Moldova’s President Maia Sandu Thwarts Russian-Backed Unrest, Successfully Leads Democratic Elections

In a critical moment for Moldova’s democracy, President Maia Sandu and her government managed to maintain stability during the presidential election and a referendum on the country’s European Union integration, despite external pressure and threats of unrest orchestrated by Russian intelligence. Drawing parallels to the 2014 unrest in Ukraine, Russian operatives had reportedly trained groups of young Moldovans in Moscow to incite violence during the elections and protests surrounding the EU referendum.

More on this story: Risk of political unrest high for Moldova

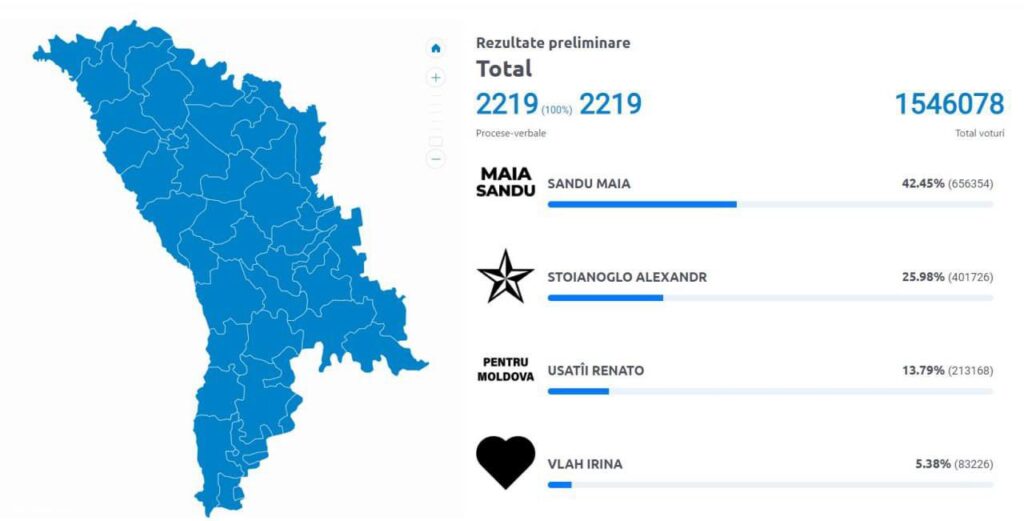

The elections, held under intense pressure, saw 11 candidates vying for the presidency. With nearly all ballots counted, President Sandu leads with 42.3% of the vote, while her main rival, Alexandr Stoianoglo, follows with over 26%. Sandu, a staunch advocate for Moldova’s pro-Western path and EU membership, faces opposition from Stoianoglo, who is backed by the pro-Russian Socialist Party. The party’s leader, former President Igor Dodon, opted not to run but endorsed Stoianoglo. Both Stoianoglo and Dodon are embroiled in legal battles, with Dodon facing charges of corruption and treason, while Stoianoglo is accused of abuse of power.

The referendum on EU integration saw a narrow divide, with 50.4% in favor and 49.6% against. Pre-referendum polls had indicated stronger support for EU membership, leading analysts to attribute the closer result to Russian propaganda and electoral meddling.

The Kremlin’s plans to disrupt the elections reportedly involved recruiting Moldovan youth under the guise of cultural exchanges in Russia. There, they received training in protest organization, confronting police, and, according to Moldovan authorities, even bomb-making and drone use for provocations. Intelligence reports suggest the unrest was to include armed actions in Gagauzia, with demands for the region’s independence. Russian private military contractors, including Wagner Group and “The Farm,” were implicated in training these groups, some of whom were sent for additional instruction in Bosnia and Serbia.

More on this story: Moldova threatened by outside-staged conflict in Gagauzia

Russia also supported several opposition groups, including pro-Russian and pseudo-European parties, with the aim of destabilizing Moldova’s political landscape. Financial backing from Moscow for these operations is estimated at around €100 million, which was intended for bribing voters and other subversive activities.

This hybrid intervention marks Russia’s most significant effort in the post-Soviet space since its destabilization of Ukraine following the 2014 revolution. Beyond its desire to oust the pro-Western Sandu administration, the Kremlin is determined to derail Moldova’s EU aspirations. The situation mirrors Ukraine’s in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and fueled separatism in the Donbas after Ukrainians expressed their desire to integrate with the EU and reject the Eurasian Economic Union. Russia has also tried to tie Moldova’s EU ambitions to the risk of war, highlighting tensions with the separatist region of Transnistria.

Despite these challenges, President Sandu has navigated external interference and election fraud attempts without resorting to authoritarian measures, conducting a transparent democratic process.

The close margin in the referendum, along with the presidential election results, point to a strategic defeat for the Kremlin in Moldova. Historically, Moldovan presidential elections have required a second round, making Sandu’s lead more a reflection of the country’s political dynamics than a shortcoming of her campaign. Likewise, the referendum’s outcome should not be seen as a loss for the government, as Russia offers little alternative beyond nostalgic appeals to Moldova’s Soviet past and the rejection of democratic values embraced by socialist and communist voters.

Unlike her rivals, Sandu remains untainted by corruption scandals. In contrast, pro-Russian candidates like Stoianoglo and businessman Ilan Shor are entangled in legal controversies. The Kremlin’s reliance on corrupt figures in post-Soviet states is not new, as such candidates are easier to control through blackmail and are more willing to engage in corrupt dealings with Moscow. This pattern is evident not only in Moldova but also in Ukraine during the Yanukovych era.

With the elections behind her, Sandu’s victory represents a significant moment for Moldova’s democratic trajectory and its aspirations for closer ties with Europe, in defiance of Russian influence.

However, we doubt that Moscow will refrain from further interference and attempts to destabilize Moldova as preparations for the second round of elections continue. Nevertheless, Sandu’s chances of victory now appear stronger than they did before the first round of voting.

More on this story: Moldovan elections as a battlefield of GRU/FSB interests

More on this story: Moldova leaders risk losing posts over protests inspired from outside