Russia has been actively working to whitewash its atrocities in Africa, leveraging a mix of propaganda, disinformation campaigns, diplomatic maneuvering, and economic influence. Despite accusations of human rights abuses and exploitative practices, particularly through the activities of the Wagner Group, the Kremlin has employed several strategies to reshape its image on the continent.

Russia was responsible for 40% of all disinformation campaigns across the African continent due to its “cognitive warfare” campaign. In these campaigns, local grievances and African colonial history are used to deflect attention from Russia’s atrocities, which include civilian massacres and violations of human rights.

Despite claims by Russian President Vladimir Putin that his country has no record of inhumane acts in Africa, inquiries by the UN, U.S. State Department, and independent investigators confirm that Russian-backed Wagner forces perpetrated atrocities.

Disinformation is a key part of the hybrid warfare that Russia unleashed in Africa in a growing effort to expand its influence and gain control over the continent’s natural resources.

The Russian disinformation operations “pop up repressive regimes and harm civilians. Russia connected to 40% of all disinformation campaigns across the African continent, These operations are cognitive warfare run by the Russian defense ministry.

Russia identifies and inflames local grievances to use them to its advantage. The Kremlin exploits Africa’s history of colonialism to whitewash Russia’s own account of civilian massacres, human rights violations and other atrocities committed in Africa.

More on this story: The Kremlin-affiliated Russian mercenaries are behind war crimes in the CAR

In alignment with that narrative, Russian President Vladimir Putin claimed his country has never done anything inhumane on the African continent.

Russia seeks to position itself as a leader of the Global South, promoting alliances through platforms like BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) and the Non-Aligned Movement. By aligning itself with other emerging economies, Russia attempts to build a coalition that challenges Western hegemony, particularly in Africa.

UN Voting Blocs: Russia uses its influence to rally African countries in international organizations like the United Nations. By securing African support in critical votes, Russia aims to counterbalance Western efforts to isolate it on issues like the Ukraine conflict.

Addressing the audience at the Kremlin’s public relations event, the Valdai International Discussion Club in Sochi on November 7, Putin said:

“In the history of our relations with the African continent, there has never been any shadow – never; we have never exploited African peoples, nor been engaged in anything inhumane on the African continent.”

This is false.

Russia has a dark history of human rights abuses in Africa dating back to the 18th century.

In the present day, multiple investigations by independent rights groups, journalists, think tanks, the United Nations commissions, the U.S. State Department and the European Union accuse Russian state-backed Wagner military group (now African Corps) of committing war crimes and crimes against humanity in Africa.

More on this story: Russians increasingly mixed up in war crimes

More on this story: Africa loses gold deposit sovereignty and turns into Russian colony

The United Nations investigation documented crimes including killing and summary execution of innocent civilians, rape of women and children, torture, force disappearances, pillaging and looting of homes.

In just one incident in Mali, the Russian Wagner forces backed by Malian troops killed upwards of 500 people in Moura village, the U.N. Human rights experts reported in May 2023.

Eyewitnesses recounted to the U.N. investigators how, on March 27, 2022, “a military helicopter flew over the village, opening fire on people, while four other helicopters landed, and troops disembarked. The soldiers corralled people into the center of the village, shooting randomly at those trying to escape.”

The Malian authorities claimed it was “an anti-terrorist military operation” against Katiba Macina, an al-Qaida-affiliated group. The surviving villagers described it as a mass murder and atrocity scene, which continued for five days. “58 women, including young girls, were raped or subjected to other forms of sexual violence” by the Wagner forces and the Malian troops, the survivors told.

The U.S. State Department report in February 2023 documented atrocities committed by Russia in Chad, Libya, Mali, Sudan and Central Africa Republic, CAR.

“The Kremlin-backed Wagner Group forces have razed entire villages and murdered civilians in the Central African Republic [CAR] to advance their economic interests in the mining sector, participated in the unlawful execution of people in Mali, raided artisanal gold mines in Sudan, and undermined democratic institutions in every country where they have worked.”

An investigative report by The Blood Gold Report, an initiative by the Washington-based Consumer Choice Center and its anti-corruption arm 21Democracy revealed the Wagner Group laundered more than $2.5 billion for the Kremlin from trade in African gold since Putin launched his full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

In February, taccording to the U.K.-based Royal United Services Institute, Russia’s military intelligence service was offering the African unstable governments a “regime survival package” that provides military and diplomatic support in exchange for access to natural resources.

The Kremlin also has recruited hundreds of 18- to 22-year-old African women from Uganda, Rwanda, Kenya, South Sudan, Sierra Leone and Nigeria to come to Russia on a false promise of a good job and high wages. Once in Russia, the women are forced to work long hours under constant surveillance for a much lower salary than promised assembling Iranian drones for Russia’s war in Ukraine, The Associated Press reported.

Many African men have fallen for the Russian promise of a good job end up on the front lines, fighting against Ukraine.

More on this story: Kremlin’s Colonial and Racist Policies in Africa

Black foreigners, as well as Russians of African ancestry in Russia, face constant harassment living in an atmosphere of “out of control violent racism,” the British rights watchdog Amnesty International reported.

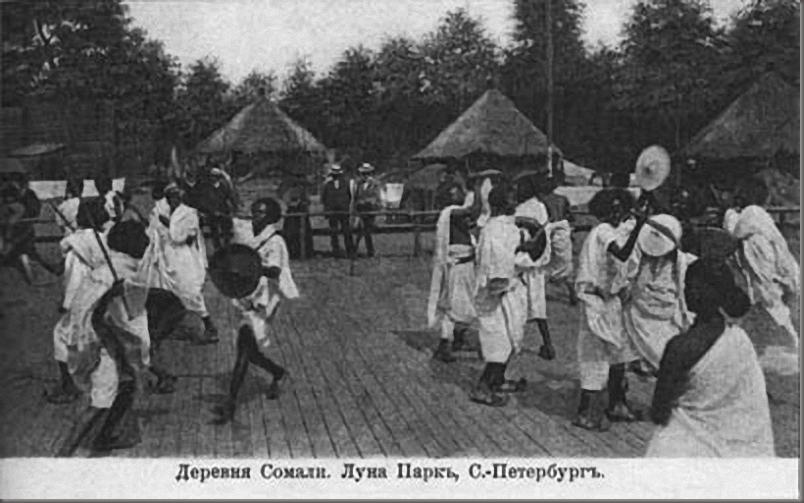

As recently as the 20th century, an amusement park known as Somali village in Luna Park in St. Petersburg, Russia, featured enslaved Africans paraded in cages resembling human zoos.

Further back in history, Russia tried to colonize various parts of Africa but was defeated. In 1889, it claimed Sagallo village, modern-day Djibouti, but it lost its bid to France.

In 1885, Russia was among the countries scrambling for the Red Sea, though it was defeated by Britain in the battle for Sudan and Ethiopia.

The roots of Russian racism in Africa are complex and deeply intertwined with historical, political, and cultural factors that have evolved over centuries. While Russia does not have the same colonial history in Africa as Western European powers, there are several key elements that have contributed to the development of racist attitudes toward Africans.

1. Imperial Russian Ethnocentrism

- Slavic Superiority: During the Russian Empire, there was a strong belief in the cultural and racial superiority of Slavs over non-Slavic peoples. This ethnocentrism was directed at various ethnic groups within the empire, including Asians and indigenous peoples in Siberia and Central Asia. Africans, although less frequently encountered, were often viewed through a similar lens of superiority.

- Orientalism and “Civilizing Mission”: While Russia was not a colonial power in Africa, its imperial ambitions in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and parts of Eastern Europe were accompanied by a “civilizing mission” ideology. This ideology fostered a sense of cultural superiority over non-European peoples, including Africans, who were often depicted as “backward” or “uncivilized.”

2. Soviet Ideology and African Engagement

- Anti-Colonial Solidarity vs. Racist Undercurrents: During the Cold War, the Soviet Union positioned itself as an ally of newly independent African states, offering military, economic, and ideological support. This anti-colonial stance, however, was often underpinned by a paternalistic attitude toward African nations. Africans were seen as “brothers” in the struggle against Western imperialism, but also as “junior partners” who needed guidance from the “socialist big brother.”

- Racist Stereotypes in the Soviet Union: Despite the official ideology of international solidarity, everyday racism was widespread in Soviet society. African students and diplomats who came to study or work in the USSR often faced discrimination, racial slurs, and even violence. These experiences revealed a gap between the Soviet Union’s official rhetoric of racial equality and the reality of societal attitudes.

3. Post-Soviet Xenophobia and Nationalism

- Resurgence of Ethnic Nationalism: After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, there was a resurgence of ethnic nationalism and xenophobia in Russia. Economic hardships and social dislocation led to increased hostility toward foreigners, including Africans. African students and migrants in Russia were often scapegoated for social problems and faced hate crimes.

- As recently as the 20th century, an amusement park known as Somali village in Luna Park in St. Petersburg, Russia, featured enslaved Africans paraded in cages resembling human zoos.

- Political Exploitation of Racism: In the 1990s and early 2000s, Russian nationalist groups gained prominence, promoting ideas of “Russia for Russians.” These groups often targeted non-Slavic populations, including Africans, with their xenophobic rhetoric. The government, while officially condemning racism, sometimes tacitly supported these sentiments to consolidate domestic support.

- The Kremlin’s support for African nations was frequently tinged with a sense of paternalism. African leaders and students were often seen as “junior partners” who needed guidance from their “socialist big brother.” This paternalistic approach suggested that Africans were not capable of managing their own affairs without Soviet oversight, revealing an underlying racial bias masked by ideological rhetoric.

4. Contemporary Russian Neo-Colonialism in Africa

- Economic and Military Interests: In recent years, Russia has re-engaged with Africa, focusing on economic investments, military cooperation, and political alliances. This renewed interest is often driven by strategic motives, such as access to natural resources and geopolitical influence. However, this engagement can also carry undertones of neo-colonial attitudes, where African nations are seen as spheres of influence rather than equal partners.

- Exploitation of Mercenaries: The presence of Russian private military companies, like the Wagner Group, in countries like the Central African Republic, Sudan, and Mali has been marked by accusations of human rights abuses. The treatment of African populations by these mercenaries reflects a disregard for African lives, which can be seen as a form of racist exploitation.

More on this story: Russia uses African mercenaries as consumables in the war against Ukraine

5. Media and Cultural Representation

- Racial Stereotyping in Russian Media: African people are often portrayed in Russian media through stereotypical lenses, either as victims in need of saving or as sources of danger. These depictions reinforce racist attitudes among the public. Even popular culture, including movies and television, has been slow to move away from racist caricatures.

- Propaganda and Soft Power: Russia’s state-controlled media, such as RT and Sputnik, often emphasize anti-Western narratives in Africa, positioning Russia as a friend to African nations against Western “neocolonialism.” However, this rhetoric does not necessarily translate to respect for African people within Russia itself, where Africans continue to face discrimination.

ConclusionThe roots of Russian racism in Africa are multifaceted, stemming from historical ethnocentrism, Soviet-era paternalism, post-Soviet xenophobia, and contemporary neo-colonial ambitions. Despite Russia’s official stance as an ally of Africa against Western dominance, deep-seated racial prejudices continue to shape the interactions between Russians and Africans both within and outside of Russia. This contradiction between official rhetoric and actual societal attitudes underscores the complexity of Russia’s relationship with Africa.

More on this story: War crimes to reflect the essence of Russians