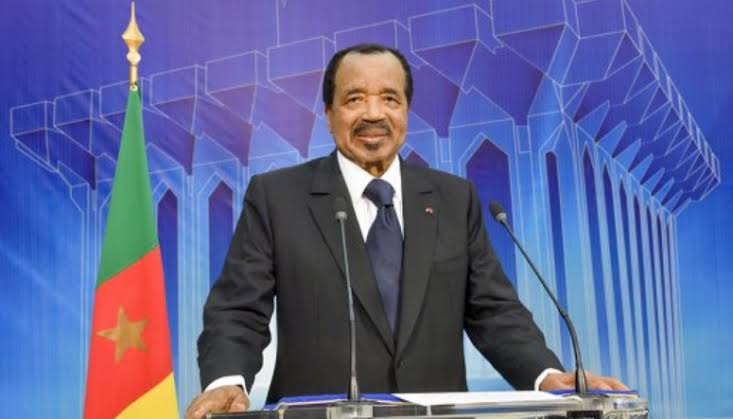

Cameroon’s Constitutional Council declared 92-year-old President Paul Biya the winner of the October 12, 2025 presidential election, securing 53.66% of the vote. Biya, Africa’s oldest and one of its longest-ruling leaders, thus earned an eighth term in office, extending his 43-year rule until at least 2032. The council announced opposition candidate Issa Tchiroma Bakary as runner-up with 35.19%. Biya’s victory means Cameroon will continue under the only president most citizens have ever known, as he first assumed power in 1982 after the resignation of the country’s founding leader.

President Biya and his ruling Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM) hailed the outcome as a renewed mandate. In a statement after the results, Biya thanked the people for placing their trust in his leadership once again and expressed sorrow over post-election violence. He offered condolences to “all those who have unnecessarily lost their lives” in unrest surrounding the vote. The government dismissed accusations of fraud, insisting the electoral process was “peaceful” and urging citizens to respect the official outcome. Government officials and ministers celebrated Biya’s win in stronghold regions, even as security forces maintained a heavy presence in opposition centers. Territorial Administration Minister Paul Atanga Nji blamed the opposition for the turbulence, accusing “criminal” protesters of “wreak[ing] havoc” and causing their own casualties during illegal demonstrations. The government’s narrative painted the unrest as an insurrection orchestrated by the opposition, announcing investigations into Issa Tchiroma for allegedly inciting violence.

Opposition Reaction: The opposition has roundly rejected the official results, denouncing the election as fraudulent and illegitimate. Issa Tchiroma Bakary – a former Biya ally turned opposition coalition candidate – declared himself the true winner even before the official tally was released, claiming he had secured 55% of votes and warning that Biya must “accept the truth of the ballot box” or “plunge the country into turmoil”. After the Constitutional Council’s announcement, Tchiroma castigated the authorities for proclaiming “truncated results” and awarding Biya a “fictitious victory”, vowing to challenge what he views as a stolen mandate. Other opposition figures echoed this rejection: Akere Muna, a prominent lawyer and former candidate who joined Tchiroma’s coalition, condemned the process as “fraudulent” and the Constitutional Council as “nothing more than the rubber stamp of a tyranny”. The lone female candidate, Tomaïno Ndam Njoya (fifth place), likewise asserted the outcome did not reflect the people’s will, citing “irregularities, manipulation and repeated violations of the law” in the election. Even some ordinary voters in urban centers described Biya’s re-election as “a stolen victory”, noting that after over four decades of the same government, “the people did not choose Paul Biya”. However, not all opposition figures held the same line – for instance, Cabral Libii (a third-place candidate) broke ranks by congratulating Biya on his victory, underscoring divisions among regime opponents.

Internationally, reactions were mixed but cautious. Many global leaders were initially quiet in the immediate aftermath of the disputed result. The European Union voiced “deep concern” over reports of violent repression of protests, urging Cameroonian authorities to rein in excessive force and engage in dialogue to preserve stability. The United Nations Secretary-General echoed these concerns, calling on all political stakeholders to exercise restraint, avoid inflammatory rhetoric, and pursue peaceful avenues to resolve disputes. Prominent human rights groups, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, condemned the “excessive use of force”against demonstrators and called for an impartial investigation into civilian deaths. At the same time, the African Union (AU) moved quickly to congratulate Paul Biya on his re-election, effectively recognizing the result. AU Commission Chairperson Mahamat Ali Youssouf offered Biya his congratulations while simultaneously expressing grave concern over the post-election violence and urging an “inclusive national dialogue” to address political grievances. This tempered AU stance – endorsing the official winner but advising dialogue – reflects the broader regional approach of prioritizing stability and incumbency. Other African leaders in Central Africa, many of whom lead similarly long-ruling regimes, also favored continuity in Cameroon and have historically been reluctant to criticize Biya’s electoral processes.

Allegations of Irregularities and Public Protests

Despite the official pronouncement, serious irregularities and manipulation marred the 2025 polls, according to opposition and civil society observers. A coalition of eight local civil society organizations documented numerous red flags: names of deceased citizens on voter rolls, unequal distribution of ballot papers favoring regime strongholds, and even attempted ballot box stuffing in some areas. Opposition parties reported that in parts of the country, especially rural government-controlled areas, some voters were coerced or multiple voting was allowed with the complicity of polling officials. Notably, authorities barred a major opposition leader, Maurice Kamto, from running well before election day. Kamto – who was the runner-up in 2018 – was disqualified by the Constitutional Council, removing one of Biya’s most popular challengers from the race and raising doubts about the inclusiveness of the contest. These actions, along with the state’s tight grip on the Elections Cameroon body, cast a long shadow over the integrity of the vote.

Irregularities were especially glaring in Cameroon’s conflict-torn Anglophone regions. The North-West and South-West regions, wracked by an ongoing separatist insurgency, saw widespread abstention due to insecurity – yet the official results bizarrely reported about 53% turnout there and landslide tallies for Biya (around 68–86% of the vote in those regions). Given that armed separatist groups had violently enforced a boycott of any election activities, such high turnout and overwhelming pro-Biya margins in these warzones struck observers as “implausible” and evidence of fraud. As Akere Muna noted, it defies credibility that Biya “won in certain war zones” where most residents could not safely vote. Even some government allies tacitly acknowledged irregularities: the African Union’s election observation mission rather controversially declared the vote was “largely in accordance”with international standards, but domestic monitors vehemently disagreed. The disconnect between the AU’s positive assessment and local reports of malpractice has fueled public cynicism.

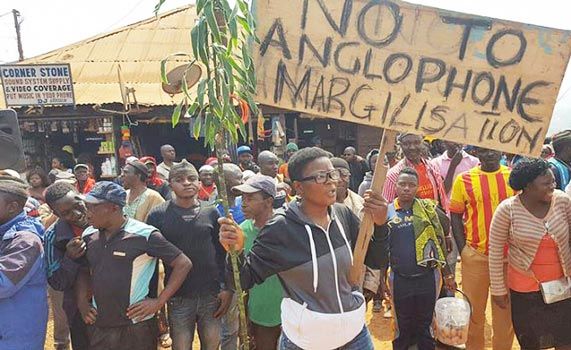

Allegations of a rigged election rapidly spilled into the streets. Widespread protests erupted in major cities like Douala (the commercial hub), the capital Yaoundé, and regional towns such as Garoua and Bafoussam immediately after partial results hinted at a Biya victory. Demonstrators – largely youth and opposition supporters – defied official bans to vent their anger, chanting that the vote was “stolen” and setting up barricades of burning tires and debris. Clashes broke out as riot police and gendarmes deployed tear gas, water cannons, and in some instances live ammunition to disperse crowds. In Douala’s New Bell neighborhood and elsewhere, protesters fought back with sticks and stones, and even attacked police stations, reflecting a level of desperation and rage not seen in recent elections. Over several days of unrest (October 26–28), the opposition reported that at least 6 people were killed – four protesters shot dead over the weekend and two more on Monday – and hundreds were arrested amid the crackdown. Officials confirmed four fatalities in Douala alone while claiming security forces also suffered injuries in the melees. Significantly, gunfire erupted in the northern city of Garoua near Tchiroma’s residence on the day results were confirmed, with Tchiroma alleging that two civilians were shot dead by forces outside his home. This volatile situation prompted local authorities to impose curfews and flood the streets with troops to regain control. By October 29, the immediate protests had been largely quelled by heavy rain and an intimidating security presence, though at the cost of a tense quiet in normally bustling cities.

The government’s hardline response has drawn domestic and international condemnation. Opposition leaders accuse the regime of excessive, lethal force, noting that protesters were largely unarmed and exercising their right to demand transparency. Human rights activists point to Cameroon’s past pattern of repressing post-election dissent – as seen after the 2018 vote – and fear a repeat mass-arrest of opposition figures. Indeed, even before results were announced, authorities preemptively detained prominent members of Tchiroma’s coalition (such as Anicet Ekane and Djeukam Tchameni) on charges of plotting violence. The Minister of Administration, Atanga Nji, has ominously warned that Tchiroma’s “calls for insurrection” will face legal consequences, signaling that the leading opposition figure could be arrested or prosecuted for contesting Biya’s win. These developments suggest that the regime is prepared to criminalize dissent rather than address the underlying grievances about electoral fairness. For now, calm has been forcibly restored, but the political standoff remains unresolved – opposition groups refuse to recognize Biya’s victory, while the government refuses to entertain any challenge to the result. This fraught impasse raises urgent questions about Cameroon’s governance, stability, and unity in the aftermath of the election.

The short-term consequences of the disputed election have been a further erosion of political trust and a tightening of authoritarian controls. In the immediate wake of Biya’s contested victory, Cameroon faces heightened instability. The turmoil on the streets – though temporarily suppressed – signals a potentially prolonged post-election standoff between an emboldened regime and an aggrieved opposition. The violent crackdowns have deepened opposition bitterness and could radicalize segments of the population who see no peaceful outlet for political change. Governance is likely to become even more securitized in the short run: with protests flaring, Biya’s government has leaned heavily on the military and police to enforce order, which may come at the expense of civil liberties. Reports already indicate sweeping arrests of protest organizers, expanded use of military courts for civilians, and increased checkpoints in restive areas. Opposition activities are being driven underground, as public demonstrations are banned and leading activists risk imprisonment. Such measures consolidate Biya’s grip in the near term but undermine the legitimacy of governance, as a large portion of the populace perceives the government as having no genuine mandate.

Politically, the election outcome and subsequent repression may extinguish what little reform momentum existed. Biya campaigned minimally and offered no new policy vision aside from promises that “the best is still to come” despite acknowledged challenges. With his re-election secured amid controversy, there is scant incentive for the regime to pursue meaningful reforms in governance or economic management. Instead, early signs point to continuity of the status quo: the same aging inner circle and patronage networks are likely to remain in charge. President Biya is renowned for his absentee leadership – often spending long stretches abroad (frequently in Switzerland for private visits or medical care) – and this pattern is expected to persist, possibly worsening administrative paralysis. Indeed, critics note that Biya held only a single campaign rally and has rarely appeared in public, fueling concerns about an absent ruler presiding over a stagnant bureaucracy. In the short run, real governance is often delegated to a small coterie of loyalists and security chiefs, whose focus will be on quelling dissent rather than undertaking inclusive policymaking.

One immediate repercussion is likely a harsher climate for political freedoms. Cameroon had already seen a rollback of democratic space in recent years – opposition meetings are frequently banned, journalists and activists face intimidation, and in 2020 the government outlawed protests by Kamto’s party, detaining hundreds. Now, with the regime feeling threatened by post-election unrest, it could double down on authoritarian tactics. Opposition leaders fear a wave of retributive arrests and trials. We can expect continued detention of outspoken figures (some 3,000 Cameroonians were already in prison for political reasons even before the election), gagging of independent media, and perhaps new legislation under the banner of “security” to restrict online mobilization or public assembly. These moves would further entrench authoritarian rule and could push Cameroon toward a de facto one-party state, at least in practice. The risk of authoritarian consolidation is high: having removed term limits in 2008 and now weathered another contested poll, Biya’s regime may feel empowered to eliminate remaining checks (for example, by neutering opposition parties or civic groups).

However, this hardline approach carries significant risks for political stability and national unity. The immediate stability is fragile – while the streets may be quiet for now, the grievances that sparked protests remain unaddressed. Many Cameroonians—especially the urban youth and educated classes—are deeply frustrated by what they see as decades of misrule and corruption. As one Douala resident put it, “for 43 years… this government has brought us nothing. Nothing at all”. Such disillusionment suggests that public anger could erupt again, perhaps spontaneously or around future flashpoints (e.g. the next economic crisis or a symbolic event like Biya’s swearing-in). Indeed, some analysts predict that unrest will escalate further: “Cameroonians widely reject the official result, and we cannot see the Biya government lasting much longer,” warned one political economist, suggesting that sustained popular rejection might make the country “ungovernable” for the regime. While that remains to be seen, the mere fact such scenarios are being voiced underlines the volatile atmosphere. In the short term, Cameroon faces a governing paradox: enforcing calm through force may prevent immediate chaos, but it also deepens the fissures that could lead to greater upheaval down the line.

Long-Term Consequences and Future Political Scenarios

Looking beyond the present crisis, the long-term consequences of this election’s outcome raise profound questions about Cameroon’s political future. With Paul Biya possibly in power until age 99 (the end of this new term in 2032), Cameroon’s political system risks entering an unprecedented twilight of gerontocracy and uncertainty. The country is effectively staring at a succession dilemma. Biya’s continued reign without a clear transition plan sets the stage for a potential power vacuum or crisis when he eventually exits the scene. As analysts have long warned, the very strength of Biya’s hold on power may prove its greatest weakness – “Biya’s hold on power could lead to instability when he eventually goes,” observers note. Having ruled by concentrating authority in the presidency and sidelining institutional checks, Biya leaves no obvious mechanism for an orderly succession. This is a recipe for elite infighting and turmoil in a post-Biya scenario.

One likely development to watch is constitutional reform – not to liberalize, but rather to manage succession. Cameroon’s constitution, as it stands, designates the Speaker of the Senate as interim president in the event of a vacancy, with a new election to be held within 90 days. However, that framework may not suit those in Biya’s inner circle who wish to maintain continuity (especially if Biya were to become incapacitated suddenly). There has been increasing chatter in Cameroonian political circles about introducing a vice-presidential post or similar arrangements to better prepare for a handover. Although no official announcement has been made, President Biya has “quietly laid the groundwork for dynastic succession”, according to political observers. His 53-year-old son, Franck Biya, has no formal office but has built a network of allies and influence behind the scenes, and is widely believed to be the anointed heir should the opportunity arise. In the lead-up to the election, whispers of a “Franck Biya succession plan” grew louder – a campaign-style photo of Franck even circulated briefly online before being withdrawn. This suggests that regime insiders are positioning for a dynastic transfer, akin to patterns in other Central African autocracies (Gabon, Togo, Chad, etc.), albeit in Biya’s typically opaque style.

If regime continuity through family succession is pursued, Cameroon could essentially see a handover from father to son rather than a genuine political opening. Such an outcome would likely require behind-the-scenes constitutional tweaks or rulings by the loyal Constitutional Council to smooth Franck Biya’s path. It would mean an extension of the Biya era under a new face, with the ruling party and military-intelligence apparatus remaining intact. While this might avert an immediate power vacuum, it carries the risk of backlash: many Cameroonians are wary of a “president-for-life” scenario extending into a familial dynasty. As one social justice campaigner noted, “Biya’s approach is designed to keep everyone guessing”, but the lack of transparency leaves the country “uncertain about its future”, and an opaque father-to-son transition could trigger internal splits or public outrage. Already, Cameroon’s political trajectory fits into a regional pattern where entrenched rulers change constitutions and use institutions to cling to power indefinitely. Authoritarian consolidation in this form – effectively institutionalizing a long-term presidency with a family succession – would undermine any hope for democratic renewal.

On the other hand, there are scenarios of potential regime change to consider, however remote they might seem now. Should public discontent continue to mount, one cannot completely rule out more dramatic outcomes in the long run. For instance, if sustained protests or civil resistance campaigns grow (as hinted by movements like the diaspora-led “1 Million Strong – Paul Biya Must Go” hashtag campaign that gained significant traction), the regime could face a legitimacy crisis. A prolonged popular uprising would likely be met with force, but in extreme cases might spur factions within the military or ruling elite to intervene. The specter of a palace coup or internal succession – where key army or party figures move to replace Biya to save the system – is another possibility often whispered in Yaoundé. So far, Biya has maintained loyalty through patronage and a fragmented security structure, but a chaotic transfer or a steep decline in stability (especially if Biya’s health falters) could test that loyalty. Additionally, Cameroon is part of Africa’s broader “coup belt” region (neighboring Chad and Central African Republic have seen putsches or civil wars). While Cameroon’s military has remained outwardly loyal, a crisis of succession could tempt ambitious generals, especially if they fear losing influence in a post-Biya shakeup.

Another long-term scenario revolves around the “implosion” vs. “inertia” . For many years, Cameroon’s system has survived through inertia – a combination of public resignation, fragmented opposition, and the regime’s adept survival tactics. But this election suggests inertia is reaching its limits: economic stagnation, youth unemployment, and multiple conflicts are brewing a volatile mix. A more hopeful long-term scenario would involve gradual change through dialogue and reform, though this currently appears elusive. International actors and some domestic voices are calling for an “inclusive national dialogue” after the election In theory, Biya (or his successor) could opt to initiate political reforms – such as reintroducing term limits, overhauling the electoral commission for credibility, or devolving some power to regions – as a means to ease tensions and leave a controlled legacy. There is also speculation that Biya might, at some midpoint, voluntarily step down or hand over if assured of safety and his legacy (for instance, some have floated the idea of him resigning partway through the term in favor of a chosen successor who then contests an election). While Biya has given little indication of such intentions, the heavy international spotlight and the apparent public rejection of his mandate might pressure the regime to consider at least cosmetic reforms. What is clear is that Cameroon’s political future is at a crossroads: it will either see the continuation of the existing regime through dynastic succession and deeper authoritarianism, or face a disruptive change (be it through uprising, internal power shift, or negotiated transition). Each scenario carries high stakes for governance, stability, and the well-being of Cameroon’s 30 million people.

Ethnic Dynamics and National Unity Challenges

Ethnicity has long been a sensitive fault line in Cameroonian politics, and the 2025 election has underscored and potentially aggravated those ethno-regional tensions. The major groups often mentioned – the Beti (including Biya’s Beti/Bulu ethnic group from the South), the Bamiléké (a populous highland group in the West), and the Anglophone communities (largely in the North-West and South-West) – each have distinct historical grievances and political alignments. Biya’s power base is largely drawn from his Beti kinsmen of the Centre-South regions and a network of allied groups from the Francophone elite, including some northerners. In contrast, the Bamiléké and many Anglophones have frequently been associated with opposition to Biya’s rule, feeling excluded from true power. This election, like the disputed 2018 vote, has been accompanied by a “worrying ethnic dimension” to political tensions. The aftermath of the 2018 election saw escalating hate speech and division “between Biya’s supporters, on one hand, and those of his chief opponent Kamto, on the other”. Maurice Kamto, who hails from the Bamiléké community, became a target of ethnic chauvinism – pro-regime voices cast his challenge as a Bamiléké attempt to usurp power, leading to poisonous rhetoric on social media and even threats against that community. In 2025, with Kamto barred, Issa Tchiroma’s candidacy somewhat altered the ethnic calculus – Tchiroma is from the northern (Fulani) community – but many of his supporters in the opposition coalition were from western (Bamiléké) and southern minority groups united mainly by anti-Biya sentiment. Thus, the ethnic undertones persisted: regime loyalists quietly cautioned against “enemies from the West” (a coded reference to Bamilékés), while opposition activists accused Biya’s predominantly Beti ruling clique of holding the country hostage.

The Beti elite around Biya have reasons to be wary. They have disproportionately benefited from Biya’s patronage – occupying top positions in government, military, and state companies – and fear that a loss of power could mean loss of privilege or even retribution. This has fostered a siege mentality among some pro-Biya circles, which can translate into ethnic distrust. For instance, security crackdowns after protests often target neighborhoods or regions identified with opposition ethnic groups (e.g. security forces deploying heavily in Bamiléké-majority cities like Bafoussam during unrest). Such actions risk entrenching communal resentments. The Bamiléké, known for their commercial acumen and having a significant diaspora, feel politically marginalized since independence. No Bamiléké has ever held the presidency; indeed, the early post-colonial era saw brutal repression of Bamiléké-led opposition (the UPC rebellion of the 1960s). Kamto’s rise in 2018 briefly galvanized Bamiléké hopes for representation at the highest level, but the regime’s harsh response (including Kamto’s post-election arrest in 2019) was perceived by many as not just political but also ethnically tinged repression. In 2025, many Bamiléké voters likely supported the Union for Change coalition and now see the election outcome as yet another denial of their community’s aspirations. There is a risk that inter-ethnic mistrust could deepen, particularly between some Beti and Bamiléké citizens, if the regime uses “divide-and-rule” tactics – for example, scapegoating the Bamiléké for protest violence or painting the opposition as an ethnically driven movement. Already, diaspora activists lament “rising tribalism” in discourse, noting that corruption and poor governance are sometimes blamed on ethnic groups rather than the regime’s policies. This kind of rhetoric, if unchecked, could fray the delicate national unity Cameroon has managed to maintain among its dozens of ethnic groups.

By far the most acute ethno-political challenge remains the Anglophone crisis. Anglophone Cameroonians (largely from the North-West and South-West regions) have felt increasingly marginalized by the Francophone-dominated state for decades. Grievances over the use of French in courts and schools and perceptions of second-class treatment erupted in 2016–17 into mass protests, to which the Biya government responded with force and internet shutdowns. This escalated into a full-blown secessionist armed insurgency seeking an independent state of “Ambazonia” in the Anglophone regions. The conflict has killed nearly 7,000 people (mostly civilians) and displaced over a million, with atrocities by both separatists and the military. The 2025 election was the first presidential poll since this war intensified, and it was essentially non-participatory in much of the Anglophone zones. Separatist militants warned civilians to boycott the vote, enforcing this with violence. As noted, the official turnout figures there (53%) are viewed as grossly inflated. Such manufactured results not only call the election into question but also further alienate Anglophones – it shows the state proceeding as if the war-torn regions’ voices simply don’t matter (or can be invented). Anglophone leaders and communities are likely to interpret Biya’s re-election as a sign that no change will come via national politics, possibly hardening separatist resolve. Indeed, many Anglophones already feel that the predominantly Francophone regime is uninterested in a genuine resolution; the government has largely pursued a military solution while offering a limited decentralization plan that fell short of demands. The election outcome – keeping the same leadership – signals continuity of the hard line. In practical terms, the Anglophone conflict is set to continue or even escalate. Biya’s government may intensify military operations against separatist fighters, especially if it believes international scrutiny is distracted by the electoral controversy. This means more violence in those regions and a sustained humanitarian crisis. Moreover, any national dialogue that might be convened post-election (as AU and others urge) must tackle the Anglophone issue, or it will be seen as window dressing. Without addressing Anglophone grievances, Cameroon’s national unity remains deeply fractured.

Ethnic dynamics also intersect with economic and regional disparities. The Far North (largely Fulani, Hausa, and other Muslim communities), for example, has suffered from Boko Haram terrorism and extreme poverty. Voter turnout there was historically high for Biya, thanks to local elites’ support, but discontent simmers beneath the surface due to underdevelopment. Issa Tchiroma being from the North may have peeled away some northern support from Biya, which could unsettle the traditional ethnic alliance between northern Muslim elites and Biya’s southern Christian base that has held since the first President (Ahmadou Ahidjo, a northerner) ceded power to Biya. If the North feels that even their own elites can’t gain power through elections, it could revive old north-south tensions. Cameroon’s delicate ethnic balancing act – often touted by the regime as “national unity” – is under strain. Kah Walla, an opposition leader, points out that Biya inherited a relatively peaceful, cohesive society, yet today armed groups are active in 5 of 10 regions along ethnic or regional lines. This includes Anglophone separatists, Boko Haram (an Islamist insurgency mainly in Far North), and local inter-ethnic clashes (such as farmer-herder conflicts taking ethnic dimensions). The election’s divisive aftermath could exacerbate each of these if not carefully managed. For instance, “rising tribalism” has been noted as both a symptom and a weapon – public frustration sometimes manifests as blaming other ethnic groups for the country’s woes. The longer genuine political reform is delayed, the more space for ethno-regional entrepreneurs to fuel resentments as they jockey for power in a post-Biya scramble.

In summary, Cameroon’s 2025 election result may deepen the ethnic fault lines. The Beti-dominated regime appears to cling to power at any cost, the largely Bamiléké-supported opposition feels cheated once again, and the Anglophone minority sees little hope from the Francophone political system. National unity – once a proud element of Cameroon’s identity – is now fragile. Without deliberate efforts at ethnic reconciliation and inclusive governance (e.g. fair power-sharing, cultural recognition, and justice for regions in conflict), the country risks sliding into more sectarian discord. The challenge for Cameroon is to prevent political rivalries from becoming ethnic vendettas. Unfortunately, as long as the winner-takes-all dynamic persists under Biya, ethnic communities will perceive the stakes as existential – making politics a zero-sum game between groups, rather than a unifying national project.

International Reactions and Geopolitical Implications

The outcome of Cameroon’s presidential election has also drawn the attention of foreign powers, each assessing how the continued rule of Paul Biya aligns with their interests. France, the former colonial power, has historically been Cameroon’s closest ally and has generally favored continuity and stability over democratization. In this instance, Paris has maintained a low profile publicly, refraining from overt criticism of the election. French officials have long been reluctant to challenge Biya, whose regime has ensured French economic interests (from oil to infrastructure contracts) and security cooperation in the region. It is widely understood that France stands to benefit from Biya’s staying power: the existing diplomatic and economic arrangements remain intact. While French diplomats privately express concern about Cameroon’s instability, they are likely relieved that a friendly regime endures, forestalling any abrupt shift that might invite anti-French sentiment or losses for French businesses. Indeed, Cameroon under Biya has been a reliable partner in the French sphere of influence in Central Africa. President Emmanuel Macron in recent years walked a cautious line – even as he acknowledged France’s past wrongdoings in Cameroon’s colonial war, he stopped short of pushing for political change in Yaoundé. With Biya’s re-election, France will likely continue quiet engagement, possibly encouraging dialogue to calm tensions, but ultimately prioritizing the status quo that safeguards its interests.

China has in the past two decades become one of Cameroon’s most significant partners, and it too benefits from regime continuity. China stands to gain by solidifying its economic foothold – a continuation of Biya’s rule ensures Chinese loans will be honored and new deals can be struck without fear of a nationalist or Western-oriented pivot in Yaoundé. Chinese officials will encourage calm but are unlikely to push for political reforms, making them comfortable external stakeholders in an ongoing Biya presidency.

Russia sees an opportunity in Cameroon’s post-election landscape as well. In recent years, especially since 2022, Cameroon has inched closer to Moscow’s orbit for security cooperation. In April 2022, Yaoundé and Moscow signed a new military cooperation agreement covering training, arms procurement, and intelligence sharing. A friendly Biya regime could grant Russia greater access – whether for arms sales (Cameroon might diversify from mostly Western weapons to Russian equipment) or political support (Cameroon could back Russia in international forums). Geopolitically, Russia benefits if Cameroon distances from Western influence, and continued Biya rule might facilitate that given Biya’s comfort with authoritarian partners. If Western pressure mounts over the election fallout, Biya has the option to invite more Russian security “advisers” or form new agreements, under the guise of combating terrorism or protecting sovereignty. This dynamic was seen in other African states under sanction or criticism, and Cameroon could follow suit, thereby enhancing Russia’s regional leverage.

The United States and other Western nations (like the UK and Germany) have a more complicated stake. The U.S. has a strategic interest in Cameroon due to counterterrorism (the fight against Boko Haram/ISIS-West Africa in the Lake Chad Basin) and regional security, but it also professes support for democracy and human rights. Washington in recent years reduced some military aid to Cameroon citing abuses in the Anglophone regions, and it has pressed for dialogue to resolve that conflict. The contentious 2025 election puts the U.S. in a familiar bind: condemn electoral malpractice and risk alienating a counterterrorism partner, or mute criticism to maintain cooperation. So far, U.S. officials have limited themselves to expressing concern over the violence and urging peaceful resolution. It’s unlikely the U.S. will outright sanction Cameroon’s government over a flawed election (especially given Cameroon is not as high-profile as other cases, and there are competing crises globally). However, U.S. leverage may diminish as Biya looks elsewhere for support. The outcome arguably benefits U.S. rivals: China and Russia, as noted, and even countries like Turkiyye (through TRT Afrika, Turkey signaled interest in African affairs including Cameroon) or Middle Eastern states that might offer investment without governance strings. Western influence in Yaoundé has been waning, and another seven years of Biya likely cements that trend.

Regional blocs and neighbors have reacted largely in favor of continuity. Cameroon’s immediate region (Central Africa) is dominated by long-serving leaders who have little appetite for challenging election outcomes (for fear of setting precedents). The Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) are expected to endorse Biya’s win or at least work with his government. Regional powers like Nigeria, which borders Cameroon to the west, have a keen interest in a stable Cameroon but traditionally avoid intervening in its politics. Nigeria’s President may privately worry that a restive Cameroon (especially with the Anglophone conflict spilling refugees and separatists into Nigeria) could pose security and economic headaches. Yet, Nigeria and other neighbors (Chad, Gabon, Congo) are likely quietly relieved that a known quantity – Biya – remains at the helm, rather than an unpredictable change. No African Union member state has openly challenged the result, and indeed the AU’s congratulatory message confirms the continental preference for stability. One could contrast this with West Africa’s ECOWAS, which in recent years took harder stands against unconstitutional power grabs; Central Africa lacks such activist regional mechanisms. Thus, the region as a whole benefits from avoiding a crisis in Cameroon: a sudden collapse or conflict there could destabilize trade and send shockwaves (for instance, Cameroon is a key transit route for landlocked neighbors like Chad and CAR). In maintaining business as usual with Biya, regional actors hope to keep a lid on potential cross-border troubles.

That said, who benefits internationally from Biya’s victory can also be seen in terms of great power rivalry. Given the global context (with heightened US-China competition and Russia’s assertiveness in Africa), Biya’s Cameroon becomes a chessboard piece. China emerges as a clear winner – it retains a pliant partner rich in natural resources (oil, timber, minerals) and strategic location (Gulf of Guinea coast). Russia also wins an opening to expand influence at the expense of Western clout. France preserves its Francophone sphere ally. By contrast, pro-democracy forces internationally see a setback – Cameroon under Biya will likely not join the recent trend of African nations pushing back against entrenched leaders (to the contrary, it bucks the trend of change seen in places like Zambia or Malawi in recent years). The United States and EU face the awkward task of engaging with a regime they’ve implicitly criticized; their counterterrorism and regional goals may force them to work with Biya, but doing so could be seen as condoning authoritarian entrenchment. Notably, global attention on Cameroon’s plight can be fickle – with many crises worldwide, Cameroon has often been “largely ignored by the international community”, as one analyst put it. This relative neglect has been an advantage for Biya, allowing him to rule repressively without sustained external pressure. The post-election fallout might bring a short-lived spotlight (e.g., statements of concern), but unless the situation deteriorates dramatically, it is likely that major powers will continue to prioritize their strategic interests over Cameroon’s democratic development.

foreign actors’ responses reflect a pragmatic acceptance of Biya’s re-election. Calls for investigations or dialogue notwithstanding, there is no sign of concerted external action to challenge the outcome. Instead, those who benefit – France, China, Russia, and even regional strongmen – will reinforce ties with Biya’s regime. This international environment, essentially permissive of authoritarian longevity in Cameroon, diminishes incentives for internal reform. It also means the opposition will find little external support beyond moral sympathy. Cameroon’s fate, therefore, rests largely in the hands of its own political actors and civil society, even as global powers quietly take their positions to engage with whichever way the wind blows in Yaoundé.

The 2025 presidential election in Cameroon has proven to be a pivotal event with far-reaching ramifications. Officially, it has extended President Paul Biya’s decades-long rule by seven more years, but the highly contested nature of the results has plunged the nation into a period of political tension and uncertainty. The immediate aftermath – characterized by opposition outcry, deadly street protests, and a forceful government clampdown – highlights the severe erosion of public trust in electoral processes and the lengths to which the regime will go to maintain its grip on power. In the short term, Cameroon faces a precarious balancing act: the government may have quelled the visible unrest for now, but underlying grievances regarding governance, economic marginalization, and ethnic exclusion remain unresolved and potentially combustible. National unity is under strain as key communities feel disenfranchised, whether it’s the Anglophone minority ravaged by conflict or opposition-aligned groups believing their electoral voice was silenced. The specter of ethnic polarization, if manipulated by cynical politics, could further weaken the social fabric.

Looking ahead, Cameroon stands at a crossroads between regime continuity and change. On one path, Biya’s continued rule – possibly leading into a managed dynastic succession – would signal a deepening of authoritarian governance. This could bring short-term stability of a sort, but at the cost of democratic legitimacy and potentially setting the stage for a messy succession crisis that could destabilize the country. The other path, far less certain, would involve opening up the political space through genuine dialogue and reform, addressing the roots of conflicts and discontent. That route would require unprecedented willingness by the ruling elite to compromise – something not evident thus far. With Biya showing no inclination to relinquish power and the opposition currently stymied, the likely scenario is a continued stalemate, where authoritarian consolidation meets simmering public frustration. Without inclusive dialogue and serious reforms, the country risks a future of continued unrest and possibly a crisis of succession that could unravel years of relative peace.

More on this story: Cameroonian rebel groups start rivalry for power and access to finances

More on this story: The Road to Yaoundé: Risks, Power, and Succession in Cameroon’s 2025 Vote”

More on this story: Escalating conflict in Cameroon: civil war looms in the region

More on this story: Reasons and scenarios of Ethno-Political Tensions in Cameroon