New threats continue to emerge in the South Sudanese landscape, particularly as December 2024 draws closer.There have been major defections of influential generals from the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-In Opposition. They have expressed dissatisfaction with the progress of reforms and implementation of the current peace agreement.

This strains the delicate balance of power that has existed between the warring factions since 2018. These generals have a substantive following among the public and pose a serious risk to the South Sudan peace agenda. Failure to accommodate these generals could result in insecurity in the regions where they have influence, affecting the chances of holding peaceful elections. A national vote in South Sudanhas been scheduled for December 22, 2024, but the timing remains uncertain, with the United Nations and others doubting whether adequate preparations have been made.

The 2024 election is seen as a pivotal moment for South Sudan, which continues to face challenges in peace-building and governance. A national vote represents a crucial opportunity to solidify a fragile peace and set a course toward a more stable and democratic future.

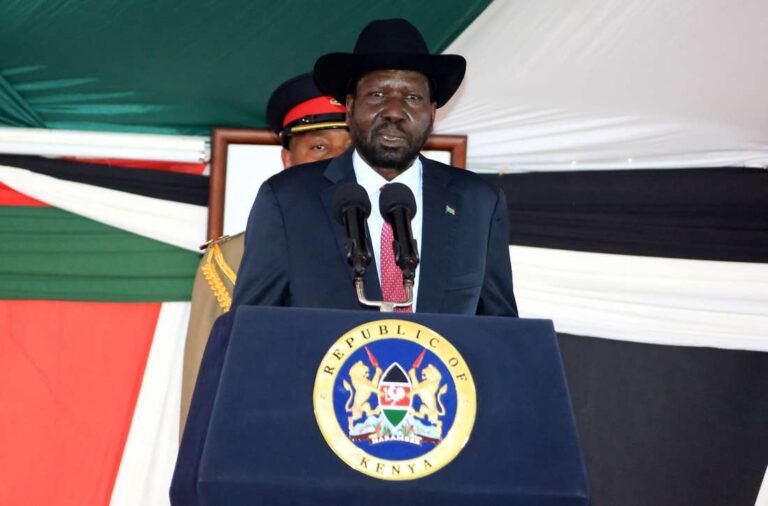

President Salva Kiir and First Vice President Riek Machar, representing the two main parties likely to compete in the election, share a fraught history and a deep mistrust that jeopardizes the integrity of the entire electoral process. The two leaders have been at odds, on and off, since 2013, resulting in civil war. Their complex relationship now threatens the electoral process, with growing concerns over potential ethnic tensions. Kiir wants to reduce his administration’s need to negotiate with political factions in the TGoNU, especially arch-rival Riek Machar’s SPLM in Opposition (SPLM-IO). Kiir wields significant influence in the TGoNU, so if opposition parties boycott the election, he will gain decision-making power, enabling him to govern with fewer obstacles after the polls. This would also allow Kiir to redirect resources currently used to bankroll the excessive bureaucracy of a power-sharing government. The political opposition in the TGoNU, led by the SPLM-IO, lacks the institutional infrastructure and financial resources to effectively compete in the polls. The Kiir-dominated TGoNU has also handicapped the opposition’s chances by stalling the implementation of constitutional, transitional justice and electoral reforms that would level the playing field.

The 2024 vote was poised to shape the future of a country still grappling with the challenges of peace-building and governance – South Sudan entered a post-civil war transitional period in 2018, yet sporadic, mainly intercommunal violence continues. A national vote offers a critical opportunity to consolidate a hard-won peace and chart a course toward a more stable and democratic future.

But the country has failed to establish a robust electoral framework crucial for fair and credible polls – including constitutional, legal, financial and political conditions to ensure the feasibility of holding a credible national ballot. Moreover, entrenched disagreements among political leaders threaten to exacerbate the situation.

As a scholar focusing on global governance and human security in Africa, I share the concern that failure or delay in these electoral processes could lead to a perilous regression into conflict.

Successful elections could elevate South Sudan’s international reputation by demonstrating political maturity and a commitment to democracy after years of instability. Both regional and global actors have urged the government to hold elections promised under the 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan. Amid implementation delays, a road map was endorsed in August 2022 to guide the peace process and elections.

In December 2022, the government reconstituted key bodies, including the National Constitutional Review Commission and the National Electoral Commission, as a precursor to elections. However, both entities face financial challenges, with the National Constitutional Review Commission yet to receive any funding.

These financial problems are a major obstacle. While the National Electoral Commission and the Political Parties Council, a body tasked with promoting political dialogue and cooperation, have received some funding, it is insufficient for full operations. International stakeholders, including the United Nations, the African Union and the EU, had expected the government to finance the elections, but ongoing delays have left international bodies advising and encouraging the government from the sidelines, concerned about the lack of progress.

Rich in oil resources yet extremely poor, South Sudan is currently confronted with a significant decline in its capacity to finance electoral processes. This decline stems primarily from a sharp reduction in oil revenues, compounded by economic hardships and the diversion of resources by the ruling elite.

At independence in 2011, and prior to the conflict that began two years later, South Sudan’s daily oil exports stood at 300,0000 barrels. However, ongoing conflict and infrastructure damage have led to a steady decline in production, with current exports reduced to approximately 150,000 barrels per day. Projections indicate a continued halving of production roughly every five years. Factors exacerbating South Sudan’s oil revenue decline include volatile global oil prices, internal instability and poor-quality crude oil.

Prospective investors are further deterred by war-damaged oil wells and the logistical and political complexities associated with exporting oil through neighboring Sudan. Major oil export disruptions were noted after a disastrous rupture on the crucial pipeline responsible for ferrying landlocked South Sudan’s crude oil to the Red Sea hub of Port Sudan for global export. The rupture occurred during fighting between Sudan’s warring parties: the Rapid Support Forces and the Sudanese Armed Forces.

The payment structure for oil proceeds dictates that private oil companies claim nearly 60% of production as their share, while neighboring Sudan also takes a significant portion based on agreements made during independence. Consequently, South Sudan receives revenue only from approximately 45,000 barrels out of the total daily production ranging from 150,000 to 170,000 barrels. It is from this limited allocation that the government funds 98% of the national budget.

Additionally, the return of over 1 million South Sudanese since the signing of the 2018 peace agreement, along with thousands of refugees fleeing the conflict in Sudan, has further stressed the humanitarian challenges that the young country faces amid economic hardships.

This includes South Sudanese who have been severely affected by the ongoing conflict in Sudan since April 2023. Moreover, alongside this humanitarian burden, there are still thousands of South Sudanese who remain in internally displaced persons camps awaiting a safe return to their communities.

While funding the elections is a challenge, the true crisis lies in a profound lack of trust and confidence between the parties to the peace agreement.

President Salva Kiir and First Vice President Riek Machar – who represent the two main parties that would be competing in any election – share a complicated history and entrenched mistrust of each other that threatens the integrity of the entire electoral process.

The two have clashed and have been on opposing sides off and on since 2013, leading to civil war. Their complex relationship now threatens the integrity of the electoral process amid fears of ethnic tension.

A political struggle between Salva Kiir and Riek Machar led to removal of vice president Machar andviolence erupted between presidential guard soldiers from the two largest ethnic groups in South Sudan. Soldiers from the Dinka ethnic group aligned with Kiir, and those from the Nuer ethnic group supported Machar. Amid the chaos, Kiir announced that Machar had attempted a coup, and violence spread quickly to Jonglei, Upper Nile, and Unity states. From the outbreak of conflict, armed groups targeted civilians along ethnic lines, committed rape and sexual violence, destroyed property, looted villages, and recruited children into their ranks.

The absence of unified national security forces raises concerns about voter safety.

Unlike other post-conflict African countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia and Sierra Leone, where the international community facilitated elections, South Sudan’s transition depends solely on its current transitional government, mandated to lead until December 2024.

If a rumored joint ticket between Kiir and Machar materializes, it could potentially reunite the country and set a course for stability.polls don’t necessarily prevent further violence. In unstable contexts, clashes can occur after reasonably fair elections. Uganda has experienced election-related violence for decades, and Kenya – often seen as the region’s pillar of democracy – faces a violent political crisis partly due to the divisive 2022 elections.