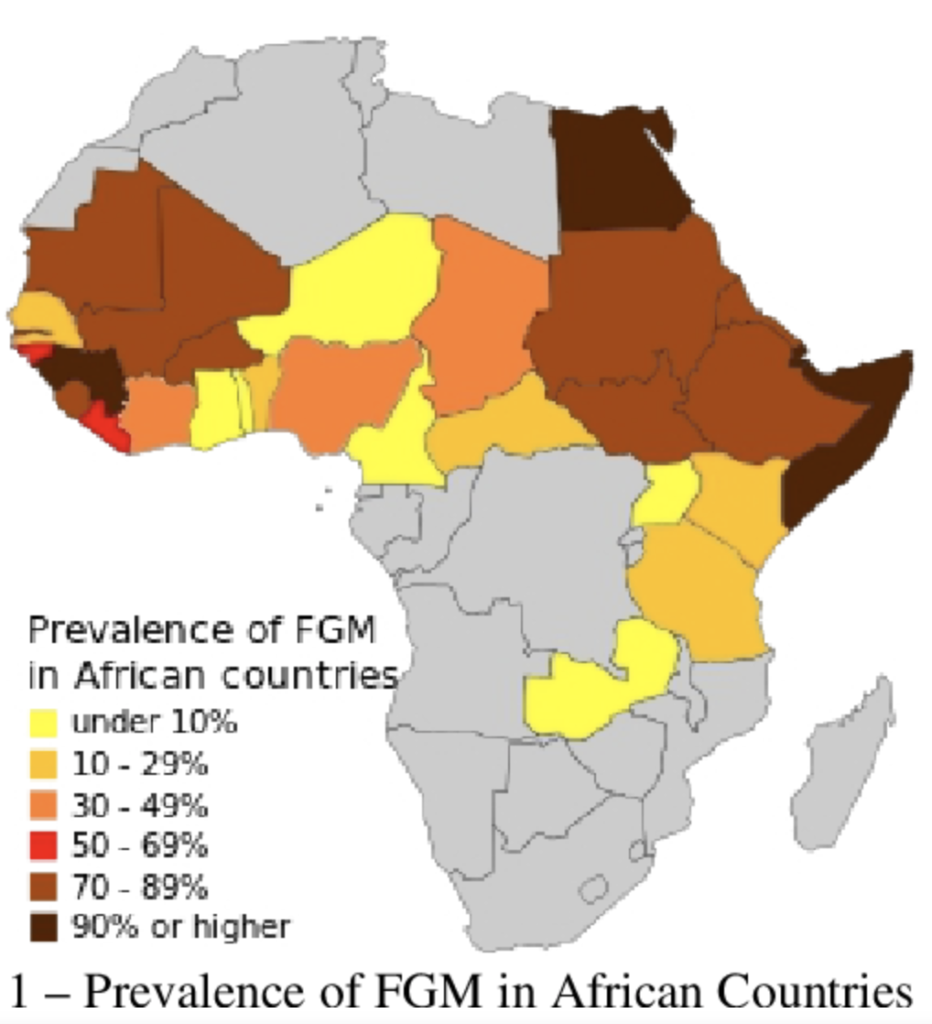

Presently, 31.8% of Liberian women and girls are living with consequences of this harmful practice, and many more are at risk. These women and girls have little choice in this matter, with reports of forced mutilations being common.

However, speaking at the occasion, the District 6 lawmaker revealed that there’s a bill currently in the House’s committee room awaiting passage. Still, he notes that the absence of the traditional leaders to petition the document expressing their consent to pass the law and allocate funds for training is the only obstacle hindering its enactment.

However, previous temporary bans on FGM, like the one in 2018, proved ineffective due to a lack of awareness and coordinated implementation by state agencies. Despite the executive order, the proliferation of Sande bushes in Liberia expanded, now reaching 11 counties compared to the previous 10.

In the absence of a specific law against FGM, few cases have navigated the justice system, typically falling under Section 242 of the Penal Code, which addresses malicious and unlawful injuries resulting in felony charges punishable by up to five years in prison. However, that finds a person guilty of a felony and punishable for up to five years in prison if the person “…maliciously and unlawfully injures another by cutting off or otherwise depriving him of any of the members of his body…” No cases have been reported under this provision for the practice of FGM/FGC,

The declaration by traditional leaders paves the way for Liberia’s Legislature to enact legislation criminalizing the practice. However, challenges persist, as demonstrated by cases such as the Ruth Berry Peal Case. She was said to have been forcibly subjected to FGM in 2011.

Despite initial convictions, perpetrators were released on bail pending appeal, and the case remains unresolved.

Similarly, in 2017, 16-year-old Zaye Doe tragically died during forced mutilation in the Sande bush, highlighting the continued defiance of the government ban on Sande Secret Society operations, including FGM.

Despite the longstanding challenges facing the country, the Bong County Electoral District #6 lawmaker revealed Liberia’s plan to enact legislation criminalizing Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). She indicated that it has to start with a petition document from the traditional council expressing interest in eradicating FGM from Liberia, adding that “this will be the biggest milestone for Liberia this year.”

In addition to the lawmaker’s statement, UN Women Country Representative Comfort Lamptey emphasized that eradicating FGM from Liberia requires bringing everyone together.

She expressed the need to collaborate with lawmakers and leaders to advance this cause and with the community to ensure changes in mindset and approaches.

Moreover, she stressed the importance of traditional leaders embracing the necessary changes to prevent violence against women.

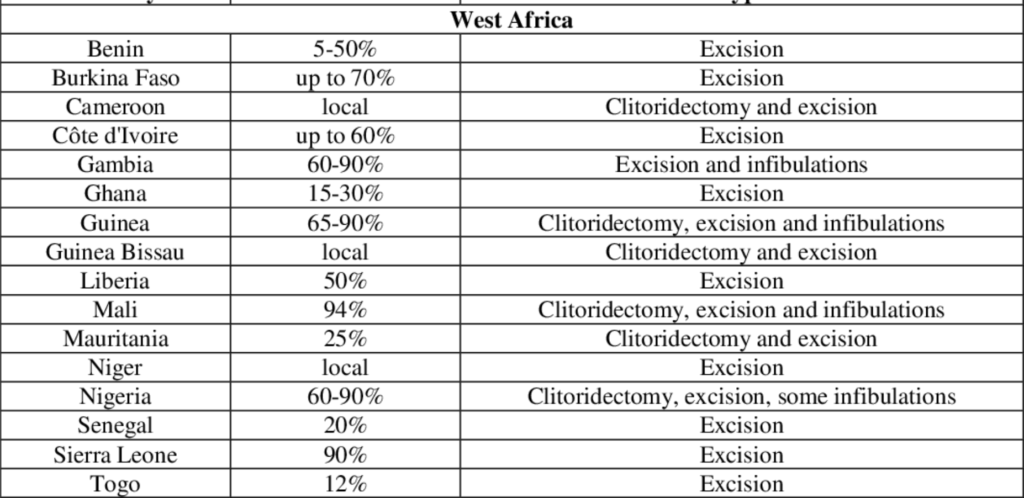

The form of FGM or FGC practiced in Liberia is Type II (commonly referred to as excision). It was customarily practiced by most ethnic groups in Liberia prior to the outbreak of civil war in late 1989.

In areas where traditional institutions were strong, the practice tended to be more frequent. The war, however, brought tremendous dislocation of the population and significantly disrupted rural life and traditional institutions which some believe has resulted in a substantial reduction of the practice.

According to the State Department, exact figures are difficult to ascertain, but a significant portion of the female population has undergone Type II. Some estimates are that, in rural areas, approximately 50 percent of the female population between the ages of eight and eighteen had undergone this procedure before the civil war began. It was practiced within some, but not all of Liberia’s ethnic groups. For those who do, it is their passage from childhood to womanhood.

The major groups that practice it are the Mande speaking peoples of western Liberia such as the Gola and Kissi. It is not practiced by the Kru, Grebo or Krahn in the southeast, by the Americo-Liberians (Congos) or by Muslim Mandingos. So, this practice, obviously, has more to do with traditions than with religious beliefs.

In more urbanized and populated areas such as in Monrovia, the practice was performed or not depending on education and class and how close the family’s ties were to rural life. One well-educated female lawyer in Monrovia underwent the procedure just before she married because she came under strong pressure from an upcountry grandmother. That also goes in line with previous findings on the leading role of family traditions.

Many poor families did not engage in this practice because they could not afford for their daughter(s) to remain six months (and in some cases up to a year) in a secluded traditional school where girls were prepared and initiated into adulthood by older female members of the secret societies.

Social structures and traditional institutions, such as the secret societies that often performed this procedure as an initiation rite, were also undermined by the war.

With the civil war over and traditional societies re-establishing themselves throughout the country, practices such as FGM/FGC are expected to increase again in rural areas for those groups for which it has been a significant and important rite of passage. The extent to which these practices might be revived to pre-war levels is yet unknown.The practice of FGM/FGC has been a part of custom and tradition in more remote areas. The practice has not been as strong, however, within many of the educated and in the urban areas. It is performed during initiation rites into womanhood by older trained members of secret societies.