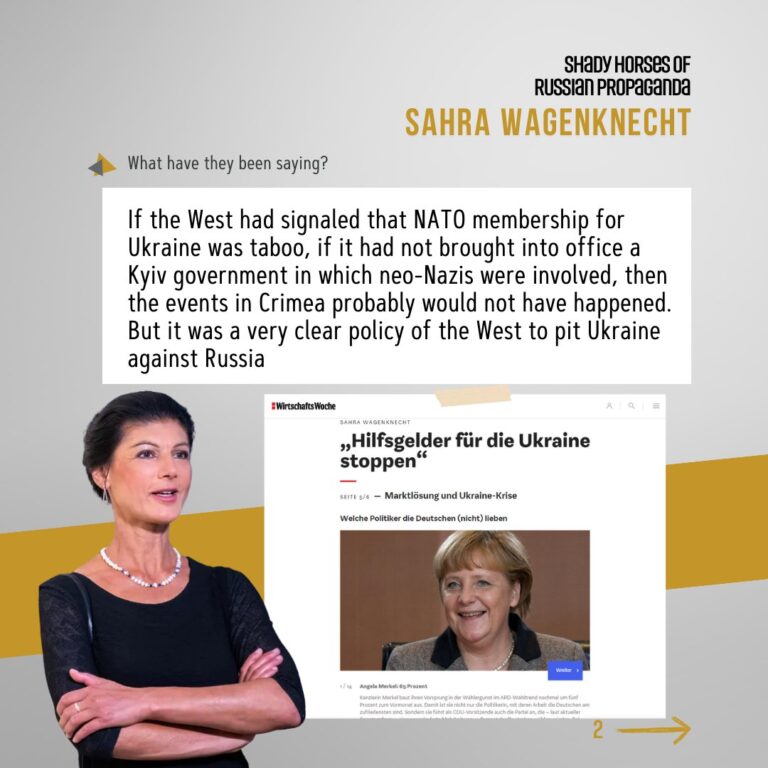

As we previously noted, the pro-Russian orientation of the German party Alliance Sahra Wagenknecht has begun to reveal itself — particularly through its facilitation of Kremlin propaganda in Germany and its provision of a public platform to a Russian diplomat for that purpose, in open defiance of the positions of the German government and Foreign Ministry.

More on this story: Kremlin Maneuvers Stasi Agents into Power in Germany

More on this story: Kremlin to use Germany for EU breakup

On the Russian dictator’s birthday, October 7, 2025, Russia’s ambassador to Germany, Sergei Nechayev, attended the opening of an art exhibition at the Landtag of Brandenburg, invited by the left-populist Alliance Sahra Wagenknechtparty. Until now, there had been an unofficial taboo among German political forces on inviting or allowing Russian diplomats to participate in public political events.

The party organized the exhibition, titled “War and Peace” (Krieg und Frieden), in the Landtag building in Potsdam, featuring works by Hans and Lea Grundig, artists from the former East Germany and members of the Communist Party. Representatives of several embassies and pacifist organizations were invited. The first to confirm participation were representatives from Russia, Belarus, and Hungary.

During the opening, the spotlight fell not on the paintings but on the invited Russian ambassador, Sergei Nechayev. Members of the Christian Democratic Union (the party of Chancellor Friedrich Merz) expressed outrage over the invitation of an envoy from an aggressor state to an event titled “War and Peace.” Jan Redmann, head of the CDU faction in Brandenburg, urged people to “stay away from this event, because anyone who attends becomes a silent accomplice to Russian war propaganda.”

“Russia is responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people as a result of its brutal invasion,” he said, reminding that “women were raped, children abducted, hospitals bombed.” He added: “Russia’s war knows no humanity. Anyone giving a platform to Russian war criminals has nothing to do with peace.”

Redmann concluded that, for the Alliance Sahra Wagenknecht, the word peace really means Russia’s victory. Similar criticism came from Clemens Rostock, head of the Green faction in the Landtag, and Björn Lüttmann, head of the SPDfaction. Germany’s Foreign Ministry also issued guidance urging the avoidance of Russian diplomatic participation in official events.

European governments, diplomatic institutions, and political parties should avoid involving Russian diplomats in public official events after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Normalizing aggression is unacceptable; participation by Russian diplomats can be seen as legitimizing the Kremlin’s actions.

Key considerations include:

• Refusing participation of Russian diplomats is a clear act of condemning Moscow’s aggressive war against Kyiv.

• Reducing Russian diplomatic presence in European public life directly diminishes the impact of Russian propaganda. Russian envoys actively exploit public platforms to spread anti-democratic, anti-liberal, and neo-imperial narrativesthat contradict European values.

• Limiting Russian influence in European domestic politics strengthens the protection of democratic processes. This has been demonstrated in recent elections in Romania and Moldova, where Russian diplomats interfered in campaigns and sought to destabilize internal politics.

• Technical-level dialogue with Russian officials continues through “closed” communication channels — necessary for handling urgent issues — but does not imply political normalization.

• Engagement with Russian representatives remains a sensitive matter balancing diplomacy, morality, and strategic interest. EU diplomats may interact with Russian counterparts within international organizations where Russia remains a member (such as the UN), using such occasions to subject the Putin regime and its aggression to thorough and public criticism.

Key ways Russia can use BSW for the next goals:

- Legitimization / normalization of Kremlin narratives — By appearing alongside respected local politicians and at civic events, Russian diplomats and media can make pro-Kremlin frames (e.g., “peace”, anti-Western criticism, grievances about NATO) look mainstream rather than fringe. This effect intensifies if BSW organizes or hosts events where Russian envoys attend.

- Amplification of propaganda and talking points — BSW’s messaging (left-populist anti-establishment + criticism of sanctions/foreign policy) overlaps with narratives Moscow pushes in Europe; the party can repackage Kremlin themes for a German audience (economic hardship, Western hypocrisy, “peace” framing) and spread them through domestic media and social channels.

- Access to political networks and local institutions — Where BSW gains local office or coalition influence (state parliaments, coalitions), Russian actors can exploit formal and informal access to officials, commissions, cultural programmes, and procurement decisions — strengthening footholds and creating friction in coalition politics.

- Electoral influence and voter mobilization — Moscow can use supportive parties to sharpen political polarization, shift public opinion on Ukraine/sanctions, and indirectly affect election outcomes (through messaging, targeted media, or covert funding/contacts). European investigations have shown Moscow’s willingness to financially reward or support sympathetic actors across Europe.

- Intelligence and information collection — Invitations, official meetings, social events, and coalition negotiations provide opportunities to gather political intelligence, identify useful contacts, and map fault lines inside German politics. Public cultural events are low-risk venues for such engagement

- Policy leverage and vetoing initiatives — A domestic party pushing for “dialogue”, sanctions relief, or different energy policy can be used to complicate or delay unanimous EU/German measures that hurt Russian interests (e.g., sanctions, military aid to Ukraine, energy diversification policies)

Short scenarios (plausible pathways)

- Low-risk normalization: BSW frames attendance of Russian diplomats as cultural/peace diplomacy; German mainstream voices remain critical but the event is used in pro-Kremlin media to claim normal ties, shifting some public sentiment. (Already observable where ambassadors attend cultural events.

- Medium-risk influence campaign: Coordinated messaging across BSW media channels, sympathetic outlets and foreign social media amplify a “peace” narrative that questions military support for Ukraine—reducing domestic support for continued aid and slowing policy responses.

- High-risk penetration: If BSW gains substantive governing posts in states or national influence, Moscow could use that leverage to obstruct sanctions implementation, win procurement contracts, or create political cleavages in Germany’s foreign policy—altering EU cohesion.

Concrete indicators to watch (early warning signs)

- Repeated joint appearances of BSW officials with Russian diplomats beyond one-off cultural events

- Messaging alignment: BSW press releases or social posts echo Kremlin frames (sanctions-harm, NATO-blame, “peace at any cost”).

- Unexplained funding flows, gifts, travel or media buys that benefit BSW actors or sympathetic outlets (investigative leads).

- Increased contact patterns between BSW staffers and known Russian diplomatic or commercial actors (event invitations, working groups).

- Domestic policy proposals from BSW that would materially benefit Russian economic or geopolitical interests (e.g., loosened sanctions, project approvals).

How German government can response:

- Political de-legitimization where appropriate — Public, fact-based pushback by mainstream parties and institutions when Russian envoys are visibly used as political props (clarify why participation is problematic). Example: public statements, parliamentary questions, media responses.

- Transparency rules for events — Require public disclosure of invitations, funding, and guest lists for official/state-level events held in parliamentary buildings or state institutions. This reduces covert normalization.

- Media literacy & counter-narratives — Rapid rebuttal units and reliable explanations showing the human cost of the Kremlin’s war; targeted efforts to inoculate voters against messaging that reframes aggression as merely a “Western problem”.

- Investigate and regulate illicit influence — Strengthen investigation of foreign funding or covert support to domestic actors (apply lessons from EU probes into paid pro-Kremlin influence). Criminalize undisclosed foreign political interference.

- Limit official platforms for diplomats when warranted — Follow guidance (where lawful and proportionate) limiting use of state institutional spaces for foreign diplomats linked to state propaganda campaigns; preserve channels for technical diplomacy but not public legitimization.

- Engage voters on policy substance — Offer concrete, credible alternatives to BSW framing on energy, living standards, and security to reduce the appeal of simple “peace vs. war” binaries Moscow exploits.

Final note (summary)

A party like the BSW can be highly useful to Moscow not (necessarily) because it is a puppet, but because its ideology and public reach overlap with Kremlin narratives. That alignment lets Russia: legitimize its positions, amplify talking points domestically, gather useful contacts, and—at scale—create political friction inside Germany and the EU. Recent events (invitations of Russian diplomats to high-profile cultural/political venues) show how that dynamic can look in practice.