Orbán is no longer just a problematic EU member—he has emerged as a direct agent of the Kremlin, wielding bribery and institutions to destabilize the bloc from within. His strategic alignment with Moscow undermines EU solidarity, sanctions policy, and financial security—and demands urgent European scrutiny.

In recent years, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has evolved from a Euroskeptic into a serious threat to the European Union—thanks to opaque deals, selective regulation, and citizenship manipulation. This is not mere diplomatic balancing or populist rhetoric; it is a systematic rollout of shadow financial schemes that undermine the EU’s financial security and its ability to resist foreign interference.

By obstructing anti-corruption reforms and vetoing key EU sanctions on Russian firms, Orbán transformed Hungary into a major conduit for sanctions evasion. He resisted beneficial‑ownership transparency initiatives, blocked anticorruption legislation, and repeatedly delayed sanctions decisions.

Since 2023, investigative journalists have uncovered dozens of shell companies in Hungary that provided logistics and insurance services to Russia’s “shadow fleet.” These opaque entities have ties to Kremlin-linked oligarchs such as Igor Sechin and Gennady Timchenko. OCCRP named lawyer Andrey Mochalin, who issued fraudulent P&I certificates to tankers transporting Russian oil, as well as Artem Kuznetsov, a former FSB operative who facilitated visits by “shadow diplomats” to Budapest to establish banking channels—some under the cover of diplomatic immunity or as part of International Investment Bank (IIB) projects.

More on this story: Hungary’s Balancing Act: Strategic Risks of Budapest’s Covert Ties with Russia

More on this story: Hungary: Trojan Horse in Russia’s Proxy War Against Europe

The Budapest branch of that bank played a central role—and U.S. officials have accused it of being a front for Russian intelligence. Orbán granted its staff diplomatic immunity and blocked financial oversight. Despite warnings from NATO partners, he defended the institution and even lobbied for its expansion. Only after intense diplomatic pressure in 2023 did Hungary agree to shutter the office, relocating its headquarters back to Moscow on April 9, 2024.

Orbán’s “golden visa” scheme, first launched in 2013, enabled thousands—including Russians—to gain Schengen‐area residency via investments in Hungarian government bonds. Operated through offshore intermediaries with minimal vetting, some of these “investments” were reportedly repatriated to Russia or used for sanctions circumvention. Although it was paused in 2017, the program resumed in 2024 under slightly tighter—but still opaque—terms.

Hungarian banks have become key enablers of Russian schemes. Smaller private banks—such as MKB Bank and GránitBank—have opened accounts for sanctioned Russian front companies and individuals, facilitating transactions involving Gazprom and political actors in Serbia and Bosnia aligned with anti-Western ideologies.

Even OTP Bank, Hungary’s largest financial institution with subsidiaries across Eastern and Central Europe, has been implicated. While not directly orchestrating illicit transactions, OTP serves as a vital “infrastructure provider” in gray‑zone services to high‑risk clients from Russia, Azerbaijan, and Central Asia. Its Russian arm remained operational after most foreign banks exited post‑February 2022. According to The Financial Times, OTP was among the top seven foreign banks paying taxes in Russia in 2023.

Although 2024 tax figures are not yet available, OTP Group’s annual report states that its Russian subsidiary increased profits by over 40%, reaching 137 billion forints (≈ $372 million)—more than 11% of the group’s total. Reuters notes that this is a significant share, especially given EU and U.S. sanctions. OTP insists it complies with rules, has ceased corporate lending, avoids dollar-denominated transactions, and applies EU-standard security for euro payments.

Yet OTP’s operations in authoritarian Russia come with serious risks. Under Moscow’s laws, banks must cooperate with the FSB and provide personal data of clients. This places hundreds of thousands of EU citizens at risk of data exposure, violating GDPR and opening the door to manipulation or blackmail—especially among politicians, journalists, or activists.

Moreover, part of OTP’s Russian IT infrastructure is integrated with local regulatory systems. This allows security services to monitor transactions and gain potential backdoor access to data from other OTP branches. A successful hack—or insider infiltration—could expose financial records of EU citizens, threaten electoral integrity, and even destabilize the EU’s financial network.

OTP’s subsidiaries in the Western Balkans offer Russia yet another foothold. These branches can indirectly finance pro‑Kremlin political groups, manipulate loan schemes, or launder funds—posing a direct threat to regional stability.

Despite repeated ECB warnings, Hungary’s central bank has shown no inclination to investigate OTP’s Russian ties. But if OTP remains entwined with Kremlin sanctions circumvention, Europe’s financial security is at stake. The EBA and ECB must scrutinize OTP as a conduit for Russian interference.

Investigations by Hungary’s Direkt36 revealed that OTP’s Hungarian unit also handled funds tied to Azerbaijan’s president Aliyev’s family, using networks based in Turkey and the UAE—potentially bypassing FATF and AMLD checks.

Orbán has effectively monetized EU membership, trading Brussels’ trust for energy preferences and foreign capital—showing the success of autocracy paired with systemic corruption, even within a formally Western political framework.

That same network helped facilitate Andrey Naryshkin’s son—the intelligence chief’s child—gaining Hungarian residency via an investment firm linked to Orbán’s personal doctor and political insiders.

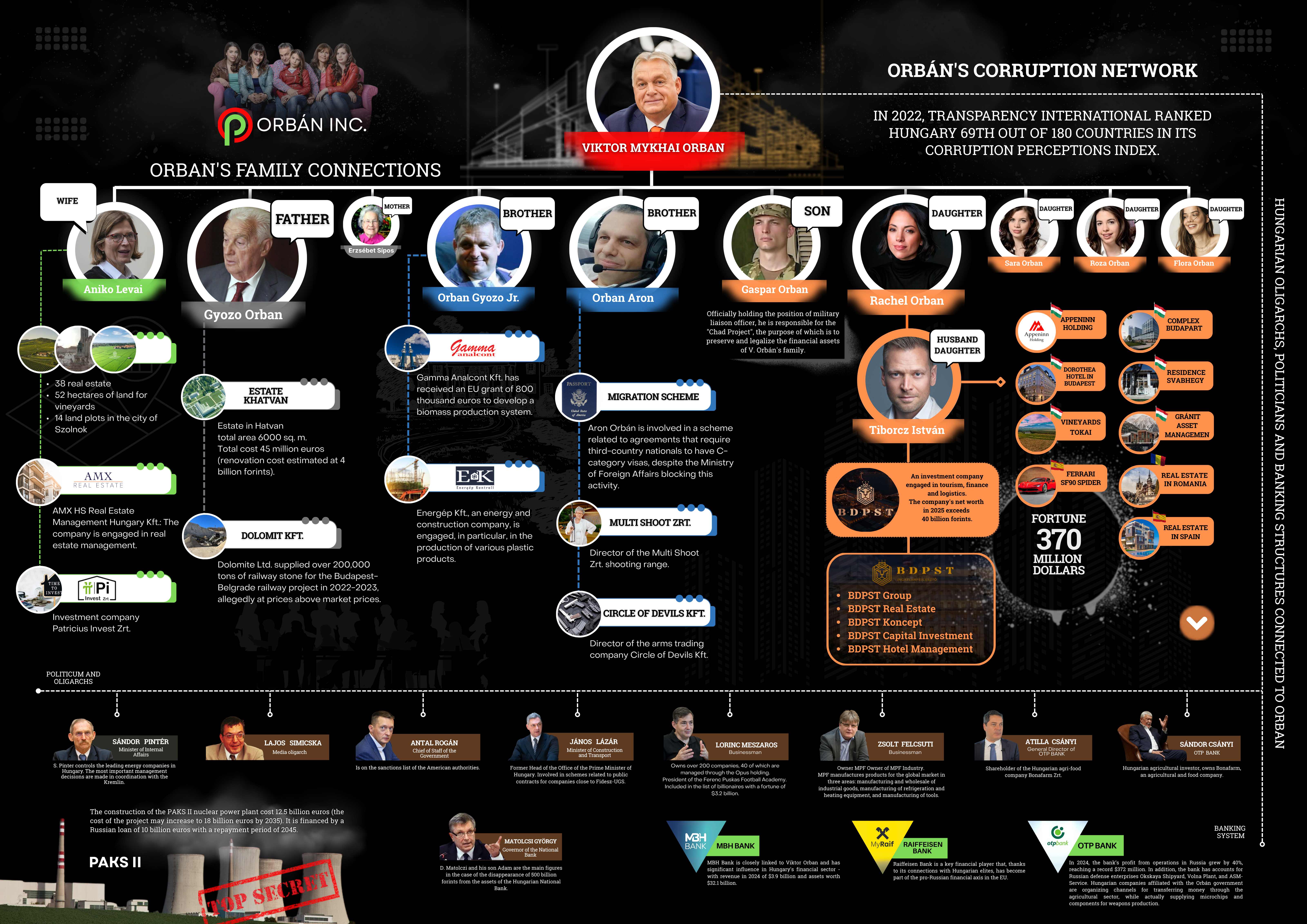

Orbán’s family also benefits directly from state largesse. His centimillion‑euro empire spans Croatia, Spain, Serbia, and Romania—much of it amassed via alleged corruption. Son‑in‑law István Tiborcz faced five EU anti‑fraud investigations (OLAF) over misuse of funds, nepotistic contracts in street‑lighting projects, forestry subsidies, and real‑estate developments.

Tiborcz’s firm Dorothea Hotel received €105 million in preferential loans; his Nova Belgrade complex spans more than 122,000 m². Orbán’s brother and father—both named Győző—profit from construction and quarry contracts tied to state tenders and EU funds.

Viktor Orbán directly green‑lit Russia‑backed projects such as the Paks II nuclear plant—subject to a €12.5 billion deal financed 80% by Russia. The contract bypassed transparent procurement and remains secret for 30 years.

Project lobbyist Klaus Mangold, nicknamed “Mr. Russia,” brokered key meetings and financing. Despite warnings, Hungary issued Rosatom a license in August 2022. A series of safety issues and project delays sparked environmental and transparency protests from Greenpeace, Transparency International, and domestic opposition parties through 2025.

Orbán’s consolidation of power has facilitated a kleptocratic political‑economic alliance enriched by pro‑Russian business elites. Oligarchs like Lőrinc Mészáros and Sándor Csányi dominate public works, agriculture, and fertilizer imports, often displacing competitors and reversing sanctions against Russian producers. The fallout includes forced bankruptcies (like Nitrogénművek Zrt) and alleged corporate favoritism.

These graft‑driven networks steer billions in highway concessions—via MKIF Zrt—and obscure rail tenders linking Budapest, Egypt, and Moscow—all under apparent oversight by Orbán allies. Subsequent public‑procurement investigations highlight serious accountability failures.

Orbán’s 2023 “Chad Initiative” saw Hungary sign secret military agreements, deploy armed forces, and invest $200 million in Sahel agriculture—all in exchange for uranium access and as an asset‑protection mechanism for the Orbán family.

More on this story: Hungary is setting closer cooperation with Russia in Chad

More on this story: Hungary’s Shadow Play in Chad: The Orbán Doctrine Enters Africa

Simultaneously, Hungary’s Eximbank issued millions in politically motivated loans: €10.6 million to Marine Le Pen in 2022 and €9.1 million to Spain’s VOX in 2023. Orbán leveraged these loans to weaken EU unity by threatening vetoes unless key Russian oligarchs—such as Mikhail Friedman and Vyacheslav Moshe Kantor—were delisted from sanctions. By blocking EU sanctions, Orbán acted as a Kremlin agent within Europe.

Bellingcat and OCCRP investigations show that Orbán’s patronage enabled OTP to conduct euro-clearing operations for Russian banks via shell firms in Austria, Dubai, and Cyprus. His willingness to bypass EU institutional norms—often backed by Kremlin-linked bankers—makes Hungary, effectively, a de facto Russian ally within the EU.

In 2024, Transparency International ranked Hungary as the most corrupt EU country. Over €20 billion in EU funding has been frozen due to systemic corruption—but Orbán continues to resist sanctions enforcement and deepen ties with Moscow.

More on this story: How Hungary’s Outreach to Central Asia Risks Undermining EU Sanctions on Russia

More on this story: Viktor Orbán’s Russian Alignment: A Threat from Within the European Union”

More on this story: Budapest Establishes Infiltration Channel for Russian Intelligence