Recent developments in Moldova indicate a significant realignment within the country’s pro-Russian political spectrum. Formerly fragmented forces have now coalesced into a unified electoral bloc, potentially reshaping the political landscape ahead of the 2025 general elections. This consolidation could challenge the pro-European trajectory of the current administration and poses risks for Moldova’s democratic stability.

II. Strategic Realignment: Who Are the Players? Key actors in this alliance include the Revival Party (Partidul Renaștere), the Șor movement, and satellite groups in Gagauzia and Transnistria. Coordinated messaging, shared financial resources, and Russian media support suggest a centrally directed effort, likely backed by Moscow. The unification reflects a tactical move to overcome the electoral threshold and pool influence across rural and Russian-speaking regions.

III. Why Now? Timing and Context The timing is no coincidence. With Maia Sandu’s government seeking deeper integration with the EU and maintaining strong ties with Ukraine, Moscow views the upcoming elections as a last window of opportunity to reverse Moldova’s westward path. The energy crisis, inflation, and disinformation campaigns have created fertile ground for populist narratives. Russian intelligence operations are increasingly active, shaping political opinion through economic pressure and cultural propaganda.

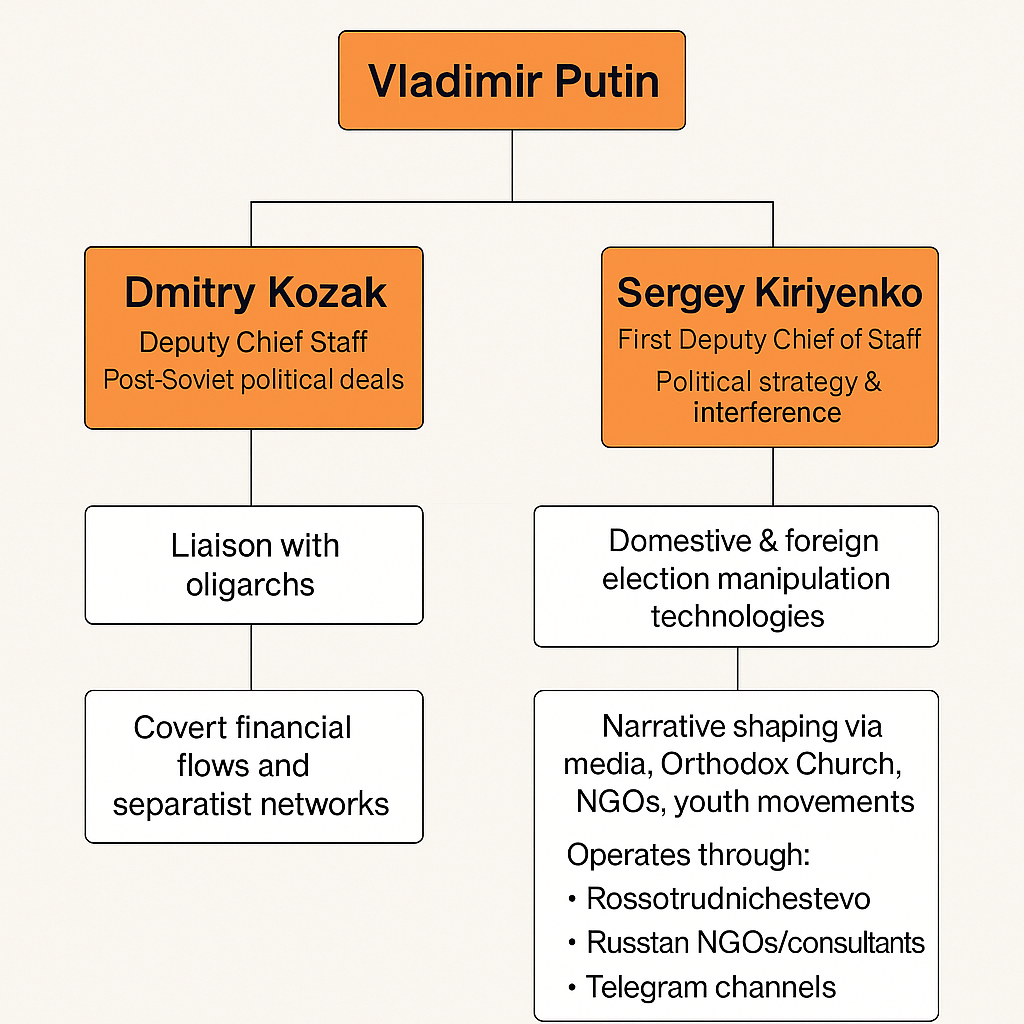

While the coordination appears locally driven, two high-level Kremlin figures are believed to play pivotal roles. Dmitry Kozak, a veteran of Moscow’s Moldovan policy since the early 2000s, maintains backchannel ties with oligarchic and separatist actors in Gagauzia and Transnistria. However, Sergey Kiriyenko, the Kremlin’s “political technologist-in-chief,” now reportedly manages Russia’s electoral manipulation campaign. Kiriyenko’s team orchestrates digital propaganda, party engineering, and pro-Russian content pipelines, making him the de facto manager of the Kremlin’s hybrid campaign in Moldova.

. Electoral Chances and Regional Strongholds Polls suggest the pro-Russian bloc could secure between 20–30% of the vote if elections were held today, especially in Gagauzia, the south, and Russian-majority urban centers like Bălți. Their success depends on turnout, opposition coordination, and the ability to mobilize diaspora votes. Fragmentation among pro-European forces could play directly into their hands.

V. Risks for Democratic Forces The united front of pro-Russian actors raises the stakes for democratic forces:

- Electoral Disinformation: Russia-backed media may intensify smear campaigns targeting Sandu and PAS.

- Vote-Buying and Black Cash: The alliance could exploit covert Russian funding to sway economically vulnerable voters.

- Legal Manipulation: Attempts to discredit or legally challenge electoral procedures are probable.

- Hybrid Tactics: Use of Orthodox Church networks, social unrest, and cyber-operations to demoralize pro-EU voters.

VI. Probable Tactics of the Pro-Russian Bloc

- Economic Populism: Promising subsidies, pensions, and Russian gas discounts.

- Cultural Identity Politics: Framing EU integration as anti-Orthodox, anti-family, or ‘foreign occupation.’

- Diaspora Manipulation: Targeting Moldovans abroad via churches, media channels, and organized transport.

- Election-Day Obstruction: Coordinated protests or provocations to delay or delegitimize results.

VII. Recommendations to Counter Influence

- Strengthen Electoral Commission Oversight: Ensure transparency in campaign financing and ballot monitoring.

- Information Campaigns: Preempt disinformation with local-language factual outreach, especially in rural areas.

- Judicial Preparedness: Fast-track court readiness for potential electoral disputes or vote fraud.

- Regional Outreach: Increase state presence in Gagauzia and Bălți to counter separatist narratives.

- Diaspora Mobilization: Enable and secure diaspora participation through embassies and digital outreach.

The unification of Moldova’s pro-Russian political forces marks a critical inflection point. With high stakes for the country’s geopolitical future, the next elections are not merely domestic—they are a front in a broader struggle between European integration and Russian revanchism. Democratic forces must act with urgency, coordination, and resilience to defend Moldova’s sovereignty and democratic path.

The unofficial manager of the Russian campaign in Moldova from the Kremlin is widely believed to be Dmitry Kozak, former Deputy Head of the Russian Presidential Administration and a longtime strategist for Moscow’s operations in post-Soviet states. While he has no formal portfolio in Moldova today, his longstanding relationships with local elites and Russian-aligned networks keep him influential behind the scenes.

- Trusted by Putin for “Gray Zone” Operations: Kozak has long been entrusted with politically sensitive dossiers where deniability is crucial—Transnistria, Donbas negotiations, and managing oligarchs. Moldova fits that pattern perfectly, particularly given Moscow’s need for a low-visibility but high-impact strategy in the 2025 elections.

- Liaison to Local Operatives: Kozak is believed to maintain informal ties with Moldovan oligarchs such as Ilan Shor (now in exile) and figures in the Revival and Șor blocs. Reports from Moldovan intelligence and leaked Kremlin coordination memos (e.g., “Moldova 2030” plans) place Kozak’s staff in the loop of operational planning, including media, electoral logistics, and diaspora manipulation.

- Coordination with Russian Security Services: Though Kozak is a civilian political operative, he often works closely with the FSB and SVR to align political manipulation efforts with covert operations, especially in influence zones like Moldova, where both intelligence penetration and soft power are combined.

Who Really Manages Russia’s Moldova Campaign—Kozak or Kiriyenko?

1. Dmitry Kozak – The “Old Guard” Operative

- Role: Traditional overseer of post-Soviet policy toward Moldova and Transnistria.

- Method: Negotiator, oligarch handler, and liaison to local elites.

- Focus: Subtle political engineering, energy leverage, and economic deals.

- Relevance: Still holds informal ties with Moldovan networks but appears less visible since 2022.

2. Sergey Kiriyenko – The Current Kremlin Architect of Political Technologies

- Role: First Deputy Chief of the Presidential Administration; key figure in “managed democracy” operations both inside Russia and abroad.

- Method: Strategic use of technocrats, media manipulation, youth programs, and Kremlin NGOs.

- Focus: Orchestrating election interference, propaganda content, and building loyal ideological parties or influencers.

- Relevance: Kiriyenko is now widely seen as the central figure behind the export of “sovereign democracy” to fragile neighboring states, including Moldova.

How It Likely Works in Moldova: Dual Structure

- Kiriyenko oversees political technology, election interference, and strategic narrative control—via entities like Rossotrudnichestvo, pro-Russian influencers, Telegram channels, and Gagauzia-based info hubs.

- Kozak still manages contacts with oligarchs (like Ilan Shor), Gagauz leaders, and Transnistrian elites—and is more involved in quiet political brokering, financial channels, and guarantees to Russia-linked Moldovan actors.

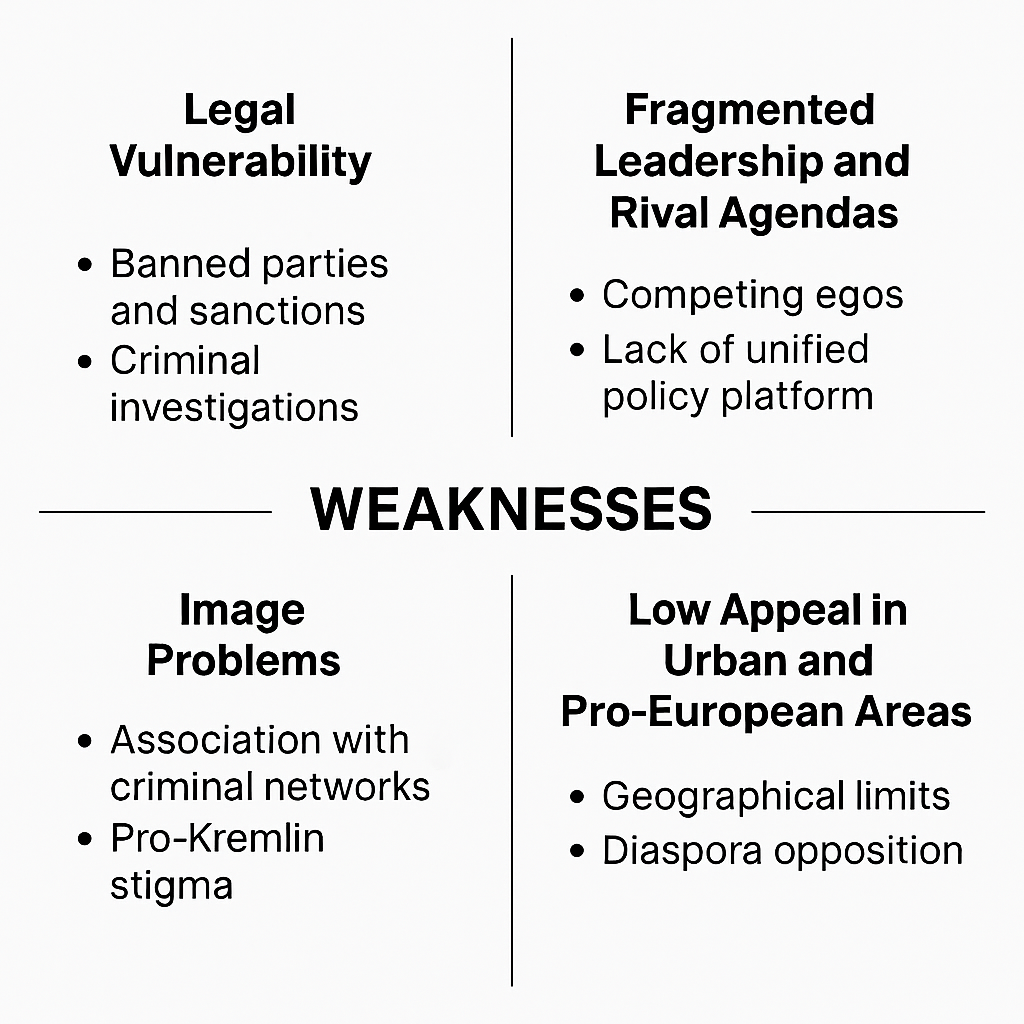

- 1. Legal Vulnerability

Banned Parties and Sanctions: Key components like the Șor Party have been outlawed, and several leaders face international sanctions. Any attempt to recycle banned entities into new political labels risks disqualification by Moldova’s Constitutional Court.

Criminal Investigations: Many figures involved have ongoing investigations for corruption, fraud, or illegal funding. This creates pressure points for legal or electoral exclusion.

2. Fragmented Leadership and Rival Agendas

Competing Egos: Despite temporary unity, power struggles between figures like Ilan Șor, Evghenia Guțul, and regional leaders in Gagauzia and Transnistria could resurface.

Lack of Unified Policy Platform: The bloc largely operates on anti-Sandu rhetoric rather than a coherent alternative program, making it fragile under scrutiny or during televised debates.

3. Low Appeal in Urban and Pro-European Areas

Geographical Limits: Their appeal is concentrated in the south (Gagauzia), Bălți, and Transnistria. Major cities like Chișinău, Ungheni, and the northern regions lean pro-European.

Diaspora Opposition: The Moldovan diaspora—especially in the EU—is overwhelmingly pro-Western and may counterbalance rural support if turnout is high.

4. Image Problems

Association with Criminal Networks: Ties to fugitive oligarchs and black cash undermine credibility among undecided voters.

Pro-Kremlin Stigma: As the war in Ukraine continues, associating too closely with Russia may alienate moderates who fear instability or economic isolation.

5. Overreliance on External Support

Moscow’s Micromanagement: The bloc’s coordination often depends on Kremlin operatives like Sergei Kirienko or the Presidential Directorate for Interregional Relations, limiting flexibility.

Funding Vulnerability: Sanctions and international financial scrutiny reduce the bloc’s access to black funds and money laundering routes.

6. Weak Policy Depth

Lack of Economic Vision: Their populist promises (cheap gas, pensions, subsidies) are often unbacked by viable policy, especially given Moldova’s limited fiscal space.

EU Skepticism in an EU Candidate State: As Moldova begins formal EU accession talks, anti-European rhetoric can appear regressive or disconnected from voter aspirations.