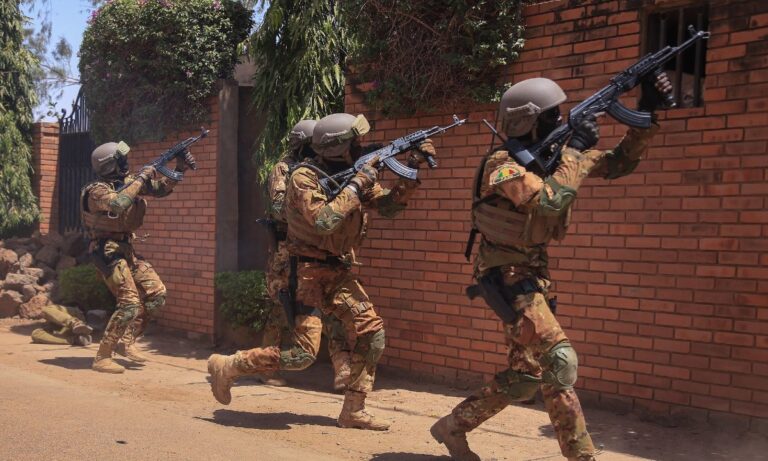

One of the major reasons the junta in Bamako gave for taking power from civilian rulers was the worsening insurgency and insecurity in Mali. According to them, and other coup makers that followed in the region, the “corrupt” civilian governments and their security partners had not been efficacious in fighting terrorism. French forces helped push back Ansar al-Din and AQIM in 2012 and 2013 were seen by the junta as liabilities in the fight. Subsequently, Bamako asked French forces to end their operation and leave the country. This “coincided” with the hiring of the services of Prigozhin-led Wagner to supplant the role of external forces.

More on this story: Russia is countering the USA and EU states in Mali

This notwithstanding, UN forces, despite being restricted by the junta were left to be stationed and operate in the country.

More on this story: Military juntas’ confederation project may be orchestrated in Moscow

In 2023, a UN report on Wagner-backed atrocities by the Malian military became a watershed moment for MINUSMA. The report brought to light summarily executions, indiscriminate attacks on civilians, and other war crimes that mostly occurred in central Mali. Fulbe communities were mostly targeted. Shortly after the report, Mali requested that the UNSC end the mission.

The current report by HRW shows that these abuses have continued and even intensified after the UN forces left. Covering December 2023 to March 2024, the report, according to the organization, shows “horrific abuses”. It added that the Malian authorities are also determined to “eliminate scrutiny” of the situation.

Wagner’s role in Africa is more of a regime protector than a terror fighter. The group’s resume on counterterrorism, apart from some role in Syria, has not been so impressive. This means that much of what the group does in the Sahel is a “muddling through” approach with fear at its core.With Fulbe and Tuareg communities in Central and northern Mali being at the receiving end of such atrocities, the terror “fight” in Mali is largely ethnicized. This is already worsening the security situation as these communities increasingly seek protection with radicals.

The abuses have been concurrent with the junta’s ending of the Algiers Agreement between Bamako and Tuareg rebels. With such marginalization coupled with abuses, extremists are likely to be the beneficiaries—bad news for the entire region.

The shared intensity and scope of the abuse puts regional and continental actors in a difficult place. With the responsibility to protect vulnerable populations, and sanction perpetrators of such abuses combined with the need to meticulously handle fast-changing geopolitics, these actors have limited options.

Most importantly, Wagner’s tactics and strategy have not changed in Mali post-Prigozhin.

More on this story: Africa seeing Russian interference in national legislation shape-up

More on this story: Africa loses gold deposit sovereignty and turns into Russian colony