In mid-2025, the United States expanded its sanctions regime to target the so-called “shadow fleet” — an extensive network of vessels operated covertly to circumvent oil and gas embargoes imposed on Russia and Iran. This move marks a significant escalation in Washington’s effort to curb illicit hydrocarbon exports that have become a critical lifeline for both sanctioned regimes. The new measures strike at the maritime core of the Kremlin-Tehran partnership, signaling a deepening concern over the economic and geopolitical impact of the shadow fleet’s operations.

II. The Role of the Shadow Fleet in Russia’s Sanctions Evasion Strategy

Following the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Western sanctions dramatically reduced Russia’s access to global markets. In response, Moscow began using unregistered or falsely flagged tankers, often with opaque ownership structures, to export oil to countries like China, India, and Turkey. This shadow fleet became essential to Russia’s ability to sustain wartime revenues — especially after the G7-imposed price cap on Russian oil.

Key purposes:

- Evading price caps and shipping insurance restrictions

- Concealing origins and destinations of crude

- Avoiding automatic sanctions enforcement mechanisms

Iran’s decades of sanctions-evasion experience offered Russia both operational expertise and physical infrastructure — including oil transfer hubs and port access — especially in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea.

There have been multiple historical cases of using clandestine or “shadow” fleets to evade international sanctions. While the modern scale and sophistication of the Russia-Iran operation is unprecedented, earlier analogues demonstrate similar tactics. Below are key examples:

1. Iran (1980s–present)

Context: U.S. sanctions after the 1979 Islamic Revolution and later over the nuclear program.

Tactics Used:

- Changing vessel flags frequently (flag-hopping).

- “Ghost ships” turning off AIS (Automatic Identification System).

- Use of front companies in Malaysia, the UAE, and China.

- Ship-to-ship transfers near Singapore, Oman, and in the Strait of Hormuz.

Impact: Iran managed to export oil covertly, especially to China and India, often through intermediaries and oil labeled from other countries.

2. Iraq (1990s – Saddam Hussein Era)

Context: UN sanctions after the 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

Tactics Used:

- Illicit oil smuggling through Jordan, Syria, and Turkey.

- Use of small barges and unregistered tankers in the Persian Gulf.

- Bribes and fake documentation in neighboring states.

Impact: Saddam’s regime earned billions in illicit revenues via the Oil-for-Food Programme abuse and black-market sales.

3. North Korea (2006–present)

Context: Sanctions over nuclear and missile programs.

Tactics Used:

- Renaming and repainting ships.

- Illegal ship-to-ship transfers in international waters.

- Using Chinese ports and shell companies for cover.

- Engaging foreign-flagged vessels (mainly from Panama, Belize, and Cambodia).

Impact: Pyongyang has imported refined fuels and exported coal despite a near-total UN embargo.

4. Venezuela (2017–present)

Context: U.S. and EU sanctions over human rights abuses and disputed elections.

Tactics Used:

- Coordinated with Iran to swap oil for fuel and other goods.

- Use of “dark fleet” tankers with turned-off transponders.

- Operations run via Russian and Chinese front companies.

Impact: Despite sanctions, Caracas continued limited oil exports to China and other nations using opaque methods.

5. Apartheid South Africa (1970s–80s)

Context: UN sanctions due to apartheid policies.

Tactics Used:

- Covert oil imports via front companies.

- Collusion with Iran, Israel, and oil traders.

- Routing through Portugal, the Netherlands, and Liberia.

Impact: Helped sustain South Africa’s economy despite an oil embargo.

Takeaways Compared to Russia-Iran 2020s Operation:

| Feature | Historical Cases | Russia-Iran Shadow Fleet |

| Flag hopping | Common | Extensive and systematic |

| AIS spoofing | Rarely used | Routinely used |

| Ship-to-ship transfers | Used in some cases | Core method |

| Volume | Limited by scale | >1.5 million barrels/day combined |

| Financial support | State-level or private | State-directed with intelligence backing |

| Sanction evasion hubs | Limited | Global (UAE, Singapore, Turkey, China) |

III. Why Russia Uses Iranian Vessels and Infrastructure

Russia’s growing dependence on Iranian shipping assets stems from:

- Preexisting Expertise: Iran has long operated illicit maritime logistics under U.S. sanctions. Its networks, forged through the IRGC, provided Russia with a ready-made template.

- Ship Registries and Flags of Convenience: Many Iranian-controlled vessels operate under third-party flags — including Panama, Belize, and the Marshall Islands — offering plausible deniability.

- Insurance Laundering: Tehran developed shell companies in Asia and the Middle East to insure tankers outside of Western-dominated maritime insurance systems.

- Geopolitical Solidarity: The Iran-Russia axis sees maritime collaboration as a way to counterbalance Western maritime dominance, particularly via NATO and EU navies.

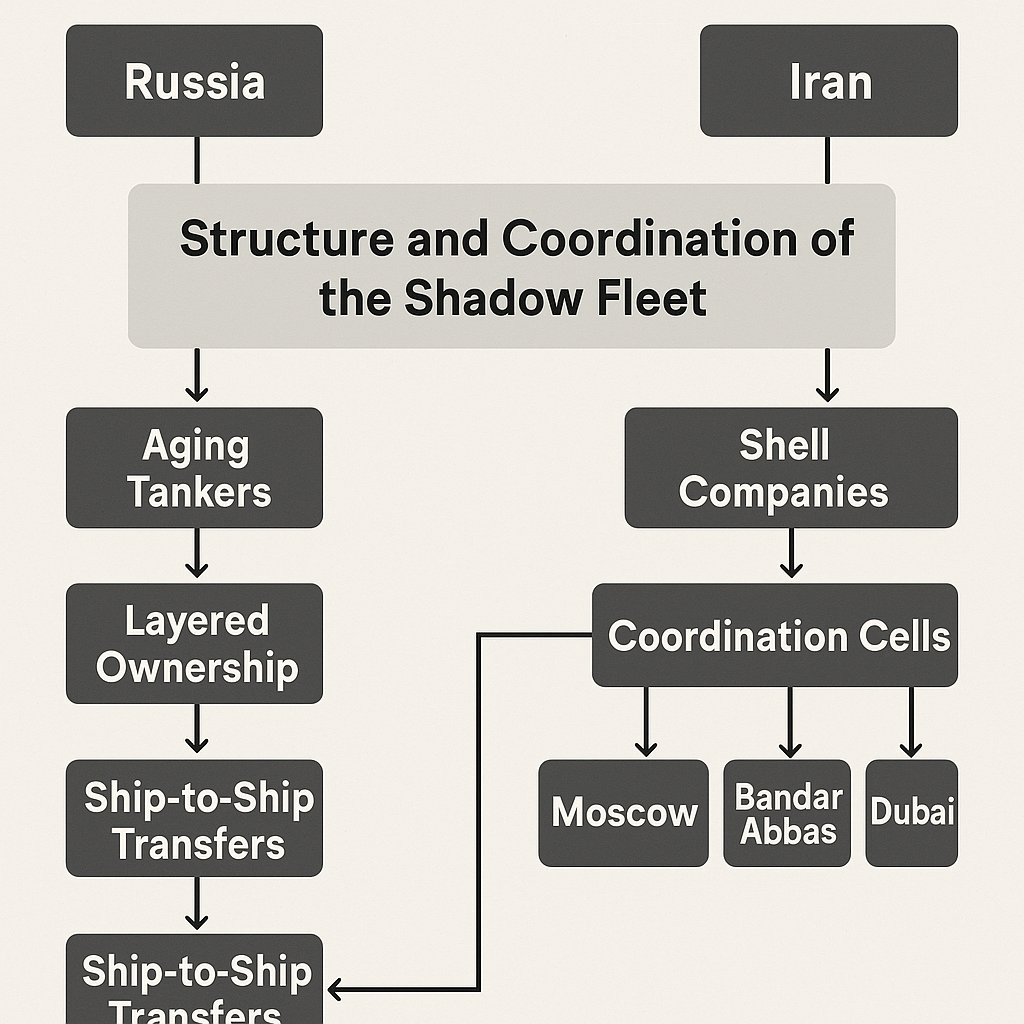

IV. Structure and Coordination of the Shadow Fleet

The fleet is a complex, decentralized, and opaque system. It includes:

- Aging tankers bought cheaply and operated with falsified documentation

- Layered ownership via offshore shell companies, often in the UAE, Hong Kong, and Cyprus

- AIS (Automatic Identification System) manipulation to spoof vessel locations

- Ship-to-ship (STS) transfers in international waters (notably off Greece, UAE, and Sri Lanka)

- Coordination cells operating out of Moscow, Bandar Abbas, and Dubai, involving former intelligence operatives and logistics experts

A Russian-Iranian “tanker swap” system has emerged: Iranian tankers deliver oil to Russia’s Far East or Black Sea ports in exchange for Russian shipments to Asia — a means to blur provenance and optimize shipping routes.

V. What Is Needed to Eliminate the Shadow Fleet

To dismantle this fleet, several measures are essential:

- Global Maritime Enforcement Coordination

A NATO–G7 task force capable of tracking shadow fleet movements, targeting STS locations, and freezing flagged vessels in compliant ports. - Maritime Insurance and Finance Cracking Down

Tighter regulation and audits of marine insurers and banks in Asia and the Gulf — particularly Dubai, Singapore, and Malaysia — that indirectly support these networks. - AIS and Satellite Monitoring

Enhanced global tracking using real-time satellite surveillance, including thermal imaging and ship wake detection. - Secondary Sanctions

Hitting companies in China, India, or the Gulf that purchase shadow fleet oil with full asset freezes and access denial to the U.S. market.

VI. Why It’s Difficult to Dismantle

Despite robust legal tools, eliminating the shadow fleet faces major challenges:

- Legal Grey Zones: Many operations take place in international waters, making enforcement complex.

- Maritime Sovereignty: Countries hosting flags of convenience are reluctant to act decisively.

- Asian Resistance: China and India, key buyers of shadow fleet oil, reject extraterritorial U.S. sanctions.

- Fleet Size and Mobility: Hundreds of vessels operate with flexibility and deniability, making complete interdiction near impossible.

VII. Economic Impact of Shadow Fleet Activities

The economic role of the shadow fleet is vital for both regimes:

- Russia: Roughly 30–40% of Russia’s oil exports (up to 2 million bpd) now move via shadow methods, generating $60–70 billion in annual revenue despite sanctions.

- Iran: Proceeds from clandestine oil sales fund not only domestic needs but regional proxies like Hezbollah and Houthis.

The shadow fleet undercuts global sanctions architecture and allows the Kremlin to finance its war in Ukraine and Iran to sustain its regional interventions.

Conclusion

The U.S. crackdown on the shadow fleet is a long-overdue attempt to seal critical revenue leaks in the sanctions regime. But the resilience and adaptability of the Russia-Iran maritime alliance present major obstacles. Unless there is broader international coordination — especially involving key oil importers — efforts to disable the fleet may remain symbolic. The shadow fleet is more than just a logistics network; it is a maritime expression of multipolar resistance to Western sanctions dominance.