The Russian leadership, represented by Patrushev and Naryshkin, is seeking to accelerate the power transition in the country by exploiting speculation about the health of the Chinese leader.

The Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) of Russia has prepared a report claiming that, despite the efforts of his attending physicians, the health of China’s leader Xi Jinping is deteriorating. The SVR is attempting to convince the Russian political bureau that members of China’s leadership expect Xi to step down from active governance before April of next year.

The report emphasizes that this situation creates nearly ideal conditions for the final stage of Russia’s own power transition, since Beijing, in that scenario, would not interfere with the process in Moscow.

More on this story: Russia’s Managed Succession: Signs of an Approaching Power Transit

We are convinced that the SVR continues to engage in disinformation, supplying the Kremlin with materials based on open sources of dubious credibility.

A similar information operation by the Kremlin came to our attention in June of this year. It was carried out through the same information channels, which indicates that the intended audience is internal—Russian decision-makers themselves. Thus, the goal of this disinformation campaign is to push internal actors toward specific political actions.

One plausible hypothesis is that this disinformation is also intended for Washington, presented as an “insider insight” from China, to extract mutual concessions or benefits from the United States—for example, regarding the supply of Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine.

However, the most credible and probable explanation is the desire of figures close to President Putin to accelerate the process of power transition in Russia.

A similar tactic was employed in 2020–2021, when information about Putin’s own health circulated through the same channels. The repetition of this method, now in relation to China, resembles a latent palace coup.

The Fragile Core: How Concerns About Xi Jinping’s Health Could Shape China’s Political Future

1. Introduction — Leadership Health and Authoritarian Stability

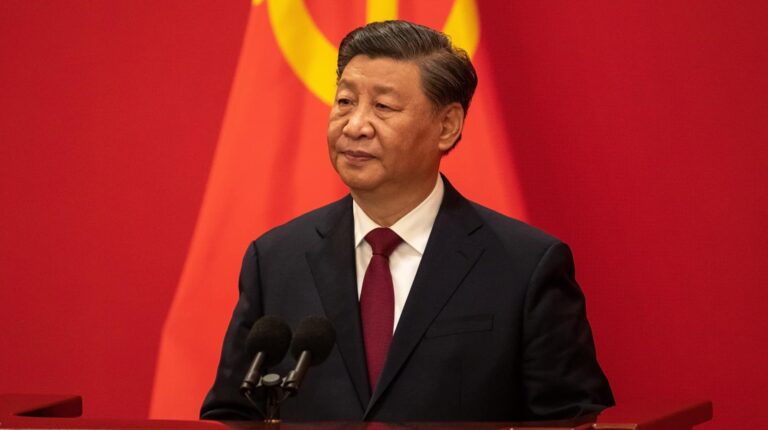

In authoritarian systems built around a single dominant figure, the leader’s physical and cognitive vitality often becomes inseparable from the regime’s stability. China’s President Xi Jinping, who has consolidated more personal power than any Chinese leader since Mao Zedong, now embodies the very structure of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its strategic direction.

Recent speculation in diplomatic circles about Xi’s possible health challenges has revived a critical question: what happens when the cornerstone of China’s modern political system begins to show signs of frailty?

While Beijing has offered no official confirmation of any health concerns, the opaque nature of elite politics, reduced public appearances, and unusual delegation patterns have fueled quiet debate among China-watchers and regional intelligence services. In China’s political context—where the leader’s strength symbolizes national vitality—even rumors of vulnerability can trigger succession anxiety and policy inertia.

What is publicly reported

- Several overseas news outlets report rumours that Xi may have suffered a stroke (or multiple strokes). For example, one article states:

“Unverified reports suggest Xi may have suffered a stroke, sparking speculation about China’s one-man rule.”

Another claims a “third stroke” and hospitalisation.

These remain unverified.

- Fact-checkers have pushed back on some of the more dramatic claims: for example, Reuters found that photos purportedly showing Xi during a stroke were mis-captioned and that as of July 2024 there were no credible reports of a stroke.

- There are “signals” but no proven medical facts: e.g., reduced public appearances, unusual delegation of duties, subtle signs of fatigue or altered appearance in state media footage.

Also, commentary notes that in China the health of the top leader is extremely opaque and internal reporting systems (“neican” internal bulletins) may carry unreported assessments. - Some of the published rumour-articles cite Chinese-language forums or “self-media” (people posting anonymously) claims, but those are by definition anecdotal and cannot be independently verified. For example, one article states:

“According to insiders, Xi’s prior medical history supports repeated strokes.”

· Xi is approximately 70 years old (born June 1953).

· He appears overweight, with visible abdominal obesity and mild stiffness of movement.

· His gait has occasionally been described as careful or slightly uneven, noted during long parades and reviews of troops.

· Xi is known to be a non-smoker and a moderate drinker, unlike several previous Chinese leaders.

· According to official hagiographies, he swims regularly and maintains “a disciplined lifestyle,” though such claims are political messaging rather than verified fact.

In 2012 there were rumours that Absence in early September 2012 (just before his becoming General Secretary) led to speculation of a back injury or minor heart issue.

In 2017 onward General pattern of health-rumours (incl. fatigue, limited appearances) emerging repeatedly in exile Chinese media and “self-media. Because China’s leadership rarely publishes medical details, gaps lead to speculation.

In 2021–2022 Rumour of a cerebral aneurysm / brain aneurysm that Xi might be suffering from, choosing non-surgical treatment or traditional medicines. Based on tabloid or less-reliable sources; no official evidence.

In Mid-2024 Rumours that Xi had suffered a stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), especially after a period of fewer public appearances. Fact-checkers (e.g., Reuters) debunked specific stroke claims.

Key Rumours

🧭 Additional Context & Credibility

- The rumour of a “stroke” in July 2024: The widely circulated images claiming this were mis-captioned and Reuters found no credible confirmation

- The aneurysm rumours: Some media reported that Xi was diagnosed with an aneurysm and avoided surgery. But these come largely from tabloid style reports and are not corroborated.

- Expert commentary: Scholars note that because China tightly controls information about top-leader health, rumours fill the vacuum when Xi’s public profile changes (gait, appearances, delegation patterns).

- Some of the rumours may be information operations or “noise” leveraged by foreign actors to exploit China’s opacity. For example, one analysis says rumours of Xi’s health issues “lack credible evidence and stem from opportunistic sources”. lansinginstitute.org

Assessment

- These rumours should be treated as hypotheses, not fact. There is no verifiable official disclosure about serious health problems for Xi.

- Because Xi is ageing (born June 1953) and holds extremely demanding roles, it is plausible he may have age-related health issues (e.g., cardiovascular, musculoskeletal) — but none of the specific dramatic rumours (stroke, aneurysm) have solid public proof.

- The larger significance is not the health condition itself, but what the rumours reveal: the sensitivity of the Chinese system to leader physical condition, the role of public appearances as symbolic signals, and how absences or changes provoke speculation about power dynamics.

- When Xi deviates from normal visibility, it raises questions—not just about health, but about succession, factional contestation, and institutional stress.

⚠️ Credibility and Limitations

- The Chinese state and official media have not confirmed any illness or medical condition for Xi.

- Many of the health reports are anonymous, speculative, or based on third-hand sources (forums, “insiders”, self-media).

- As the Reuters fact-check shows, even widely circulated images and claims about a stroke were debunked

- Because of the highly centralised and censored information environment in China, absence of public evidencedoesn’t necessarily indicate absence of symptoms; similarly, absence of confirmation should not be taken as proof of a serious condition.

- The rumours often have political motivations, both inside China (factional signalling) and outside China (media speculation about succession or instability). Analysts often warn against treating them as verified fact

Key Assessments / Themes

- Stroke / cerebrovascular event: A recurring theme; some sources claim Xi had one in July 2024, then another in 2025.

- Reduced leadership visibility / delegation: Some observers point to Xi allowing other senior officials to travel or publicly perform tasks he would normally handle.

- Succession anxiety: Analysts link health-rumours to broader questions of how the Chinese Communist Party handles transition, since Xi abolished term limits and concentrated power, leaving little visible succession planning

- Use of symbolism and media editing: Some speculation that state media is tightly controlling Xi’s appearances—and that signs of fatigue or altered gait are being edited or concealed

Given the information:

- The evidence for a major, publicly acknowledged health crisis for Xi is weak—there are strong rumours, but no credible, independently confirmed medical diagnosis.

- The multiple reports and rumours suggest that health is a plausible risk factor for the Chinese leadership structure, but one must treat the claim as speculative.

- The stronger signal is not necessarily the health condition itself, but the political and institutional implications: the fact that rumours proliferate may signal internal uncertainty, or that the regime perceives a risk and seeks to manage image.

- For an analytic paper: you can treat this topic as a “risk scenario” rather than a confirmed fact. That is, assume “if health issues” (rather than “because health issues”). Use it as a lens to explore structural resilience rather than as a firm medical finding.

2. Signals and Narratives Around Xi’s Health

Western intelligence agencies and Asian diplomatic sources have intermittently noted Xi’s fatigue and limited mobility during high-profile events, such as long ceremonial parades and extended foreign trips. Tese observations, though inconclusive, reflect broader uncertainty about Xi’s long-term physical resilience rather than concrete medical evidence.

Chinese state media’s increasingly controlled coverage—showing shorter, highly choreographed public appearances—mirrors earlier stages of image management used for aging party elders, such as Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin in their later years. Moreover, delegation of ceremonial duties to Premier Li Qiang and Politburo Standing Committee members has become more pronounced, a subtle signal that the CCP may be testing limited decentralization to prepare for continuity scenarios.

3. Succession Anxiety Within the CCP

Xi’s decision to abolish presidential term limits in 2018 dismantled the institutionalized succession model that Deng Xiaoping designed to prevent power struggles. Consequently, no clear heir apparent exists. If Xi’s health were to deteriorate significantly, the Party would face its first unstructured transition in decades—potentially igniting factional contestation between:

- The “New Fujian” bloc, loyal to Xi’s provincial network and security apparatus;

- The technocratic faction, oriented around Premier Li Qiang and economic pragmatists seeking market stability;

- The “Princeling” conservatives, advocating ideological purity and continuity of Xi’s nationalist course.

In such a vacuum, institutions like the Central Military Commission (CMC) and the Central Guard Bureau would play a decisive role in determining political continuity, possibly prioritizing regime survival over reform.

4. Impact on Policy Continuity and Strategic Behavior

A weakening leader often produces policy rigidity. Bureaucrats avoid innovation for fear of crossing unspoken red lines, while elites compete in displays of loyalty rather than competence.

In Xi’s case, this could translate into:

- Economic paralysis, as policymakers hesitate to propose bold stimulus measures amid an unpredictable power environment;

- Increased external assertiveness, with nationalist actions—especially in the Taiwan Strait or South China Sea—used to demonstrate political vitality and suppress perceptions of weakness;

- Intensified internal repression, particularly targeting dissent within the party and digital spheres, to project unity.

Such dynamics recall the late-Brezhnev period in the USSR, when a leader’s declining health produced strategic overreach and institutional decay beneath an image of stability.

5. Foreign Policy Consequences

Externally, Xi’s perceived frailty could reshape China’s diplomatic tempo. Allies and adversaries alike would test Beijing’s coherence:

- Washington may interpret internal uncertainty as an opportunity to strengthen deterrence coalitions around Taiwan.

- Moscow, already dependent on Beijing for economic lifelines, might worry about the continuity of the China–Russia axis.

- Southeast Asian states could accelerate hedging strategies, balancing between Beijing and Washington amid doubts over China’s internal cohesion.

Meanwhile, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), long cultivated as a personalist institution loyal to Xi, may seek greater autonomy under the pretext of “continuity of command,” subtly shifting the balance of civil–military relations inside the regime.

Scenario — Health-Driven Power Transition Risks (2025–2030)

Scenario A. Controlled Transition. Xi remains nominally in power but gradually transfers functions to a loyal successor (Li Qiang or a security chief). 40% Probability. Maintains short-term stability, slows policy innovation.

Scenario B. Silent Regency. Xi’s health deteriorates sharply; an inner circle governs through informal collective decision-making. Probability: 30%. Factional friction increases; foreign policy becomes reactive.

Scenario C. Crisis of Succession. Sudden incapacity or death triggers internal CCP struggle over legitimacy and command. Probability : 20%. Major instability; risk of regional miscalculations or internal purges.

Scenario D. Managed Mythology. Xi’s limited capacity is concealed through symbolic appearances while the system continues unchanged. Probability: 10%. Long-term stagnation; policy drift similar to late Soviet stagnation.

7. Conclusion — The Myth of the Indispensable Leader

Whether Xi Jinping enjoys robust health or faces hidden ailments, the centralization of authority around one man has already created structural vulnerability. The absence of transparent succession planning, combined with heavy reliance on personal loyalty, makes China’s governance brittle to shocks—be they political, economic, or biological.

As history shows—from Mao’s final years to the Soviet gerontocracy—the myth of the indispensable leader often becomes the regime’s greatest weakness. If Xi’s health truly falters, China’s political system will face its most consequential stress test since 1989: not merely whether it can survive without him, but whether it can evolve beyond him.