The Kremlin has institutionalized a vast effort to expropriate Chinese nuclear technologies under the guise of international cooperation. This policy, sanctioned at the highest political level, involves diplomats, intelligence operatives, and officials from Rostekhnadzor and Rosatom.level, involves diplomats, intelligence operatives, and officials from Rostekhnadzor and Rosatom.

The accelerating decay of Russia’s nuclear sector, driven by financial constraints and technological stagnation, has forced the Kremlin to turn to theft and covert operations under slogans of “friendship” and “partnership.” As Rosatom increasingly fails to meet its obligations, espionage has become a strategic substitute for innovation.

On May 8, 2025, Rosatom Director General Alexey Likhachev publicly stated that the Russian state nuclear corporation is in discussions with Chinese partners to build new nuclear power units. This statement, made during an interview with TASS, indicates that talks have been ongoing since late 2018.

Background: Alexey Likhachev is a senior Russian official who has led Rosatom since 2016. The corporation encompasses all civilian nuclear enterprises in Russia, defense nuclear industry facilities, research institutions, and the Russian nuclear fleet.

Likhachev’s statement requires careful scrutiny, as Russia and China have long cooperated in the nuclear field. To date, the two countries have jointly constructed four nuclear power units in China, with four more currently under construction. Operating reactors include four VVER-1000 units built with Rosatom’s participation. In addition, four VVER-1200 reactors are being constructed—two at the Tianwan NPP and two at the Xudabao NPP.

The Strategic Intent Behind Cooperation

A closer look reveals that Russia’s nuclear cooperation with China serves not only commercial interests but also a strategic espionage agenda. The Kremlin views its engagement with Chinese counterparts as a unique opportunity to acquire critical nuclear technologies—most notably, China’s cutting-edge high-temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTGR) technology using spherical micro-fuel elements under the HTR-HM project, which is currently absent in Russia’s technological arsenal.

Russian intelligence services, particularly the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), are actively seeking to penetrate Chinese companies and research institutes under the guise of formal contracts. Their ultimate objective is to obtain access to proprietary Chinese innovations—specifically the HTR-PM, one of the most advanced small modular reactors (SMRs) with a capacity of 210 MW, the first of which went online at the Shidaowan Nuclear Power Plant in Shandong province in late 2023.

Motivations and Context

This aggressive espionage campaign is fueled by two key factors: (1) Russia’s historical reliance on illicit technology acquisition, often coordinated by its intelligence agencies, and (2) the growing technological isolation of Russia following Western sanctions, which have blocked most advanced countries from scientific and technical cooperation with Moscow.

China’s continued engagement with Russia makes it an indispensable source of innovation for the ailing Russian nuclear sector. With Rosatom’s 2025 projects funded at only 20–30% of their required budget—due in large part to the Kremlin’s prioritization of war spending—Russia’s nuclear industry is in decline and struggling to fulfill contractual obligations. Thus, China remains Russia’s last hope for salvaging its deteriorating atomic capabilities.

The Role of Vienna and the IAEA

Vienna, known as the global capital of espionage, plays a pivotal role in Russia’s technological intelligence operations. The SVR has embedded a covert station, known as “Vienna-2,” within Russia’s Permanent Mission to International Organizations in Vienna. This network leverages institutional cover from both the IAEA and the OSCE.

Simultaneously, a second station—“Vienna-1”—operates from the Russian Embassy, encompassing political, economic, scientific-technical, and counterintelligence lines. These two outposts coordinate intelligence activities targeting Chinese nuclear expertise.

The Deputy Permanent Representative of the Russia to International Organizations in Vienna, Daniil Mokin, discreetly explored ways to establish contact with key Chinese specialists during informal discussions with his own contacts — namely, the Permanent Representative of the People’s Republic of China to International Organizations in Vienna, Song Li, and the Deputy Head of the Chinese diplomatic mission, Guanghui Liu.

In the same area, Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) actively utilizes its officers and operational sources embedded within the State Atomic Energy Corporation “Rosatom” and the Federal Service for Environmental, Technological and Nuclear Supervision (“Rostechnadzor”). Their main goal is to establish contacts for the potential recruitment of personnel from the China Huaneng Group (CHNG), the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), researchers from the Institute of Nuclear and New Energy Technology at Tsinghua University, engineers from the world’s first fourth-generation nuclear power plant “Shidaowan” (Shandong Province, PRC), and officials from Chinese nuclear regulatory bodies who may have access to data and technical documentation related to the HTR-PM project.

In September 2024, during the 68th session of the IAEA General Conference in Vienna, negotiations took place between the head of Rostechnadzor, Aleksandr Trembitsky, and the head of China’s National Nuclear Safety Administration (NNSA), Dong Baotong.

Notably, no information about these talks with the Chinese side appears on Rostechnadzor’s official website. This indicates Russia’s unwillingness to publicize such contacts, thereby underscoring their particular importance to the Kremlin. The negotiations focused on amending the interagency agreement between Rostechnadzor and the NNSA in light of new challenges, cooperation in organizing scientific and technical support, and the prospects for interaction within the Multinational Design Evaluation Programme (MDEP) of the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA).

A striking example involves Russian attempts to access HTR-PM technologies through informal meetings between Rosatom and IAEA Secretariat personnel and Chinese diplomats in Vienna. Deputy Permanent Representative of Russia to International Organizations in Vienna, Daniil Mokin, discreetly pursued contacts during unofficial talks with Chinese officials, including Song Li (Permanent Representative of China to International Organizations in Vienna) and Guanghui Liu (Deputy Head of China’s diplomatic mission).

On December 20, 2021, China marked a historic milestone by connecting the world’s first High-Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor (HTR-PM) to the grid at the Shidao Bay Nuclear Power Plant. This development, supported by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), not only confirms China’s leadership in advanced nuclear technologies but also has significant strategic, economic, and geopolitical implications. Moreover, the technological sophistication and civil-military potential of the HTR-PM reactor raise security concerns regarding foreign interest and potential espionage, particularly from Russia.

The HTR-PM is a modular high-temperature gas-cooled reactor with a unique pebble-bed core and helium cooling system. Its main features include:

- Enhanced Safety: Inherently safe design that prevents meltdown even in case of coolant loss.

- High Efficiency: Capability to operate at 750–950°C, offering higher thermal efficiency than traditional light-water reactors.

- Versatility: Potential for industrial applications beyond electricity generation, including hydrogen production and desalination.

This breakthrough reflects decades of Chinese investment in nuclear R&D, underpinned by international cooperation, including technical support from the IAEA.

China’s pursuit of the HTR-PM program is driven by a mix of domestic and international motivations:

- Energy Security: Reducing dependence on coal and foreign fossil fuels.

- Climate Policy: Supporting carbon neutrality targets by 2060.

- Industrial Autonomy: Creating exportable, independent nuclear technologies, which can compete with U.S., Russian, and French designs.

- Dual-Use Potential: The HTR’s ability to produce weapons-grade isotopes or high-temperature hydrogen makes it strategically sensitive.

The Chinese HTR-PM has emerged as a game-changer in the international nuclear marketplace. Its modular, safe, and export-friendly design challenges the market dominance of traditional suppliers, including Russia’s Rosatom. From a geopolitical perspective, this triggers the following dynamics:

- Export Rivalry: China could target emerging markets in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East—areas where Rosatom traditionally dominates.

- Technological Benchmarking: Russia may seek to replicate or neutralize China’s HTR technology to protect its own global market share.

- Espionage Risk: Given China’s growing technological independence, Russian intelligence services may attempt to acquire classified information under the guise of IAEA cooperation or bilateral nuclear exchanges.

There are credible indications that Rosatom-linked structures and Russian diplomatic missions may be seeking access to China’s HTR innovations. Espionage activities could be aimed at acquiring design documents, fuel cycle details, or data on helium-cooling operations.

Russia also utilizes internal assets within Rosatom and the Federal Environmental, Industrial and Nuclear Supervision Service of Russia (Rostekhnadzor) to establish relationships with potential targets for recruitment.These include employees of:

- China Huaneng Group (CHNG),

- China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC),

- The Institute of Nuclear and New Energy Technology at Tsinghua University,

- Engineers of the Shidaowan fourth-generation nuclear plant,

- Officials from China’s nuclear regulatory bodies.

- The Kremlin has institutionalized a vast effort to expropriate Chinese nuclear technologies under the guise of international cooperation. This policy, sanctioned at the highest political level, involves diplomats, intelligence operatives, and officials from Rostekhnadzor and Rosatom.

- The accelerating decay of Russia’s nuclear sector, driven by financial constraints and technological stagnation, has forced the Kremlin to turn to theft and covert operations under slogans of “friendship” and “partnership.” As Rosatom increasingly fails to meet its obligations, espionage has become a strategic substitute for innovation.

In September 2024, during the 68th IAEA General Conference in Vienna, Alexander Trembitsky (head of Rostekhnadzor) met with Dong Baotong, head of China’s National Nuclear Safety Administration (NNSA). The absence of any mention of these talks on the official Rostekhnadzor website suggests the Kremlin’s intent to conceal the meeting, underscoring its strategic significance.

The discussions focused on amending the inter-agency agreement between Rostekhnadzor and the NNSA in response to new challenges, enhancing scientific-technical cooperation, and exploring future collaboration under the OECD’s Multinational Design Evaluation Programme (MDEP).

Despite public rhetoric about Russian-Chinese friendship, Russia’s intelligence services continue to exploit IAEA-affiliated events not only to monitor Western adversaries but increasingly to target friendly nations like China. Their main targets remain:

- Employees of CHNG and CNNC,

- Scientists from Tsinghua University,

- Engineers at Shidaowan NPP,

- Chinese nuclear regulatory officials.

On December 20, 2021, China achieved a historic milestone by connecting the world’s first high-temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTR-PM) to the grid at the Shidaowan nuclear power plant. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) officially confirmed the event on January 13, 2022. However, behind this technological triumph lies a developing counterintelligence concern: the growing interest of Russian intelligence agencies, particularly those linked to Rosatom and the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), in accessing the sensitive technological components of the Chinese HTR-PM program. This paper analyzes the underlying structure of the reactor project, its strategic significance, and the concerted efforts by Russian intelligence to infiltrate and extract proprietary data—efforts that pose a serious threat to Chinese technological sovereignty and global nuclear innovation.

Rosatom Takes the Lead in Technology Theft

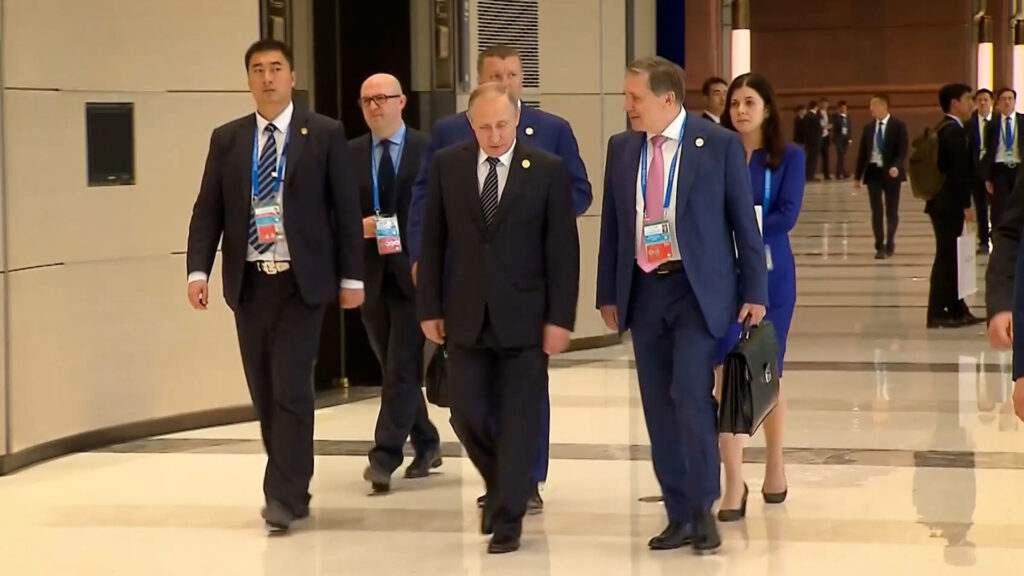

On May 21, 2025, Vladimir Putin personally visited the Kursk Nuclear Power Plant in Kurchatov. That same day, Rosatom’s head, Alexey Likhachev, addressed the Federation Council, touting Russia’s ability to export “sovereignty” to friendly nations. By this, he meant the construction of nuclear power plants (including small-scale reactors), nuclear technology centers, and training hubs for foreign specialists.

However, this claim starkly contrasts with Rosatom’s actual technological capacity. Investigative reports surrounding Rosatom’s contract performance highlight a pattern of technological backwardness and desperation to acquire Chinese nuclear technologies—even by involving third-party countries.One revealing example came on January 4, 2025, when Likhachev told Rossiya-24 that Rosatom plans to sue Siemens for failing to deliver equipment for Turkey’s Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant—an implicit admission of Russia’s growing technological and financial dependence on foreign vendors.

More on this story: Moscow sets the stage for intelligence infiltration into OSCE PA

More on this story: Russian intelligence cover structures abroad