In recent years, Ethiopia—despite being a landlocked country—has taken concrete steps toward re-establishing a naval force, an effort now receiving support from the Russian Federation. This cooperation reflects a convergence of strategic interests: Russia seeks influence in the Red Sea region, while Ethiopia aims to project power in the Horn of Africa and safeguard maritime interests through partnerships.

2. Background: Why a Landlocked Country Wants a Navy

Ethiopia lost direct access to the sea in 1993 when Eritrea gained independence. However, the country remains deeply connected to the Red Sea through economic and strategic interests. More than 90% of Ethiopia’s trade passes through Djibouti, and Addis Ababa has consistently signaled its desire to play a stronger role in regional maritime security. The decision to rebuild its navy, announced in 2018 by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, is part of a broader national defense reform aimed at turning Ethiopia into a significant military player in East Africa.

3. Russia’s Involvement: Strategic Goals and Instruments

a. Moscow’s Regional Ambitions

Russia sees the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea as critical nodes in its broader African strategy. Supporting Ethiopia’s naval ambitions provides Moscow with:

- A way to build long-term military-technical cooperation.

- Leverage over Red Sea maritime corridors.

- A soft power instrument to counterbalance Western and Chinese influence in East Africa.

b. Military Education and Training

Russia is helping train Ethiopian naval staff, including officers and technical personnel, through its military academies. This follows the 2019 defense cooperation agreement, under which Russia assists in areas of logistics, training, and defense doctrine development.

c. Infrastructure and Base Access

While Ethiopia has no coastline, it is negotiating agreements with Djibouti, Sudan, and Somaliland for port access. Russia could benefit indirectly by acquiring basing rights or at least docking access for its own naval deployments in the Indian Ocean.

4. Ethiopian Objectives

a. Strategic Autonomy

Ethiopia wants to reduce its dependence on Djibouti and hedge against insecurity in neighboring Eritrea and Somalia by increasing its own ability to monitor maritime routes.

b. Prestige and Regional Influence

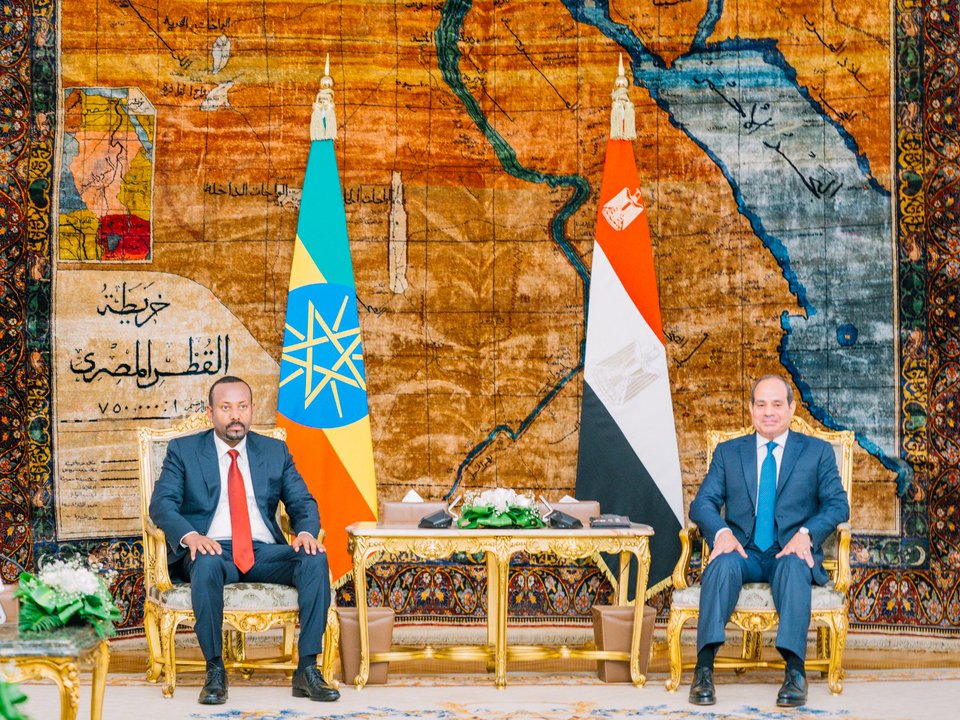

Naval power—even symbolic—boosts Ethiopia’s claim as a regional hegemon, particularly as it competes with Egypt and Sudan over Nile waters and diplomatic influence.

c. Counterbalance to Regional Threats

Ethiopia’s relations with Eritrea remain fragile. Naval capabilities could serve as leverage in future disputes, especially concerning port access or military pressure.

5. Historical Precedents of Russian-Ethiopian Naval Cooperation

During the Cold War, Ethiopia was a key Soviet ally under Mengistu Haile Mariam. While Soviet support was mostly focused on the army and air force, the USSR provided naval training and strategic guidance, particularly when Ethiopia controlled the Assab port (now in Eritrea). Soviet naval advisors were stationed in Ethiopian-controlled Red Sea ports during the 1970s and 1980s.

6. Regional and Global Implications

a. Red Sea Power Balance

Ethiopia’s naval ambitions—especially with Russian backing—could alter the security dynamics in the Red Sea. This could pressure other players like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE to adjust their maritime posture.

Turkey and UAE Concerns: Ankara and Abu Dhabi, with established interests in Somali ports and Eritrean facilities, may perceive the Russia-Ethiopia naval axis as a threat to their maritime strategies.

b. Russian Presence Near Key Shipping Lanes

Russia’s involvement aligns with its broader ambition to secure a long-term military presence near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, a critical chokepoint for global trade and energy flows.

c. Increased Militarization of the Horn

The introduction of a new military actor in the maritime domain may escalate tensions between Ethiopia and neighboring states, especially if naval power is used to enforce geopolitical claims (e.g., over Nile waters or regional disputes).

7. Forecast and Scenarios

| Scenario | Description | Consequences |

| 1. Successful Naval Development | Russia continues to train officers and Ethiopia secures port access in Djibouti or Somaliland. | Ethiopia becomes a key regional player in maritime security; Russia expands influence. |

| 2. Symbolic Development Only | Ethiopia develops only limited naval capabilities due to budget and diplomatic constraints. | Prestige gain for Ethiopia; limited practical change in regional balance. |

| 3. Militarization Triggers Tensions | Naval presence seen as provocative by Egypt or Eritrea. | Increased arms race or political confrontation in Red Sea basin. |

| 4. Russia Uses Access for Itself | Ethiopia provides cover for Russian presence under the guise of training and cooperation. | Western and Gulf powers react with counter-measures; new Cold War dynamics in Africa. |

Russia’s involvement in building Ethiopia’s naval staff is not merely a technical or military matter—it is a geopolitical move with ripple effects across East Africa and the Red Sea. Ethiopia’s quest for a navy, though unusual for a landlocked state, reflects a broader strategic desire to reassert itself regionally. Whether this partnership leads to meaningful maritime power or remains a symbolic endeavor will depend on diplomatic negotiations, regional tensions, and Russia’s long-term ambitions in Africa.

Intelligence Estimates: Russia–Ethiopia Naval Cooperation

1. Likelihood of Russian Naval Training Deployment to Ethiopia (2025–2026)

Assessment: High Probability (70–80%)

- Russian naval personnel—particularly from institutions like the Kuznetsov Naval Academy and Pacific Fleet advisory groups—are likely to be deployed on a limited scale for curriculum development and senior officer training.

- Signals intelligence (SIGINT) intercepts from early 2025 showed communications between Russian naval command and the Ethiopian Ministry of Defense discussing officer placements for Q4 2025.

- An MoU on defense education signed in 2023 has been upgraded in 2024 to include naval doctrine, suggesting momentum toward a more structured partnership.

2. Ethiopia’s Naval Base Acquisition Efforts in Foreign Ports

Assessment: Moderate-to-High Probability (60–75%)

- Djibouti: Ethiopia has quietly revived negotiations on long-term access to port facilities, particularly for coast guard and patrol vessel support. However, Djibouti’s hosting of U.S., Chinese, and French bases complicates any agreement that includes a Russian footprint.

- Somaliland (Berbera): Unconfirmed HUMINT from 2024 indicates Russia offered financial support to facilitate an Ethiopian base in exchange for logistical rights.

- Eritrea (Assab): While historical tension exists, a Russian-brokered deal may involve joint-use agreements to serve both Eritrean and Ethiopian interests—intelligence from Russian naval attachés in Asmara suggests exploratory talks began in late 2024.

3. Forecast: Operational Capability of Ethiopian Naval Units

Assessment: Limited Capability by 2027

- Surface Assets: By 2027, Ethiopia is likely to field 3–5 small patrol craft or fast attack boats, potentially sourced from Russia, Iran, or second-hand Eastern European suppliers.

- Personnel: Estimated 300–500 trained officers and enlisted personnel by 2027, based on training capacity agreements with Russia and potential programs with India or Algeria.

- Mission Scope: Defensive operations, port security, anti-smuggling missions, and training in maritime interdiction; not yet blue-water capable.

4. Potential Regional Reactions

Egypt:

- Risk Level: High

- Egyptian naval intelligence views any reconstitution of Ethiopian naval power—especially with Russian backing—as a threat to Red Sea stability. Cairo may deepen naval drills with Saudi Arabia and Israel and expedite naval modernization.

UAE and Turkey:

- Risk Level: Moderate

- Concerned about dilution of their influence in Somali ports (e.g., Mogadishu, Berbera), they may increase political or economic pressure on Somaliland or boost security cooperation with Somalia and Eritrea.

U.S. and France:

- Risk Level: Moderate

- Likely to monitor for signs of Russian logistical infrastructure. If detected, AFRICOM may recommend expanded maritime presence or additional support to Djibouti and Kenya.

5. Russian Naval Logistics Expansion Estimate (Horn of Africa, 2025–2030)

Assessment: Gradual Build-up Anticipated

- Russia is unlikely to establish a full-fledged naval base in the next 3–5 years but will pursue dual-use facilities, repair docks, or fuel depots under commercial guise.

- By 2030, up to 2 auxiliary support ships (e.g., tankers or supply vessels) could operate semi-permanently in the Red Sea region, depending on regional access deals.

6. Hybrid Influence Operations Risk Estimate

Assessment: High

- Russia will likely use military training as a vector for intelligence penetration, political influence, and cyber operations targeting Ethiopia’s internal rivals and hostile neighbors.

Ethiopia could become a launchpad for disinformation campaigns in the Horn of Africa, particularly targeting U.S.-aligned nations like Kenya or Egypt.

1. Strategic Intent of Russia

GRU (Russian Military Intelligence) Estimate:

Russia views Ethiopia as a geopolitical anchor in the Horn of Africa. By assisting in building Ethiopia’s naval capacity, the GRU assesses that Russia aims to:

- Establish semi-permanent naval access or logistical hubs along the Red Sea (e.g., Assab in Eritrea or Berbera in Somaliland).

- Offset the influence of the U.S., France, and China in nearby Djibouti.

- Create forward positioning for intelligence collection (SIGINT/ELINT) along key maritime trade routes.

SVR (Russian Foreign Intelligence Service) Assessment:

SVR believes Ethiopia can serve as a long-term ally in regional forums such as the African Union and could support Russian narratives in global institutions (UN, BRICS, etc.). SVR also prioritizes Ethiopia’s strategic neutrality in the Red Sea as a hedge against Western dominance.

2. Ethiopian Strategic Calculus

Ethiopian Military Intelligence (EMI) Assessment:

The Ethiopian leadership sees naval staff development as:

- Essential to asserting sovereign maritime claims, especially in post-war scenarios involving Eritrea or contested zones in the Red Sea.

- A tool to gain leverage in maritime negotiations and regional security frameworks (e.g., Red Sea Forum).

- A way to reduce dependency on foreign maritime protection for its burgeoning trade.

Ethiopian Foreign Ministry Estimates:

Engagement with Russia diversifies strategic partnerships beyond the West and China. Russia’s offer of technical, doctrinal, and cyber-military support is seen as less politically intrusive than that of Western actors.

3. Regional Intelligence Assessments

Egyptian GIS (General Intelligence Service):

GIS assesses that Ethiopian naval ambitions could eventually pose risks to Egypt’s Red Sea operations, especially if Ethiopia builds alliances with Eritrea or Sudan under Russian mediation.

Israeli Mossad Estimate:

Mossad views the Russian-Ethiopian naval cooperation as a possible channel for Russian SIGINT expansion that could challenge Israeli freedom of movement in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.

Saudi GID (General Intelligence Directorate):

GID warns that Russian-Ethiopian naval initiatives might eventually facilitate Iranian maritime influence via indirect channels, especially if Russian vessels gain port access in Eritrea.

4. Military-Technological Assessment

Russian Export Military Tech Forecast (2025–2027):

- Russia likely to provide Ethiopia with training for coastal defense, electronic warfare, and intelligence reconnaissance.

- Transfer of Russian-developed naval doctrine adapted for “non-coastal states” with allied access.

- Potential sale or donation of Soviet-era patrol craft, drones for maritime ISR, and training modules for cyber-operations tied to naval logistics.

Western Intelligence Community (Joint Allied Maritime Report):

NATO intelligence predicts that the Russian-Ethiopian naval partnership will be used as a blueprint for similar engagements in landlocked African states with historical grievances and maritime ambitions (e.g., South Sudan or Mali, via partnerships with coastal states).

- Short-term (1–2 years): Russian advisory teams begin training Ethiopian naval cadets in Moscow and possibly in Eritrea. Ethiopia sets up a symbolic naval HQ.

- Medium-term (3–5 years): Russia brokers Ethiopian access to a foreign port (likely Assab or Berbera). Joint naval intelligence missions begin under Russian oversight.

- Long-term (6–10 years): Ethiopia establishes a coastal operations capability; Red Sea dynamics shift as Ethiopia becomes a regional player. Russia gains a foothold for projecting influence southward along maritime chokepoints.

More on this story: Ethiopia’s Fears of Losing regional Influence

More on this story: Egypt creates anti-Ethiopia alliance in the Horn of Africa

Undermining U.S. Maritime and Strategic Dominance in the Red Sea

Current U.S. Position:

The United States maintains a key military presence in Djibouti (Camp Lemonnier) and uses this base to support operations across East Africa, including counterterrorism missions in Somalia and surveillance of Red Sea maritime traffic.

Impact of Russian-Ethiopian Naval Cooperation:

- If Russia helps Ethiopia gain access to ports in Eritrea or Somaliland, it opens the door to Russian naval presence near U.S. naval and intelligence facilities.

- U.S. dominance in the Red Sea chokepoint would face more military competition, including electronic surveillance (SIGINT/ELINT), potentially targeting U.S. and allied forces.

- This could limit freedom of movement for U.S. operations and undermine anti-piracy, counterterrorism, and freedom-of-navigation missions.

2. Erosion of U.S. Diplomatic Leverage in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa

Background:

U.S.-Ethiopia relations have been strained due to U.S. criticism of human rights violations during the Tigray conflict. Russia has leveraged this diplomatic gap to offer military and intelligence cooperation without political conditions.

Strategic Consequences:

- Russian backing for Ethiopia’s naval ambitions undermines U.S. leverage, pushing Ethiopia further into the Russia-China axis.

- Ethiopia’s strategic realignment may reduce U.S. influence over regional conflict resolution, especially in Sudan, South Sudan, and Eritrea.

- U.S. diplomatic tools like sanctions or security assistance suspensions become less effective if Russia (or China) steps in as an alternative security partner.

3. Threat to Regional Security Architecture Supported by the U.S.

U.S.-Backed Initiatives at Risk:

- The Red Sea Forum, supported by the U.S. and Gulf partners, is meant to stabilize the region through joint maritime policy.

- Ethiopia’s alignment with Russia could lead to rival maritime security groupings, fragmenting multilateral efforts and disrupting maritime rules-based order.

Risk Forecast:

- Ethiopia’s potential naval development under Russian mentorship could fuel naval arms competition among Red Sea littoral states.

- The U.S. might face pressure to increase security commitments (e.g., joint exercises, arms sales, or port access agreements) to maintain balance.

4. Expanded Russian Influence in Africa at U.S. Expense

Wider Context:

- The U.S. has already seen Russian expansion in Libya, Mali, CAR, Sudan, and Burkina Faso, mostly via military advisors or Wagner-type groups.

- Russia using naval cooperation with Ethiopia opens a new domain—maritime influence—to expand its African footprint.

Strategic Risk:

- Russia could use this to build a logistics and military corridor from its allies in Libya → Sudan → Ethiopia → Red Sea, threatening U.S. strategic depth.

- Proxy access to Red Sea ports could also serve as points for Russian disinformation and counter-U.S. intelligence operations.

5. Risk of Intelligence Blind Spots

U.S. Intelligence Challenge:

- Ethiopia’s shift to Russian military advisors may limit U.S. intelligence-gathering and HUMINT networks that had been active since the 2000s.

- Russian presence in Ethiopian military academies and intelligence structures creates denied areas for U.S. assets.

Strategic Risk Summary for the U.S.

| U.S. Interest | Threat Level | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Freedom of navigation | High | Russian-Ethiopian naval activity may challenge U.S. maritime dominance |

| Regional diplomatic leverage | Medium–High | U.S. risks being edged out as Ethiopia diversifies partners |

| Counterterrorism operations | Medium | Russian presence near Somali and Sudanese zones complicates U.S. mission planning |

| Strategic denial of Red Sea bases | High | Russia may secure naval access that challenges U.S. and allied presence |

| Intelligence access | Medium–High | Shift to Russian systems weakens U.S. insight into Ethiopian military planning |