In its ongoing effort to choke off the Kremlin’s war machine, the European Union has levied unprecedented sanctions on Russia. But far from Brussels, a new triangle is quietly forming on the EU’s eastern periphery: Budapest–Astana–Tashkent. This emerging axis—anchored by Hungary’s deepening economic ties with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan—presents not just opportunities for trade and investment, but potential loopholes for Russian interests to sidestep Western restrictions. In the two parts of our report, we uncover the growing alignment of these nations — and expose the networks quietly eroding the sanctions regime.

Hungary’s “Eastern Opening”: Strategic Outreach to Central Asia

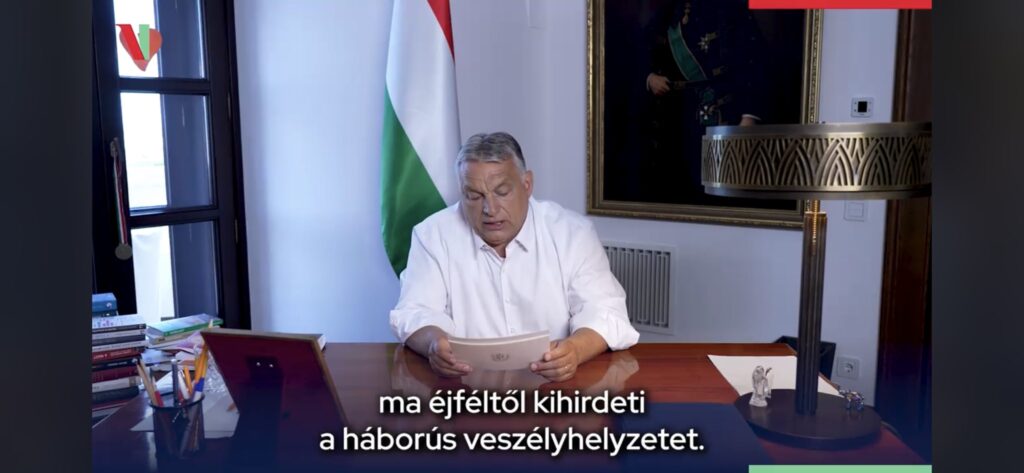

On November 24, 2023, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán stood alongside Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev in the ornate halls of Akorda Palace and pledged to boost bilateral trade to $1 billion. The gesture, made as war still raged in Ukraine, underscored Orbán’s refusal to let the conflict disrupt Hungary’s growing ambitions in Central Asia.

Budapest’s outreach is not new, but its momentum has surged. Hungary was the first European country to recognize Uzbekistan’s independence in 1991, and in 2021 the two signed a strategic partnership agreement. Since Orbán’s government adopted its “Eastern Opening” policy, trade with Uzbekistan has quadrupled—two-thirds of that growth occurring over the past five years. Between 2018 and 2023, Hungarian-Uzbek trade tripled. A similar trend is visible with Kazakhstan: in 2022, trade rose nearly 20%, topping $200 million in 2023.

While still modest in scale—Hungary’s total exports in 2024 are projected at $167 billion—the pace of expansion is striking. Hungarian exports to Kazakhstan grew from $120 million in 2018 to $264.5 million in 2024. The economic footprint is expanding in tandem: Hungary has poured more than $370 million into Kazakhstan’s economy and nearly $500 million into Uzbekistan’s. Over 70 Hungarian enterprises now operate in Kazakhstan, mainly in machinery, agriculture, and logistics—with over $540 million in joint projects under development.

In Uzbekistan, Hungary’s OTP Bank acquired a 73.7% stake in Ipoteka Bank, the country’s fifth-largest lender, securing a critical financial foothold. Combined investments by Hungarian heavyweights—OTP, pharmaceutical firm Gedeon Richter, agribusiness Bonafarm—now approach $500 million.

Economic Alliances with Political Overtones

Behind the trade figures lies a growing web of institutional and strategic frameworks:

- A joint Kazakh-Hungarian investment fund was launched in 2023.

- A Central Asian Direct Investment Fund (CADIF), initiated by Hungary, saw its contribution tripled to $150 million in 2024, signaling Budapest’s commitment to long-term infrastructure and industrial projects.

- In May 2024, a 50-hectare industrial zone in Tashkent was greenlit for Hungarian and European businesses, envisioned as a springboard for regional investment.

Hungarian state-owned developer Inpark—known for managing 17 industrial parks back home—is negotiating terms with Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Investment. These efforts aim to replicate Inpark’s success in attracting global firms like Airbus and Bosch to Hungary, now in the heart of Central Asia.

Meanwhile, Hungary’s MOL Group is investing $192 million into gas extraction at Kazakhstan’s Rozhkovskoye field, with ambitions to produce 1 billion cubic meters annually. Hungary has also expressed interest in Central Asia’s nuclear energy landscape. Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó offered Hungarian training and cooling technology for Uzbek nuclear specialists—should Tashkent proceed with its proposed deal with Russia’s Rosatom.In effect, Hungary is poised to serve as a technical enabler of Russia’s controversial nuclear expansion in the region.

More on this story: Russia Exploits the IAEA to Steal Chinese Nuclear Technology

A New Eurasian Supply Chain—Bypassing Russia

Hungary’s strategic posture goes beyond commodities. It seeks a pivotal role in new East-West trade corridors. A memorandum between Kazakhstan’s KTZ Express, Hungary’s L.A.C. Holding, and China’s Xi’an International Port outlines cooperation on the Trans-Caspian corridor—a trade route that bypasses Russia, linking China, Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, the Caucasus, and eventually the Black Sea and EU markets. Estimated cargo flow could reach 10 million tons annually in the mid-term.

Hungary is also investing in logistics modernization, signing a digital infrastructure deal with Kazakhstan and launching direct Budapest–Tashkent flights in June 2024 to facilitate business exchanges.

Orbán frequently emphasizes Hungary’s “special mission” as a bridge between East and West. His government has cultivated investment ties with Beijing, maintained warm relations with Ankara, Baku, and Astana, and championed cultural kinship with Turkic nations. Hungary even holds observer status in the Organization of Turkic States alongside Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Strategic Hedging—or Dangerous Defiance?

For Orbán, deepening ties with Moscow, Beijing, and Central Asia represent a form of geopolitical balancing—one that offers an alternative to what he perceives as EU overreach. Yet as Hungary drifts further east, its calculus risks attracting scrutiny—or worse, sanctions—from its Western allies.

More on this story: Hungary’s Balancing Act: Strategic Risks of Budapest’s Covert Ties with Russia

The economic logic behind Hungary’s Central Asia pivot is evident. But so too are the geopolitical implications. As EU sanctions attempt to isolate Russia, Budapest’s partnerships with countries like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan—where Russian commercial interests remain robust—could inadvertently offer Moscow new lifelines.The “Budapest–Astana–Tashkent triangle” may not be anti-European by design. Yet in practice, it is creating parallel economic architectures that threaten to blunt the edge of Western pressure.The risk is that Hungary, in pursuit of its sovereign economic strategy, ends up enabling exactly the forces the EU seeks to contain.