Despite their strategic “no limits” partnership, intelligence leaks show deep mistrust between Moscow and Beijing. A recent New York Times–cited report revealed internal Russian warnings that Chinese intelligence is actively targeting Russian military and technological secrets—signaling a shift from cooperation to covert rivalry.

II. Recent NYT Leak: What Russia Fears

- Internal FSB/SVR Assessments label China “the enemy”—accused of recruiting Russian scientists, especially those disillusioned with NATO involvement.

- Key targets: military-tech, Arctic research, and dual-use technologies.

- Espionage methods: using business fronts (mining/academic exchanges) to conceal intelligence activities.

- Document leak by ARES—a cyber-leak and ransomware-linked group—validates Russian intelligence concerns.

III. Historical and Ongoing Espionage Cases

A. Technological Leakage: TsNIIMash-Export (2005–2007)

Five Russian space scientists convicted for selling missile- and space-related research to Chinese counterparts (All-China Precision Engineering.

B. Chinese Industrial Espionage Globally

The Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS) has executed numerous campaigns—APT10, APT40, APT41—stealing cutting-edge tech globally via cyber intrusions and recruiting via LinkedIn.

More on this story: Russia Exploits the IAEA to Steal Chinese Nuclear Technology

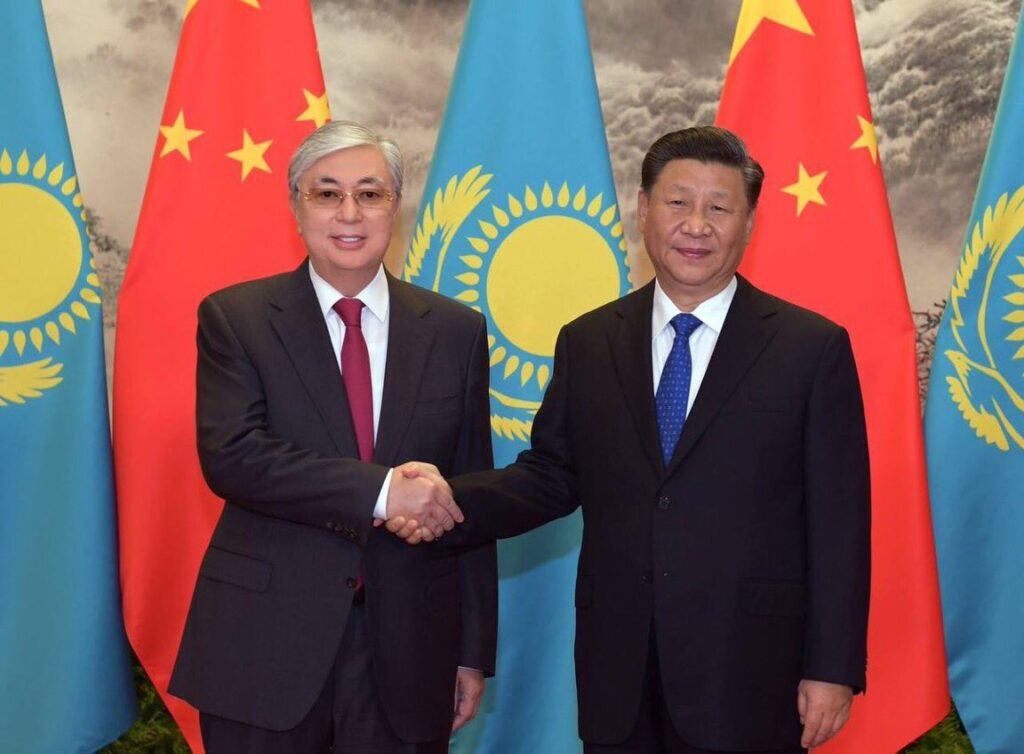

More on this story: Kazakhstan’s Uranium Deal with China: Strategic Gains and Hidden Risks

C. Cross-Targeting Russia

IV. Intelligence Agencies and Methods Involved

| Country | Agency | Known Operations |

| Russia | SVR & FSB | Counterespionage vs China; domestic recruitment monitoring; Arctic-sector NYT leak |

| GRU Units 26165, 29155 | Cyber attacks and sabotage in the West; less active against China | |

| China | MSS | Technological espionage via cyber (APT groups), academic/business espionage; recruitment of engineers |

| PLA Cyber Units | Complement MSS in stealing industrial secrets | |

| Private/Criminal Proxies | APT41, cyber-criminal contractors | Assist Chinese MSS; leaks like GhostNet show long-range reach. |

V. Intelligence Issues and Mutual Mistrust

- Technological race: China covets advanced Russian defense tech; Russia fears being outpaced or out-leveraged.

- Arctic geopolitics: Chinese access to Arctic scientific research heightens Kremlin’s suspicion.

- Covert recruitment: Scholars and engineers are prime recruitment targets—short-term visas mask longer-term intelligence ambitions.

- Cyber spillover: Tools and malware are shared and reused across Russian, Chinese, and global cyber operations.

VI. Strategic and Political Implications

- Eroding the “Axis”: Espionage undermines political and military cooperation, injecting deep mistrust.

- Arms race acceleration: Both nations push ahead on AI, hypersonics, and cybersecurity to outpace their partner-rival.

- Allied reactions: Western agencies can exploit these tensions for deeper intelligence penetration into both states.

- Alliance instability: Growing friction may unravel unified Sino-Russian strategic messaging.

VII. Policy Recommendations

- For Western Governments:

- Exploit Sino-Russian friction to enhance intelligence gathering and technological leakage tracking.

- Strengthen export controls and vetting around exchanges with Russian institutions.

- Support cybersecurity defenses in Arctic and Central Asian research centers vulnerable to Chinese espionage.

- For Intelligence Agencies:

- Monitor short-term scholar/engineer exchanges as espionage vulnerabilities.

- Track technological “bridging” routes—China may leverage third-country fronts (mining/academic) to penetrate Russian research.

- Use OSINT and leak monitoring (like ARES) to expose intelligence rivalries.

The New York Times‑referenced leak highlights a new chapter in Sino-Russian relations: espionage-driven mistrust beneath the veneer of strategic partnership. As each side scrambles to steal edge without letting the other catch up, the uneasy alliance threatens to fracture. Western policymakers and intelligence services should seize this fissure—not just to fortify their own security posture, but to sow division between two of the most assertive authoritarian states on the global stage. Military-Technology Espionage Between Russia and China

Despite their growing diplomatic and military coordination—particularly in the context of the war in Ukraine and joint naval exercises—the Russian and Chinese intelligence services are increasingly locked in a covert struggle for military technological superiority. Both sides seek to gain strategic leverage through clandestine acquisition of sensitive technologies.

1. Russian Military Technologies Targeted by Chinese Intelligence

A. Advanced Missile Systems

- S-400 and S-500 air defense systems have been a major area of concern. China legally acquired the S-400, but intelligence leaks show Beijing tried to reverse-engineer components and obtain performance data beyond what was contractually transferred.

- Chinese cyber units and MSS-linked operatives have reportedly sought classified information about target-tracking radars and electronic warfare modules embedded in Russian platforms.

B. Hypersonic Technology

- Russia’s Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle and Tsirkon missiles are of high interest to the Chinese PLA, which is struggling to match Russia’s field-tested designs.

- FSB reports from the ARES leak describe attempted Chinese infiltration of institutes working on aerothermal coatings, guidance systems, and propulsion technology for hypersonics.

C. Submarine & Underwater Systems

- Chinese MSS is reportedly targeting engineers from the Rubin Design Bureau, which develops Russia’s most advanced nuclear and diesel-electric submarines.

- FSB counterintelligence believes Chinese operatives have sought acoustic signatures, quieting technology, and sonar masking capabilities.

D. Electronic Warfare (EW) and Radar Tech

- China has made repeated efforts to gather intelligence on Krasukha and Murmansk-BN EW systems—key to Russia’s dominance in jamming NATO and Ukrainian platforms.

- MSS attempts have included cyber infiltration of subcontractors, plant visits disguised as technical exchanges, and recruitment of retired engineers.

2. Espionage Techniques Used

| Technique | Description | Notable Incidents |

| Academic Exchange Fronts | Visiting scholar programs used to extract or coerce sensitive info. | Suspected MSS-linked PhDs in Novosibirsk and St. Petersburg aerospace institutes (2022–2024). |

| Cyber Intrusions | APT41 and other PLA-linked units target Russian defense firms. | Targeting of United Engine Corporation and Kalashnikov Concern. |

| Recruitment via Chinese Firms | Business offers to Russian scientists with financial pressure or blackmail. | “Shenyang Aerospace Consulting” and “Chengdu Research Group” flagged by FSB. |

| Joint Ventures as Intel Covers | Bilateral tech companies used to probe and extract military IP. | JV in Yekaterinburg’s metallurgy sector flagged in 2023 for unauthorized tech transfer. |

3. Russia’s Intelligence Response

- The FSB and SVR have intensified counterintelligence surveillance of Chinese nationals, especially in academic and R&D settings.

- A classified circular issued in 2024 warned against “academic and commercial interactions” with over 50 Chinese firms and 12 research institutions believed to have links with the PLA or MSS.

- Export controls tightened: Russia now imposes extra restrictions on defense scientists’ travel to China, especially those in hypersonics, stealth, and radar research.

4. Implications for Strategic Stability

- Mutual Distrust: The Kremlin sees Chinese interest in Russian defense tech not as partnership but as predatory—in line with broader Chinese ambitions to overtake Russia in arms development.

- Unstable Alliance: The very sectors that fuel strategic cooperation (missiles, EW, aircraft) are now sources of friction and backdoor rivalry.

- Impact on Third Countries: China’s adaptation of Russian tech (e.g. radar systems, EW suites) has allowed it to compete with Russian arms exports in markets like Africa and Southeast Asia.

- Potential Russian Retaliation: Moscow may begin feeding disinformation into its academic and tech networks—using fake tech specs or honeytraps to monitor and counter Chinese intelligence.

5. Case Study: The UEC-Saturn Incident (2023)

In late 2023, internal audits at UEC-Saturn—a Russian manufacturer of jet engines—discovered unusual data access by Chinese interns. One was linked to an MSS tech transfer front. Among the accessed files were:

- Blueprints of AL-31F turbofan variants

- Classified performance reports from Syrian and Ukrainian battlefield testing

- R&D data for next-gen vector-thrust nozzles

The FSB intervened, and several Chinese nationals were quietly deported. But the incident deepened security paranoia in Moscow.

Military-technical espionage is fast becoming the most dangerous fault line in the Sino-Russian relationship. While their official discourse remains cooperative, the clandestine competition for strategic military advantages is intensifying. Beijing sees Russian tech as a shortcut to parity with the U.S., while Moscow sees Chinese espionage as a betrayal of trust. The result is an unstable alliance veiled in secrecy and suspicion—an opening that Western intelligence may be able to exploit.

IX. Chinese Political Espionage Targeting Russia

2. Political Intelligence Gathering

: Chinese operatives have reportedly sought to cultivate contacts within the Russian political apparatus—ministries, regional administrations, and even National Guard (Rosgvardiya)—by offering short‑term consulting roles and financial incentives.

- Text-Level Interception: Beijing-linked hackers have infiltrated internal emails and messaging systems belonging to regional officials. These operations gather intelligence on Kremlin policies and internal dissent.

3. Diaspora and Grassroots Tapping

- Monitoring Chinese Nationals in Russia: Educational, family, and business ties provide Beijing with channels to shield surveillance and pressure tactics—tracking diaspora communities to shape Russian political or economic.

- Use of Front Organizations: Similar to the historical “Chinese-Lenin School” model in the USSR (now defunct), modern Chinese consulates and cultural centers in cities such as Vladivostok and Khabarovsk are suspected of dual functions—cultural outreach and political whitelisting .

4. Cyber Espionage Aligned with Political Aims

- Groups such as APT31 (“Judgment Panda”) and TA428—tied to provincial State Security Departments—have conducted intrusions into Russian energy firms, aerospace, and regional government agencies.

- These campaigns blur classical distinctions between economic and political espionage, targeting officials’ communications to extract policy signals or track political dissent.

5. Strategic Rationale Behind Targeting Russia Politically

- Policy Leverage: Gaining insight into internal Kremlin debates gives China a bargaining edge—shaping Russia’s stance on Taiwan, Arctic exploration, trade, and security coordination.

- Risk Mitigation: Knowledge of Russian domestic fractures allows Beijing to mitigate destabilizing actions—such as ensuring Moscow stays aligned with China during crises.

- Hybrid Warfare Readiness: Information on Russian grief or unrest helps China calibrate its geopolitical messaging—as seen in Ukraine, Hong Kong, or Xinjiang policy discourse.

Case Study: Russian Diplomatic Data Breach (2023)

In late 2023, an APT31 intrusion into regional governments in Yekaterinburg and Vladivostok unearthed internal communiqués regarding pipeline deals, Sino-Russian border projects, and local opposition movements. Access to these files allowed Beijing to adjust funding priorities and shape elite loyalty .

Implications

- Alliance Strain: Russian leaders are increasingly suspicious, shifting from silent tolerance to covert counterintelligence operations against Chinese targets.

- Politico-Strategic Uncertainty: As espionage intensifies, both Beijing and Moscow may balk at deeper integration—especially if the theft of sensitive policy intelligence continues.

- Opportunity for the West: These nascent ruptures in the Sino-Russian intelligence axis offer potential openings for Western strategic intelligence and diplomatic initiatives.

Chinese political espionage in Russia operates at the intersection of cyber intrusion and human intelligence, targeting regional officials, diaspora communities, and political actors to gain influence over Kremlin decisions.The uptick in such activity signals a fundamental rift in the Sino-Russian partnership—driven by Beijing’s ambition to control its eastern ally’s internal trajectory. Moscow’s growing backlash indicates these fissures may soon open, with significant geopolitical reverberations.

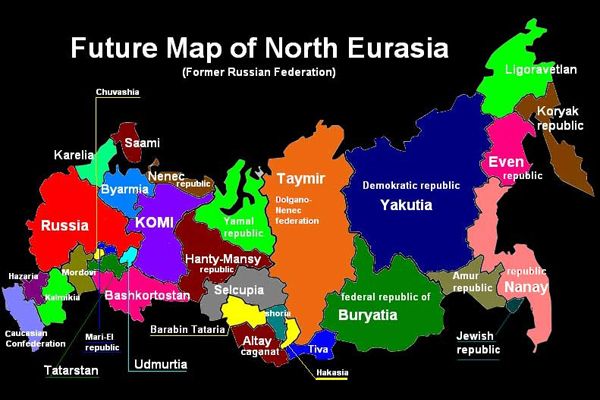

The probability that China will formally attempt to reclaim territories lost to Russia in the early 20th century (such as parts of the Russian Far East, including Vladivostok, Outer Manchuria, or areas around Lake Baikal) remains very low in the near term—but not zero.

1. Historical Background

China lost significant territory to Imperial Russia through so-called “Unequal Treaties”:

- Treaty of Aigun (1858) and Treaty of Peking (1860): Russia gained Outer Manchuria, including Vladivostok, the Amur region, and Primorsky Krai.

- These treaties are still remembered in China as humiliating national losses, part of the “Century of Humiliation.”

2. Current Chinese Strategy: No Formal Claims — Yet

A. Official Position

- China currently does not formally claim these territories, having settled most disputes in bilateral agreements (e.g., 2001 China-Russia Treaty of Good Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation).

- Beijing emphasizes stability and economic cooperation with Moscow, especially amid shared competition with the U.S.

B. Informal Nationalist Pressure

- On Chinese social media and in certain intellectual circles, there are growing discussions about “reclaiming” Vladivostok (referred to in Mandarin as “Haishenwai”).

- Government-affiliated maps and museum exhibits sometimes include these regions as historically Chinese, subtly legitimizing latent claims.

3. Underlying Risks and Trends

A. Demographic and Economic Expansion

- Chinese migration into Russia’s Far East is increasing. Many towns in Primorye and Amur oblasts rely on Chinese businesses, labor, and trade.

- If Russia weakens further due to war, economic collapse, or internal unrest, China could use soft power and economic control to increase its influence or even push for autonomy-style arrangements in these regions.

B. Strategic Patience Doctrine

- China historically waits for favorable conditions to reclaim disputed territories (e.g., Hong Kong, Taiwan in theory, South China Sea).

- If Russia significantly declines militarily or diplomatically, China may consider a “geographic revisionism” strategy, presenting historical claims masked as economic or administrative re-alignments.

4. Russian Countermeasures and Fragility

- Russia is aware of this risk. Recent FSB leaks show Moscow increasing surveillance of Chinese nationals and quietly reinforcing its military presence in the Far East.

- However, the war in Ukraine has drained Russia’s capacity, and its dependence on Beijing has grown sharply—reducing its ability to resist long-term Chinese pressure.

5. Probability Assessment (2025–2040)

| Scenario | Probability | Notes |

| Formal military attempt to retake territory | < 1% | Extremely risky for Beijing; would destroy global image and provoke military conflict. |

| Informal economic annexation or political influence in Far East | 20–30% | Growing possibility, especially if Russian state weakens further. |

| Soft sovereignty claims (e.g., cultural, historic map campaigns) | 40–50% | Already happening subtly. Could intensify if Russia loses global standing. |

| Full Chinese autonomy movements in Russian regions (2030s) | 10–15% | Long-term play. Depends on Russian political fragmentation. |

“How Russia’s Mobilization Weakens Defenses in the Far East and Opens the Door to Chinese Hybrid Operations”

Strategic Background: Russia’s Far East as a Military Buffer

Russia’s Far Eastern Military District (now part of the Eastern Military District, EMD) has traditionally served as a strategic bulwark against potential threats from the Asia-Pacific, including China. Despite official Russo-Chinese friendship, Russian planners have always viewed the PLA’s growing capabilities with caution.

But since 2022, Russia has drastically reallocated combat-ready units, equipment, and logistics from the EMD to support its invasion of Ukraine. This shift has significantly hollowed out the region’s conventional deterrence posture.

2. Mobilization and Military Weakening in the Far East

A. Troop Depletion

- Units from the 35th and 36th Combined Arms Armies, based in the Amur and Transbaikal regions, have suffered heavy losses in Ukraine.

- VDV (airborne) and elite Spetsnaz units from Siberia and the Far East were redeployed west, weakening local reaction capability.

- Training bases, airfields, and even border security forces were stripped of personnel to feed the front.

B. Equipment Drain

- Armored units and modern artillery systems (e.g., T-80, T-90, Iskander missiles) were removed from the Far East and either lost or stuck in long-term refit cycles.

- Eastern units now rely on outdated Soviet-era equipment, making them less capable of defending long and sparsely monitored borders.

C. Loss of Military Readiness

- Reserve call-ups and training resources were directed toward Ukraine, creating an operational vacuum in Eastern Russia.

- The Far East is also experiencing delays in equipment repair and reinforcement due to logistical bottlenecks and sanctions.

3. Opportunities for Chinese Hybrid Operations

A. Espionage and Intelligence Infiltration

- Thinner counterintelligence coverage allows Chinese operatives—both human and cyber—to more easily penetrate strategic sectors, such as:

- Defense factories (Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Vladivostok)

- Railway hubs

- Naval facilities (e.g., Pacific Fleet HQ)

- China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) and PLA Strategic Support Force can exploit degraded FSB capacity in the region.

B. Demographic and Economic Influence Operations

- Chinese businesses and cross-border traders are increasing their foothold in areas like Blagoveshchensk and Khabarovsk.

- “Civilian front” tactics—real estate acquisition, economic dependency, population movement—mirror the early stages of China’s “salami-slicing” strategy used in the South China Sea.

C. Psychological Operations and Information Warfare

- Pro-China narratives are seeping into regional media and online discourse, subtly eroding loyalty to Moscow.

- Rumors of a “better future under Chinese economic leadership” are amplified in areas suffering from neglect and poor infrastructure.

D. Mapping and Infrastructure Projects

- Chinese infrastructure firms involved in joint projects often gain access to sensitive terrain and transport data, potentially dual-use for military purposes.

4. Long-Term Implications

For Russia:

- Sustained weakening of military presence creates a strategic liability in the East, reducing Russia’s multi-front war capacity.

- If relations deteriorate, Moscow could find itself unable to deter Chinese coercion without NATO’s distraction in Europe.

For China:

- Provides a window to increase strategic leverage through soft power and information dominance.

- Sets the stage for long-term erosion of Russian sovereignty in economically valuable and resource-rich regions (e.g., Primorye, Amur).

For the Region and the World:

- Undermines the myth of “multipolar solidarity” between Russia and China.

Offers the U.S., Japan, and India new angles to engage Russia—perhaps even diplomatically—to limit Chinese expansionism.