Since July 13, the Sweida province in Syria — an area with about 500,000 inhabitants, mostly of Druze faith — has been engulfed in fierce conflicts between local Druze militias, Bedouin tribes, and the new government forces that took power after the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December last year.

At the height of the violence escalation, on July 16, Israel intervened militarily by bombing the Ministry of Defense in Damascus. Israeli authorities stated that the action aimed to protect the Druze community in Syria.

The subsequent ceasefire agreement — mediated by the US and Turkey — calls for the withdrawal of government forces from Sweida and the integration of the region into the new government’s state structures.

However, the situation remains unstable, although on the surface, the parties appear to be respecting the agreement.

Who are the Druze?

The Druze are a monotheistic religious community that emerged in the 11th century as a branch of Ismailism, a sect of Shia Islam, but with unique esoteric doctrines that distinguish them both from Islam and other Abrahamic faiths.

The name “Druze” derives from an early preacher, Muhammad bin Ismail ad-Darazi, who was declared a heretic and later executed.

Over centuries, they have tried to remain neutral in regional conflicts, focusing on protecting their community.

The Druze do not identify as Muslims and maintain a closed faith, strictly inherited and preserved. They honor prophets such as Jesus, Muhammad, and Moses but reject proselytism and practice a belief system combining religious, philosophical, and gnostic elements.

Ethnically, the community is Arab but culturally very cohesive, with a strong emphasis on loyalty and internal autonomy.

Today, the Druze population is estimated between 800,000 and 1 million, mostly in Syria and Lebanon, about 10% in Israel, and a small number in Jordan and diaspora.

The Druze in Israel

About 150,000 Druze live in Israel, mainly in the north—in Mount Carmel, Galilee, and the Golan Heights. They speak Arabic and are an integral part of Israeli society.

Since the establishment of Israel, Druze men have been conscripted into military service, often achieving important ranks in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

However, the situation differs for the 22,000 Druze living in the Golan Heights, Syrian territory annexed by Israel after the 1967 war. The relationship between the Israeli State and them is more complex. Over the years, the Druze have refused Israeli citizenship, maintaining ties with Syria. But since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, these ties weakened, and interest in Israeli citizenship increased.

Druze in Syria: A Community at Risk

Since the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad in December 2024 by rebel groups, ethnic and religious minorities in Syria—including the Druze—have faced a sharp increase in insecurity.

The new Syrian president, Ahmad al-Sharaa, with previous ties to al-Qaida, has promised to protect minority rights. Yet sectarian killings and ongoing tensions have been reported. The massacre in the Alawite community should not be forgotten.

Meanwhile, the Druze have formed self-defense forces to protect themselves from extremists who consider them heretics.

In 2018, ISIS attacked the Sweida region, killing over 200 people and abducting dozens. In April this year, a suspicious audio recording circulated, allegedly of a Druze leader insulting Prophet Muhammad, although the sheikh denied it. This incident sparked a wave of violent clashes in Sweida.

In May, a ceasefire agreement was signed between the government and local Druze leaders, but some factions refused to disarm, blaming each other for the insecurity.

This division among communities and countries makes the Druze vulnerable to regional conflicts. Their unique military alliance with Israel, which distinguishes them from other Arab minorities, seems to give Israeli authorities a reason to intervene when the Druze feel threatened.

At the same time, being spread across States often plagued by interfaith tensions, pressure on one part of the community causes immediate reactions in other parts, turning local crises into international issues.

In Syria, the community is currently divided: some religious leaders have joined the national unity project promoted by Damascus, seeking a role in the new political scene. Others fear discrimination and oppression by a government perceived as linked to radical Islamism.

Today, the Druze are targeted because they represent a religious and cultural minority considered “heterodox” and suspicious by the new Sunni authorities after Assad’s fall.

Recent Escalation

Violence escalated on July 11, when a young Druze was attacked by armed Bedouins on a road supposed to be under Syrian army control.

In retaliation, Druze militants captured several Bedouins, leading to new sectarian clashes. When the army intervened, the Druze accused it of collaborating with the aggressors.

Brutal videos surfaced online: in one, government militiamen insult Druze religious leaders and pull sheikhs’ mustaches—a serious religious insult. Other videos showed Druze fighters beating and executing captured government forces.

Protests spread to Israel, where hundreds of Israeli Druze crossed the border to aid their community in Syria.

Israel increased military intervention, striking Syrian tanks near Sweida and then strategic targets in Damascus and Latakia.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) also evacuated and medically treated several Druze from Syria and distributed humanitarian aid in Sweida.

In this climate of insecurity, the entry of around 1,000 Israeli Druze into Syria to assist their co-religionists gave Israel an opportunity for military intervention.

Israel, for its part, has strengthened ties with Druze tribal leaders and community authorities, mainly to ensure these areas are not infiltrated by jihadist groups.

Netanyahu’s recent statement that he “will not tolerate Islamist gangs at the border” should be understood not only as a threat to the new Syrian government but also as a protective message to the Druze: a way to prevent sectarian attacks and, simultaneously, consolidate a tactical alliance with a minority that has always been pragmatic, though officially distant from Zionism.

This cooperation follows previous models: local self-defense, intelligence exchange, but without formal or ideological adherence.

There are clear signs that some parts of the Syrian Druze community discreetly but importantly cooperate with Israel. Especially in border areas like the Golan Heights and the Sweida region, local Druze have facilitated Israeli intelligence operations and are believed to have provided information on Islamist militias linked to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) or other radical Sunni groups that gained influence in the power vacuum after Assad’s regime collapse.

Possible Normalization?

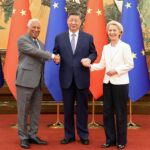

After Assad’s overthrow, Israel occupied an 80-kilometer border zone in Syria, destroying Syrian military assets to prevent their falling into the hands of radical militias. However, in recent months signs of possible dialogue between Israel and Syria, mediated by the US and Turkey, have emerged.

In May, diplomatic sources reported that senior officials from both countries met in Baku. But after the recent outbreak of violence, many in Israel doubt the sincerity of al-Sharaa’s government.

In today’s Syria, the question “who protects whom?” is essential to understanding the country’s unstable power balance.

Russia, Iran, Turkey, the United States and Israel remain guarantors of various communities by region.

Thus, Syria today is divided into a network of de facto protectorates, where every minority group or armed faction relies on an external protector to ensure its survival and zone of control.