The killing of local civilians by the Russian Wagner Group near a gold mine in the Central African Republic (CAR) has reignited international scrutiny over Moscow’s extractive activities in Africa. While Russian officials deny involvement, testimonies and satellite evidence suggest Wagner’s direct responsibility. This incident is part of a broader pattern of violence and coercion tied to Russia’s expanding grip over African mineral resources—mirroring past abuses in Zimbabwe and raising questions about rising local resentment and the risk of anti-Russian uprisings.

2. Incident Overview: Wagner’s Atrocities at CAR Gold Mines

In mid-2025, local reports and humanitarian organizations confirmed that Wagner personnel executed dozens of civilians in the Ndassima area—an artisanal gold mining region long plagued by violence. Witnesses claim Wagner fighters accused locals of “unauthorized prospecting” and collaboration with rebel groups. The operation reportedly included house-to-house raids, mass detentions, and executions—aimed at clearing the area for industrial exploitation.

This is not an isolated event. Since 2018, Wagner has acted as a de facto security and extraction force in CAR, securing strategic assets in exchange for access to gold, diamonds, and timber.

3. Motivations Behind Wagner’s Use of Violence

a. Resource Consolidation

Wagner’s primary goal is to monopolize artisanal mining zones and convert them into high-yield, Russian-controlled concessions. Violence is used to:

- Intimidate or eliminate local competition;

- Deter collaboration with rival groups or Western interests;

- Establish full logistical control over mining routes.

b. Political Leverage and Regime Protection

Wagner operates under bilateral security agreements with CAR’s President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, providing protection in exchange for economic privileges. The massacre is likely part of a wider strategy of militarized governance, deterring opposition by terrorizing civilians in contested regions.

c. Disruption of Rebel Supply Chains

Some CAR rebel groups fund themselves through artisanal mining. Wagner uses brutal tactics to disrupt rebel resource flows, often targeting civilians suspected of indirect collaboration.

4. Comparative Case: Zimbabwe’s Marange Diamond Fields

The events in CAR resemble the 2008 Marange diamond killings in Zimbabwe, when the military—backed by Chinese and private partners—killed over 200 artisanal miners to clear the area for state-run extraction. Parallels include:

- Use of foreign security partners to consolidate elite control over mines;

- Extreme force to remove informal miners;

- Exploitation of natural resources as a geopolitical bargaining chip.

Like in Zimbabwe, Russian operations in CAR blend military repression with commercial exploitation, operating in a legal vacuum where foreign mercenaries replace formal state institutions.

5. Russian Mining Control in Central Africa

Russia, through Wagner and affiliated shell companies, controls or influences:

- Ndassima gold mine (CAR) – jointly exploited by Midas Ressources, a front for Wagner.

- Bria and Bambari gold fields – heavily militarized zones where locals report restricted access.

- Diamond mines in Haute-Kotto prefecture – guarded by Wagner personnel, integrated into transnational smuggling networks.

- Timber and rare earths – secondary sectors, often bundled into logistical supply chains tied to Wagner security corridors.

These assets are part of a broader strategy to finance Russian foreign operations without traceable state funds, making Africa both an economic and strategic theater.

6. Local Sentiment Toward Russian Presence

Initially, Wagner was welcomed by some CAR citizens for pushing back against rebel groups, but sentiment has soured due to:

- Civilian deaths and repression of artisanal miners;

- Unpaid wages and abuses reported by local recruits working under Wagner;

- Growing authoritarianism under Touadéra, linked to Russian backing;

- Rising cost of living and restricted access to traditional livelihoods, especially in areas militarized for Russian extraction.

Surveys by NGOs and local church networks show a growing disconnect between public support for Russia and elite dependence on it.

7. Probability of Anti-Russian Riots and Civil Unrest

The risk of anti-Russian riots or uprisings in CAR and the region is growing due to several converging factors:

a. Grassroots Rage and Economic Displacement

- Thousands of locals depend on artisanal mining. Their violent displacement by Wagner has created widespread resentment.

- As economic alternatives shrink, tensions rise—especially among youth and ex-rebels who feel betrayed by the government and foreign actors.

b. Ethnic and Political Undercurrents

- Wagner’s brutality disproportionately affects certain ethnic groups, creating ethno-political grievances.

- Opposition groups may capitalize on this sentiment, framing Russia as a neo-colonial force.

c. External Agitation and Regional Spillover

- Western and African powers wary of Russia’s growing influence may indirectly support anti-Russian narratives.

- CAR’s instability risks spilling over into Chad, Cameroon, and Sudan, where Russian-linked mining firms have growing footprints.

d. Precedent of Riots Against Foreign Forces

- In 2022–2023, Mali and Burkina Faso saw localized riots against foreign bases. CAR’s urban centers could erupt similarly, especially if another high-casualty event occurs.

Estimated Probability of Anti-Russian Riots in CAR (2025–2026): 65–75%, with hotspots in Bangui, Bria, and Bambari.

8. Conclusion

The Wagner Group’s killing of civilians in the Central African Republic is not an isolated atrocity but part of a systematic pattern of violence to secure Russian resource dominance in Africa. The comparison with Zimbabwe’s Marange massacre reveals the cyclical nature of foreign-backed repression in extractive economies. As local anger grows and livelihoods are destroyed, the likelihood of anti-Russian unrest increases, posing risks to both regional stability and Russia’s strategic ambitions in Africa.

Russia, primarily through the Wagner Group and affiliated shell companies, is extracting a range of valuable natural resources in Africa, often under murky contracts with fragile or authoritarian regimes. The goal is to secure income streams independent of formal Russian state budgets, bypassing sanctions and funding operations abroad. Below is a breakdown by resource type and country:

Gold

- Central African Republic (CAR)

- Ndassima Gold Mine: One of the most important gold sites in CAR. Controlled by Midas Ressources, a front company for Wagner. Locals have been violently expelled.

- Bria, Bambari regions: Gold fields militarized by Wagner, where artisanal mining is banned or forcibly cleared.

- Sudan

- Wagner-linked companies (e.g., Meroe Gold, tied to Russia’s Lobaye Invest) operate semi-officially in conflict zones like Darfur and South Kordofan.

- Smuggling networks are used to bypass Sudanese authorities and move gold to Russia via Dubai or Syria.

- Mali

- Since 2022, Wagner has expanded into gold-rich regions like Kayes and Sikasso, using shell companies in joint ventures with Malian authorities.

Diamonds

- Central African Republic

- Wagner operates in the diamond-rich Haute-Kotto region and controls local trade networks via intimidation and military checkpoints.

- Artisanal miners are coerced into selling at artificially low prices through Wagner intermediaries.

- Possibly Guinea and DRC

- There are unconfirmed reports of Wagner exploring involvement in alluvial diamond mining in these countries via local proxies.

Timber

- Central African Republic

- Wagner has established control over timber concessions in the Lobaye and Sangha regions, harvesting exotic hardwoods (like sapele and ayous) for export.

- These operations often involve illegal logging in protected zones, and profits are allegedly funneled through shell companies in Cameroon.

Rare Earths and Strategic Minerals

- Madagascar

- Wagner-linked firms attempted to gain access to chromite and rare earth deposits in southern Madagascar. These ventures are still in exploration stages.

- Sudan

- There is speculation Wagner has scouted for uranium and tantalum, though operations remain opaque.

- Zimbabwe (interest, not confirmed control)

- Reports suggest Russian interest in lithium and platinum in collaboration with Chinese firms, but Wagner’s direct involvement is unclear.

Bauxite and Iron Ore (Emerging Interests)

- Guinea

- Russian firms (e.g., Rusal) have long been involved in bauxite extraction. Wagner is reportedly exploring security-for-minerals contracts in remote mining zones.

- Cameroon

- Wagner-affiliated actors have approached local warlords and political elites for access to iron ore fields, especially in contested areas near the CAR border.

Oil (Limited, Strategic Interest)

- Libya

- Wagner protects oil infrastructure in Libya’s south and has tried to influence control over terminals in Sirte and the Fezzan region.

- South Sudan and Chad

- Intelligence suggests Wagner is negotiating access rights to oil blocks in exchange for security contracts, but no confirmed extraction yet.

Summary Table:

| Resource | Countries | Companies / Fronts Involved |

| Gold | CAR, Sudan, Mali | Midas Ressources, Meroe Gold, Lobaye Invest |

| Diamonds | CAR, (possible DRC, Guinea) | Wagner proxies and local armed networks |

| Timber | CAR | Wagner-controlled logging firms |

| Rare Earths | Madagascar, Sudan | Russian-backed exploration teams |

| Bauxite | Guinea | Rusal (state-linked), Wagner interest growing |

| Iron Ore | Cameroon | Negotiated through tribal militias |

| Oil | Libya, Chad, South Sudan | Wagner protects & influences concessions |

Why This Matters

- These operations serve both economic and geopolitical purposes: to fund Wagner’s global footprint, reward elites in host states, and establish leverage in resource-rich zones traditionally dominated by the West or China.

- The opacity and violence surrounding these operations raise legal, ethical, and diplomatic risks for both Moscow and African partners.

- Growing resentment on the ground may eventually trigger local resistance, international sanctions, or anti-Russian insurgencies.

Let me know if you’d like maps, company structures, or financial flows next.

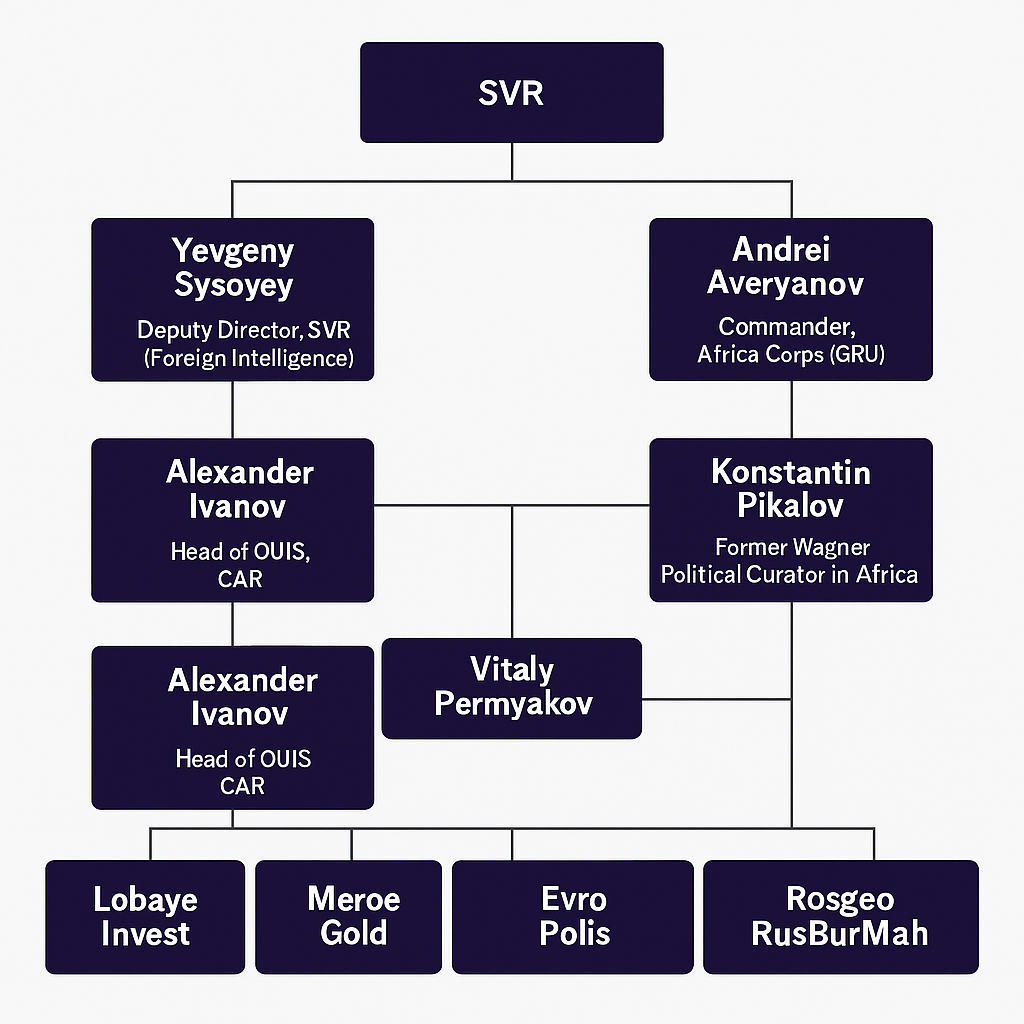

Corporate Structure & Ownership Overview

Midas Ressources SARLU (CAR)

- Founded: Nov 12, 2019 in Bangui

- Role: Operates Ndassima—the only industrial-scale gold mine in CAR, de facto after seizing control from Axmin Inc. post-2017

- Key Individual: Dmitri Sytyi—Wagner operative sanctioned by US/EU; controls Lobaye Invest and related firms

Diamville SAU (CAR)

- Type: Diamond and gold trading shell company

- Registered Owner: Bienvenu Patrick Setem Bonguende (front for Dmitri Sytyi)

- Activity: Purchases and exports diamonds from CAR (e.g., to Belgium, UAE); sanctioned by US/EU in mid-2023 for illicit trade

Lobaye Invest SARL (CAR)

- Linked to Dmitri Sytyi; active in diamond/gold extraction and forestry/logging in Lobaye region

Other Key Entities

- Meroe Gold / M‑Invest (Sudan): Wagner-linked gold processing front; partnered with Sudanese intelligence to access mining zones

- Industrial Resources General Trading (Dubai): Conducted cash-transfer gold schemes with Diamville to repatriate proceeds to Russia

- OOO DM (Russia): Facilitated gold-selling operations for Wagner linked entities

💰 Financial Flows & Exploitation Processes

- Gold Revenue Streams: Estimated $290M/year from Ndassima alone; site valued at around $2.8B total

- Sanctions Evasion: Companies like Diamville converted CAR gold into U.S. dollars via cash smuggling; used Dubai-based intermediaries (Industrial Resources) to evade banking restrictions

- Diamond Exports: Diamville shipped illicit diamonds to Europe and UAE; in 2019 exported €132,000 worth to Belgium; overall up to $12M in exports by 2021

- Logistics routes: Resources smuggled via land routes through Cameroon (Douala port) or Sudan, sometimes by air via private jets to bypass customs

- Banking networks: Despite sanctions, payments were processed via major banks like JPMorgan and HSBC in earlier years, often

Ownership & Control Structure (Simplified)

pgsql

CopyEdit

Russian PMC Wagner Group / Prigozhin network

|

————————————————

| | |

Midas Ressources Diamville SAU Lobaye Invest

(Gold extraction) (Diamond/gold trade) (Timber, logging)

| | |

Controlled by Registered owner Headed by Dmitri Sytyi

Dmitri Sytyi & network (front) B. Setem Bonguende

Funds from these entities were funneled via Industrial Resources (Dubai), OOO DM (Russia), and M-Finance to support operational and logistical costs across Africa.

Summary

- Wagner operates a network of shell companies in CAR and Sudan to extract gold, diamonds, and logs.

- Key figures include Dmitri Sytyi and associates who manage both mining and trading firms.

- Financial flows circumvent sanctions through cash smuggling routes and informal banking networks.

- These operations are legal facades masking illicit looting, making Russia financially independent of formal state budgets in Africa.

Russian mercenaries—primarily from the Wagner Group and its successor Africa Corps—have repeatedly killed local civilians around mining sites in Africa, including the Central African Republic (CAR) and Sudan, for the following key reasons:

⚔️ 1. To Secure and Control Resource Zones

Wagner treats mineral-rich areas (like gold and diamond mines) as militarized zones, and any local presence—whether real or perceived—is treated as a threat.

- Locals are often seen as potential:

- Informants to foreign intelligence or the government

- Competitors in artisanal (informal) mining

- Obstacles to expanding infrastructure or enforcing “exclusive zones”

➡ Example: At the Ndassima gold mine in CAR, Wagner mercenaries reportedly killed dozens of villagers in 2022 and 2023, accusing them of illegal mining—even though many were simply returning to ancestral lands.

💰 2. To Eliminate Witnesses to Exploitation or War Crimes

Many of these killings aim to silence witnesses of Wagner’s:

- Illegal arms-for-resources deals

- Torture and executions

- Use of forced labor

- Destruction of villages for mine expansion

➡ In Zimbabwe’s Marange diamond fields, Russian-linked operatives (and earlier Chinese ones) were involved in similar lethal crackdowns on artisanal miners and locals, mirroring Wagner’s tactics in CAR.

🔒 3. To Maintain Operational Secrecy

Wagner’s mining projects are often tied to sanctions evasion schemes, cash smuggling, and off-the-books funding for Russia’s war in Ukraine.

- Locals in the vicinity could accidentally or intentionally expose:

- Location of mining camps

- Movements of armed convoys

- Secret runways or smuggling routes

➡ Cover-up killings are not uncommon: journalists, human rights workers, and villagers have been killed to ensure silence.

⚠️ 4. To Terrorize and Deter Resistance

The killings serve as psychological warfare: instilling fear to prevent uprisings, leaks, or community resistance.

- In regions with weak or complicit governments, Wagner acts with total impunity

- Massacres and public executions are sometimes used to send a message: “This mine is Russia’s”

➡ Probability of anti-Russian riots remains low in heavily militarized zones due to fear. However, unrest may rise in areas like Ouaka and Mbomou prefectures in CAR, where local resentment is growing.

More on this story: Africa’s New Overseers: Inside Russia’s Covert Gold Empire”

Posted inWar crimes Warfare

More on this story: Attack on Chimbolo mine in view of Xi’s Moscow visit

🧩 Summary Table

| Motivation | Explanation | Example |

| Resource Control | Locals seen as competition or trespassers | Ndassima mine killings |

| Witness Elimination | Locals could expose looting, war crimes | Massacres after village sweeps |

| Secrecy | To hide operations tied to sanctions evasion | Killings near airstrips/logistics hubs |

| Fear & Deterrence | Prevent resistance and uprising | Executions of “suspicious” villagers |