In a move that further entrenches military rule in Mali, the junta leader Colonel Assimi Goita has secured political support to remain in power as president until 2030. This development has significant implications for Mali’s internal stability, regional security, and international relations. The move reflects a growing trend of military-led governments consolidating power in West Africa amid rising jihadist violence and waning democratic governance.

- Political Context and Consolidation of Power

Colonel Assimi Goita came to power through a military coup in 2021, following a second coup within a year. Initially promising a transition to civilian rule, Goita’s government has repeatedly postponed elections, citing security and logistical concerns. The latest extension of his term to 2030 effectively institutionalizes the junta’s rule, sidelining democratic processes and political opposition.

Goita has cultivated a domestic power base by aligning with key sectors of Malian society, including segments of the military elite, influential religious leaders, and traditional community structures. The endorsement to remain in office until 2030 reportedly comes from the National Dialogue process—a mechanism controlled largely by junta loyalists.

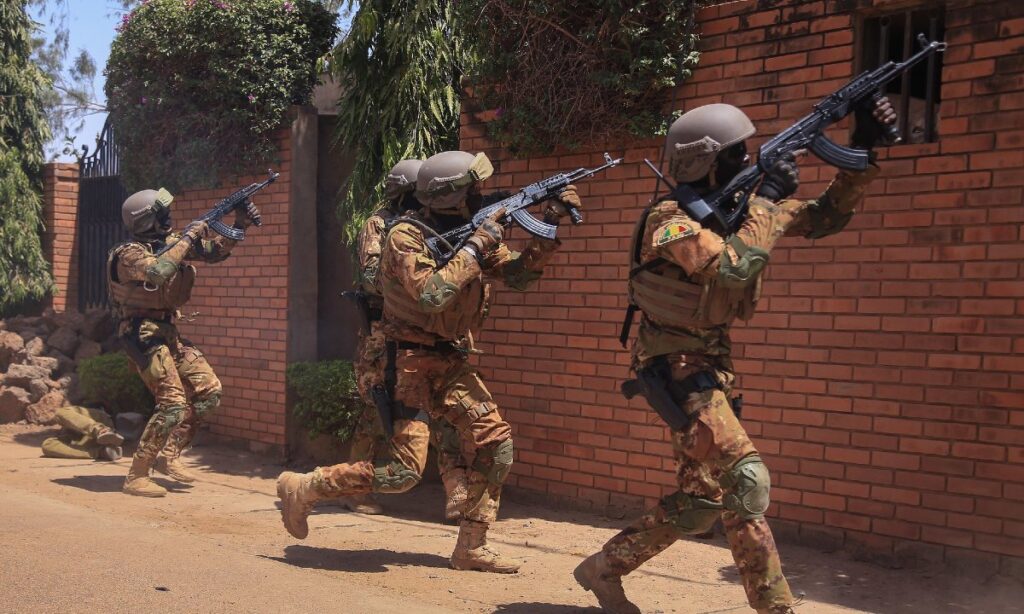

II. Security Dimensions and Strategic Motivations The junta has justified its prolonged rule by citing persistent insecurity, especially in northern and central Mali where jihadist insurgencies by groups affiliated with al-Qaeda and Islamic State remain active. By asserting that a strong, centralized military leadership is required to counter these threats, the junta has framed its rule as a necessary measure for national survival.

Since expelling French forces and the UN peacekeeping mission (MINUSMA), the Goita government has increasingly relied on the Russian Wagner Group for military support. This pivot has coincided with intensified counterinsurgency operations, though human rights abuses and civilian casualties have reportedly increased.

III. Regional and International Repercussions Goita’s extended presidency could deepen instability across the Sahel. Mali’s neighbors—particularly Niger and Burkina Faso, which are also under military rule—may view this consolidation as a model. ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) faces a diminished role as its calls for democratic transition are increasingly ignored.

Internationally, Mali’s alignment with Russia, and the sidelining of Western partners, has reshaped its geopolitical alliances. Western nations, especially the U.S. and France, have condemned the democratic backsliding, while China and Russia have been more accommodating.

IV. Risks and Potential Outcomes The institutionalization of military rule carries significant risks:

- Democratic Erosion: The sidelining of democratic institutions erodes Mali’s political legitimacy and risks alienating reformist and youth movements.

- Insurgency Resurgence: Jihadist groups may exploit governance vacuums, especially in marginalized communities.

- Economic Strain: Mali faces donor fatigue and economic isolation, as Western aid is curtailed in response to the junta’s extended rule.

- Human Rights Concerns: Increased militarization and the presence of Wagner operatives have been associated with extrajudicial killings and suppression of dissent.

Colonel Assimi Goita’s consolidation of power until 2030 marks a pivotal moment in Mali’s political trajectory. While presented as a measure to ensure national stability, it risks deepening the country’s isolation and exacerbating internal divisions. The international community must weigh its options carefully—balancing the need to support Malian sovereignty with the imperative to promote governance, human rights, and long-term stability in the Sahel.

The extension of Mali’s junta leadership under Colonel Assimi Goita until 2030 could have profound effects on intertribal relations across the country:

V. Impact on Intertribal Relations in Mali

Mali is a highly diverse country with over a dozen major ethnic and tribal groups, including the Bambara, Tuareg, Fulani, Songhai, Dogon, and others. The prolonged rule of a centralized military regime risks upsetting the fragile balance of influence and representation among these communities.

1. Marginalization of Peripheral Tribes The junta’s power base is primarily located in Bamako and southern Mali, particularly among the Bambara-dominated military elite. This risks alienating northern tribes such as the Tuareg and Arab populations, who have long-standing grievances related to political exclusion and underdevelopment. Goita’s presidency, lacking electoral legitimacy, provides few institutional channels for these groups to participate or voice concerns.

2. Intensified Ethnic Tensions in the Center Central Mali, particularly the Mopti region, has seen violent conflict between Dogon and Fulani communities. The militarized response to jihadist threats—often perceived as targeting Fulani populations—could worsen perceptions of state bias and further polarize intercommunal relations.

3. Undermining Traditional Conflict Mediation Tribal leaders and local elders have historically played key roles in mediating disputes and maintaining social cohesion. The junta’s centralization of power and its alliance with external actors like the Wagner Group undermines local authority structures, potentially eroding traditional methods of reconciliation.4. Risk of Tribal Rebellions or Separatist Movements Should Goita’s rule become increasingly autocratic or repressive, there is a real risk that northern tribal groups—particularly Tuareg factions with prior experience in rebellion—may once again push for autonomy or secession. Past peace agreements, like the Algiers Accord, may unravel under such strain.

More on this story: Regime in Mali wends Syria’s way

More on this story: The worsening insurgency and insecurity in Mali