In the evolving theater of hybrid warfare, cyber espionage has become a key instrument of state power. Recent reports and security assessments indicate a disturbing trend: Russian state-linked hackers have increasingly targeted surveillance and traffic camera systems across European Union (EU) border states, particularly those bordering the Russian Federation or its spheres of influence.

1. Strategic Goals of Russian Camera Hacking

a. Intelligence Gathering

Russian hacking operations aim primarily to gain real-time intelligence on troop movements, NATO logistics, border security protocols, and critical infrastructure vulnerabilities. Surveillance cameras—particularly those located at military bases, transportation hubs, or near sensitive installations—are a low-cost but high-reward intelligence source. ussia uses hacked surveillance systems to observe and track cross-border movements of military equipment and personnel — especially shipments of Western military aid to Ukraine. The ability to observe real-time logistical flows gives Moscow an opportunity to assess the scale, timing, and routes of critical deliveries.

b. Mapping Vulnerabilities and Testing Defenses

These cyber intrusions act as reconnaissance missions for more damaging future operations. By exploiting cameras, Russia can map the cyber defenses of NATO’s digital infrastructure and test how quickly local cybersecurity units detect and respond to intrusions.

c. Psychological and Information Warfare

Successful hacks serve to intimidate EU states and weaken public trust in their governments’ ability to ensure national security. When such breaches are made public, they create a narrative of NATO vulnerability and Russian technological superiority.

d. Support for Hybrid Operations

Camera surveillance hacks may support clandestine operations such as cross-border sabotage, disinformation efforts, or the movement of agents and operatives. They are part of a broader hybrid strategy that blurs the line between war and peace, military and civilian targets.

2. Threats to NATO and Bordering EU States

a. Compromised Situational Awareness

NATO’s situational awareness along its eastern flank is critical. If surveillance feeds are accessed or disrupted, the Alliance risks losing crucial early-warning capabilities. This makes border zones more vulnerable to infiltration or surprise actions.

b. Operational Security Risks

Leaked or intercepted footage from military convoys, training exercises, or troop deployments can compromise operational security (OPSEC). Russian intelligence can use this to adjust its own posture or feed into disinformation campaigns about NATO’s intentions.

c. Threat to Civil-Military Infrastructure

Surveillance systems often serve dual purposes, monitoring both civil and military domains. Hacking them can interfere with public safety operations, border control, and law enforcement, compounding the challenge of responding to hybrid threats.

d. Trigger for Escalation

Repeated or blatant camera hacks could be interpreted as provocations or cyberattacks under NATO’s Article 5. While most such incidents stay below the threshold for collective response, cumulative actions increase the risk of escalation or miscalculation.

3. Kremlin’s Broader Strategic Purpose

a. Asymmetrical Warfare Advantage

Russia understands it cannot match NATO’s conventional strength. Cyber operations like camera hacking provide a cheap, deniable, and effective asymmetrical tool to project power and challenge NATO cohesion without risking open confrontation.

b. Deterrence and Counterbalance

By showing it can breach EU states’ surveillance systems, Russia sends a deterrent message: “You watch us, but we watch you too.” It seeks to discourage further NATO military build-up near its borders and signal that no action goes unnoticed.

c. Manipulating Political Discourse in Europe

If hacking incidents are leaked or exploited, Russia can sow political divisions within EU and NATO countries. Blame games over security failures, calls for disengagement, or panic about surveillance weaknesses play into the Kremlin’s disinformation goals.

d. Integration with Wider Cyber-Espionage Campaigns

Camera hacks are not isolated. They often occur alongside broader campaigns targeting government ministries, defense contractors, and media. The Kremlin integrates such operations into a long-term intelligence-gathering and destabilization strategy.

4. Case Examples (Briefly Mentioned)

- Poland and the Baltic States have reported increased cyber intrusions in 2023–2024, including unauthorized access to transportation surveillance networks and infrastructure monitoring systems.

- Finland, since joining NATO, has become a heightened target, with its border sensors and surveillance grids experiencing persistent cyber probing.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Russia’s hacking of surveillance cameras along NATO’s eastern flank reveals an intent to undermine border security, gather intelligence, and test Alliance defenses through low-level but persistent cyber aggression. This strategy fits within the Kremlin’s broader asymmetric warfare doctrine.

To counter these threats, NATO and EU states should:

- Harden civilian and military camera networks, prioritizing air-gapped or encrypted systems.

- Increase joint cyber monitoring through NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE).

- Establish clear attribution and response protocols to deter future intrusions.

- Invest in AI-based anomaly detection to flag suspicious access to camera systems.

- Educate local operators and municipalities, who often run vulnerable infrastructure, on basic cyber hygiene.

Only through coordinated, resilient defense can the Alliance protect its digital borders as effectively as its physical ones.

4. Link Between Surveillance Hacks and Military Aid to Ukraine

Russia’s targeting of surveillance systems is directly connected to its strategic interest in disrupting the flow of Western military aid to Ukraine. Key dynamics include:

- Real-Time Monitoring of Convoys: Polish intelligence has confirmed incidents where hacked road surveillance systems near Rzeszów (a major aid logistics hub) were used to track aid convoys headed toward the Ukrainian border.

- Mapping and Timing Attacks in Ukraine: There is growing concern that surveillance hacks are being used to coordinate missile or drone strikes on Ukrainian territory. Several attacks on depots and rail nodes in western Ukraine occurred shortly after large aid shipments passed through EU territory.

- Counterintelligence Coordination: NATO believes that camera hacks are often coordinated with Russian human intelligence (HUMINT) networks in Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary. These networks reportedly provide metadata from hacked systems to assist in planning further operations.

- Pressure on Logistics States: Russian cyber operations targeting surveillance in states like Poland and the Baltic countries are designed to increase political pressure domestically. By creating narratives around insecurity and NATO entrapment, Russia seeks to weaken support for ongoing military assistance to Ukraine.

Case Studies and Attribution

a. Poland (2023–2024)

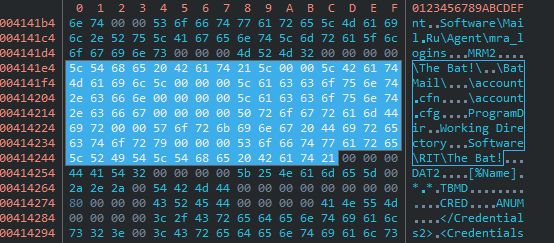

The Polish Internal Security Agency (ABW) reported multiple incidents in which cameras along key highways leading to Ukraine were hacked and remotely accessed. These included attempts to disable feeds or loop previous footage — classic signs of covert surveillance.

b. Lithuania and Latvia

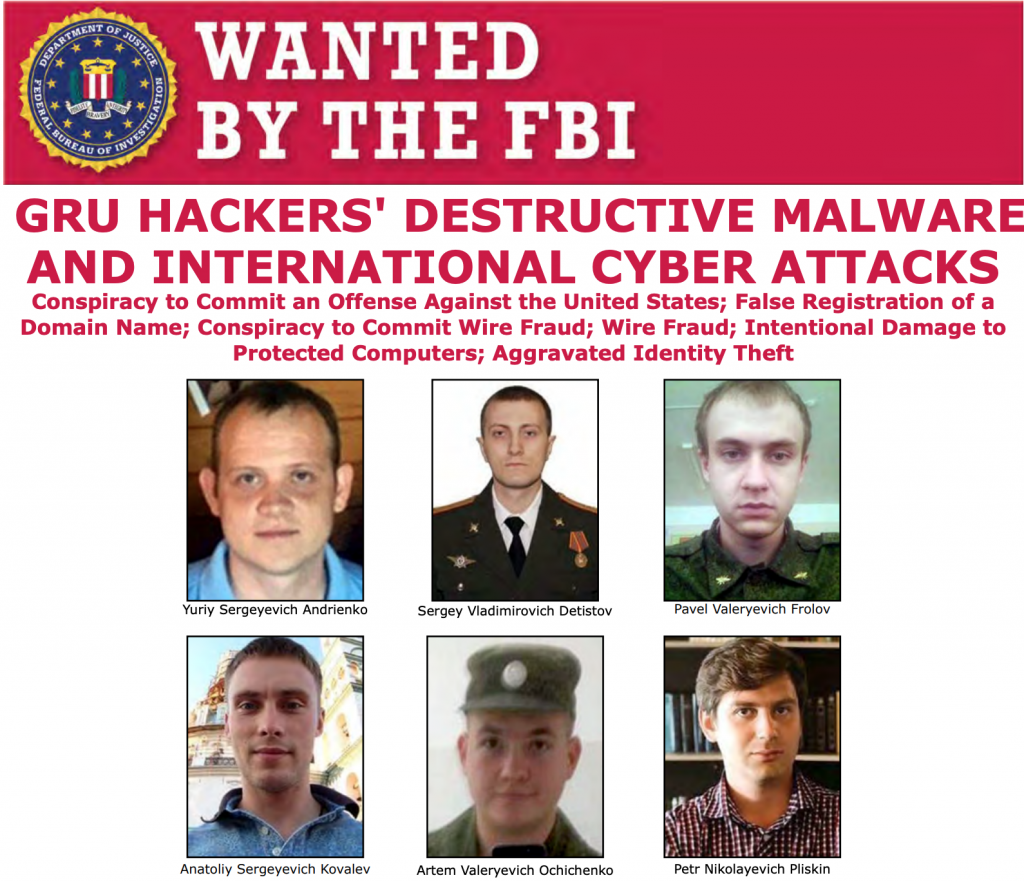

Baltic officials reported breaches in customs and border surveillance networks, particularly around NATO Enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) deployment zones. Lithuanian CERT identified malware linked to APT28 (Fancy Bear) — a well-known GRU cyber unit.

c. Finland

After joining NATO, Finland’s surveillance systems along its eastern border experienced a sharp uptick in intrusion attempts. Officials suspect these were dry runs for longer-term destabilization efforts targeting NATO infrastructure and aid monitoring.

d. Germany and Czech Republic

While not frontline states, both have reported suspicious activity around railway surveillance systems and military installations used for aid transshipment. The Czech National Cyber and Information Security Agency attributed at least one incident to Sandworm — another Russian military intelligence (GRU) cyber unit.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Russia’s hacking of surveillance systems in bordering EU states is a central pillar of its broader hybrid war strategy. These operations serve both tactical goals—such as tracking military aid to Ukraine—and strategic ones, such as weakening NATO cohesion, testing cyber defenses, and exploiting political divisions.

Recommendations for NATO and EU states include:

- Cyber Shielding of Aid Corridors: Deploy hardened, encrypted, and AI-monitored surveillance systems along all known aid routes.

- Counter-Cyber Intelligence Integration: Link cyber monitoring with military logistics command to prevent real-time exploitation.

- Attribution and Response Frameworks: Move toward public attribution and diplomatic costs for Russian cyber aggression.

- Civil-Military Cyber Training: Train local infrastructure operators on security procedures and basic anomaly detection.

- Proactive Disinformation Monitoring: Anticipate and neutralize Russian efforts to use surveillance breaches in propaganda campaigns against NATO aid efforts.

Key Similarities Between Russian and Chinese Cyber Intelligence Tactics

1. Use of “Gray Zone” Operations

Both Russia and China operate in the gray zone between peace and war—leveraging cyber operations that fall below the threshold of open conflict but can have strategic effects. This includes:

- Targeting surveillance networks

- Infiltrating critical infrastructure

- Avoiding immediate attribution or using proxy actors

2. Focus on Dual-Use Infrastructure

Both states frequently target civilian infrastructure with military or intelligence value—such as:

- Surveillance cameras at ports, airports, border zones

- Power grids, water systems, and transport logistics

- Telecommunications and fiber-optic networks

These targets provide access to both real-time intelligence and a means for long-term positioning for future conflict or coercion.

3. Long-Term Strategic Positioning

Chinese and Russian hackers often pre-position malware or backdoors in infrastructure that may not be exploited immediately. Instead, these “sleeper” intrusions serve as insurance for future leverage or disruption.

- Russia’s Sandworm and APT28 are known for planting destructive malware.

- China’s Volt Typhoon, as revealed in 2023 by the U.S., infiltrated critical U.S. infrastructure to prepare for a future conflict scenario—especially concerning Taiwan.

4. Exploitation of Supply Chains and Local Contractors

Both countries exploit third-party vulnerabilities to access sensitive systems. This includes:

- Surveillance tech vendors

- IT maintenance companies

- Municipal service providers

This mirrors the tactics used in Russia’s hacking of EU surveillance cameras via public infrastructure networks, and China’s hacking of contractors tied to U.S. defense and telecom companies.

5. Use of State-Aligned Hacker Groups (APTs)

Both Russia and China use Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups tied to state intelligence services:

| Country | Prominent APTs | Known For |

| Russia | APT28 (Fancy Bear), Sandworm | Military & hybrid warfare ops |

| China | APT41, Volt Typhoon, Hafnium | Espionage & strategic infiltration |

These groups conduct cyberespionage, network mapping, credential theft, and in some cases, surveillance tampering.

6. Intelligence for Strategic Messaging & Coercion

Both regimes use hacked data or infrastructure access to send strategic signals or coerce rivals:

- Russia leaks surveillance footage or sabotages it to induce panic or demonstrate power.

- China uses data extracted from global surveillance platforms (e.g., via Hikvision) to pressure foreign firms or governments (e.g., over Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang).

Notable Differences

Despite these similarities, key differences shape their cyber operations:

| Factor | Russia | China |

| Style | Aggressive, disruptive | Stealthy, long-term |

| Tactics | Sabotage, propaganda, battlefield support | Strategic espionage, economic theft |

| Risk Tolerance | High – often seeks escalation | Low – prefers deniability |

| Primary Targets | Military, political, infrastructure in conflict zones | Tech, supply chains, long-term control |

| Global Footprint | Focused on NATO & post-Soviet space | Global, especially Indo-Pacific, U.S., and Africa |

In Summary

Yes, Russia and China both employ similar cyber intelligence tactics, including:

- Surveillance camera hacking

- Civilian infrastructure infiltration

- Use of state-aligned APTs

- Pre-positioning for future crises

- Operating under the gray-zone warfare model

However, Russia tends to use these tactics more tactically and disruptively, often linked directly to a current military conflict (e.g., Ukraine), while China employs them in a strategic, long-term context — aiming for dominance in technology, global supply chains, and geopolitical pressure, especially over Taiwan and the South China Sea.

More on this story: Cyber espionage and Russia’s intelligence hack activities

More on this story: Kremlin operations increase risks for European railways.

More on this story: An Act of War: The Kremlin’s Relentless Cyber Attacks on the United States