The Kremlin has begun aggressively defending the regime in Budapest ahead of the April 2026 elections. It is evident that Moscow aims to strengthen its influence in Hungary and destroy the opposition movement in the country by creating a replica of the Russian regime, with its corresponding level of freedom of speech, political rights, and civil liberties. Following a mafia-style logic, Moscow is pulling Orbán and his entourage into corrupt schemes that deepen his dependence on Russia and expand Hungary’s capacity for subversive activity inside the EU and NATO.

In an interview with The Financial Times, Péter Magyar, the leader of Hungary’s opposition Tisza Party, said that his party’s servers had been attacked by a cybercriminal group whose traces lead back to Russia. Magyar also drew attention to a recent statement by Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), which accused the EU, Ukraine, and his political movement of conspiring to overthrow Orbán. The politician called these accusations “blatant disinformation” and said they show that “Putin has begun interfering in the campaign.”

Context: In early November, the personal data of 200,000 Tisza supporters was leaked online. The information had been stolen from the party’s mobile application. Later, unknown actors uploaded the data, along with home addresses, to an interactive map.

The website hosting the map allows users to view supporters’ phone numbers, email addresses, and physical addresses with geographic coordinates. This creates opportunities for targeted harassment and intimidation of voters. In addition, Russia gains the possibility of offering Orbán its own bot farms as a tool against the Hungarian opposition.

According to a poll conducted at the end of October by the research company Závecz Research, support for the Tisza Party stood at 48 percent, compared to 37 percent for Orbán’s Fidesz.

According to Péter Magyar, “Viktor Orbán is Vladimir Putin’s closest ally in the EU.” For this reason, Magyar believes, the Russian president “is interested in ensuring that Orbán remains in power.”

The Russian cyber operation targeting Hungary’s Tisza Party represents a deliberate attempt by Moscow to weaken the only Hungarian political force capable of challenging Viktor Orbán’s pro-Kremlin course. The attack fits a long-standing SVR pattern: pre-election disruption, selective kompromat harvesting, and shaping the political environment in an EU/NATO state in Russia’s favour.

The operation is not isolated. It is part of a broader Russian strategy to keep Hungary aligned with Moscow, undermine EU unity, and prevent the emergence of a Hungarian government that would revert to Western strategic discipline.

The Tisza Party, with its growing public support and explicitly pro-European positioning, threatens the foundations of Russia’s influence in Budapest. For Moscow, Tisza represents:

- A threat to the Orbán–Kremlin partnership, which has been a key Russian wedge inside the EU and NATO.

- A potential shift in Hungary’s foreign policy toward alignment with Brussels, Washington, and Kyiv.

- A risk of Hungary abandoning Russia-friendly policies, including energy dependence, sanctions obstruction, and political cover for Moscow’s narratives.

Any electoral strengthening of Tisza is strategically damaging for Russia.

For these reasons, the party became a target of hostile Russian cyber activities in 2024–2025.

Why Russia Attacked the Tisza Party: Strategic Motives

2.1. Preserve Orbán as Moscow’s most valuable EU asset

Orbán provides the Kremlin with:

- a veto within EU institutions,

- a spoiler in NATO,

- a normalizer of relations between Moscow and Washington,

- an internal European amplifier for anti-Ukraine rhetoric.

A Tisza electoral rise threatens to dismantle this architecture.

For Moscow, the most efficient method to protect Orbán is to delegitimize, disrupt, and compromise his main challenger, especially one not yet hardened against foreign interference.

Pre-empt democratic change and weaken opposition infrastructure

SVR and FSB cyber units target parties that:

- are organizationally young,

- lack robust cyber-defense,

- rely heavily on digital mobilization.

Tisza fits all criteria.

By striking early, Russia aims to:

- steal internal communications,

- map donor networks,

- identify vulnerabilities,

- collect kompromat for selective leaks during campaign season.

This is the same blueprint Russia deployed in Montenegro (2016), Czech Republic (2018–2021), and Moldova (2023).

Control the information environment before the next Hungarian elections

Russian cyber operators typically attack 18–24 months before an electoral cycle, securing:

- psychological pressure on opposition leadership,

- internal confusion,

- resource exhaustion,

- opportunities to plant disinformation about internal conflicts.

Any leak—authentic or fabricated—could be used to portray Tisza as:

- corrupt,

- Western-controlled,

- divided,

- incompetent.

Narrative warfare is the end goal.

Protect Russian economic and intelligence assets in Hungary

Hungary hosts:

- Russian energy leverage (Rosatom, oil, gas contracts),

- banking networks,

- SVR/GRU cover structures,

- illicit logistics corridors between Russia and the EU.

A Tisza-led government would likely review or terminate:

- Paks-2 nuclear agreements,

- Russian banking licenses,

- covert diplomatic presences,

- intelligence hubs disguised as cultural or trade missions.

Moscow’s cyber move is defensive: protect operational infrastructure.

Punish Hungary’s “dangerous drift” toward internal opposition

In Russian doctrine, a mass mobilization behind an anti-government movement in an allied state is interpreted as a foreign-influenced regime change attempt.

Tisza’s rising popularity—especially its momentum among younger voters—triggered Russian alarm.

For the Kremlin, the party is seen as:

- a pro-EU force,

- a potentially hostile future government,

- a vector for Western influence inside Hungary.

This labels Tisza an adversary, justifying active cyber measures.

What Russia Aimed to Achieve (Operational Purposes)

3.1. Intelligence collection / kompromat harvesting

Primary operational goal: obtain internal documents, correspondence, donor lists, and any material that can be used later.

SVR has a long record of:

- exfiltrating internal opposition files,

- using doctored leaks to destroy reputations,

- providing data to friendly media outlets.

If kompromat cannot be found, fabrication is always an option.

Manipulate public trust in the party

Cyberattacks allow Russia to:

- portray the party as incompetent in protecting data,

- erode voter confidence,

- fuel conspiracy narratives about foreign funding or internal corruption,

- trigger internal paranoia.

Emotional destabilization is part of the operation.

3.3. Shape the pre-electoral narrative in Hungary

After breaching systems, Russia can:

- leak selectively during campaign season,

- distort materials,

- plant fabricated emails,

- time releases strategically before debates or elections.

The goal is not accuracy but atmospheric manipulation.

3.4. Pressure Orbán to harden his anti-opposition measures

Russia’s attack implicitly supports Orbán’s narrative that:

- the opposition is “vulnerable,”

- internal threats justify extraordinary control measures,

- foreign powers manipulate domestic politics.

Moscow understands its operations will reinforce the Hungarian government’s internal tightening, benefiting Russian interests.

SVR’s Role: Structure, Method, and Footprint

Why SVR, not GRU or FSB

The attack carries the hallmarks of SVR’s “Center 18” and affiliated cyber units:

- focus on political parties abroad,

- high operational discipline,

- quiet exfiltration rather than destructive attacks,

- long-term infiltration rather than short-term disruption.

GRU would have used noisier destructive malware.

FSB tends to operate in post-Soviet space, not inside the EU.

SVR is the Kremlin’s prime long-range intelligence service for political influence operations in the West.

Likely operational model

The operation appears structured around:

- Spear-phishing senior Tisza figures and organizers

- Credential harvesting from campaign tools

- Silent infiltration of communication platforms

- Lateral movement to donor databases

- Exfiltration of sensitive political communications

- Option for future leak operations

This follows the same sequence used in:

- the 2016 U.S. DNC breach,

- attacks on French En Marche (2017),

- hacks against German Bundestag groups (2015–2021).

SVR’s strategic tasking from Moscow

The Kremlin’s strategic instructions can be summarized as:

- protect Orbán,

- undermine Tisza,

- shape Hungarian politics to maintain pro-Russian neutrality,

- preserve the Hungarian veto inside EU and NATO,

- keep EU unity fractured.

The cyberattack is part of this structured plan.

Why Now? Timing Analysis

Tisza’s rapid rise scares Moscow

As the party gains legitimacy, Moscow sees a narrow window to intervene before it builds robust cyber defenses.

EU–Ukraine strategic decisions approaching

Hungary’s upcoming EU decisions—particularly on Ukraine—matter deeply for Russia.

Destabilizing Tisza ensures Orbán keeps total domestic control before these votes.

Russia fears losing one of its last strongholds inside the EU

Hungary is Russia’s most reliable wedge inside Europe.

Any political transition toward a centrist, pro-EU party is unacceptable for Moscow.

Consequences and Risks Going Forward

High-Probability Outcomes

- More aggressive Russian cyber activity during election season.

- Targeted kompromat leaks timed to weaken Tisza.

- Amplification of the attack by pro-government Hungarian media.

- SVR attempts to compromise Tisza’s international contacts.

Medium-Probability Outcomes

- Fabricated email leaks or manipulated documents.

- Russian IO campaigns portraying Tisza as Western agents.

- Backchannel pressure on Orbán to escalate internal controls.

Low-Probability but High-Impact Outcomes

- A destructive cyber component (wiping servers) if Orbán demands Russia’s help.

- “Hybrid” pressure using both cyber and influence operations simultaneously.

he Russian cyberattack on the Tisza Party is strategic, not tactical.

It serves a central Kremlin objective: preserve Orbán, maintain Hungary as Moscow’s gateway into EU and NATO policymaking, and pre-empt any political transition that might realign Budapest with Western strategic norms.

The SVR’s involvement confirms that Moscow now sees Tisza as a genuine strategic threat—a potential catalyst for dismantling one of Russia’s most valuable European footholds.

The attack is only the beginning of a broader Russian campaign that will intensify as Hungary approaches its next electoral cycle.

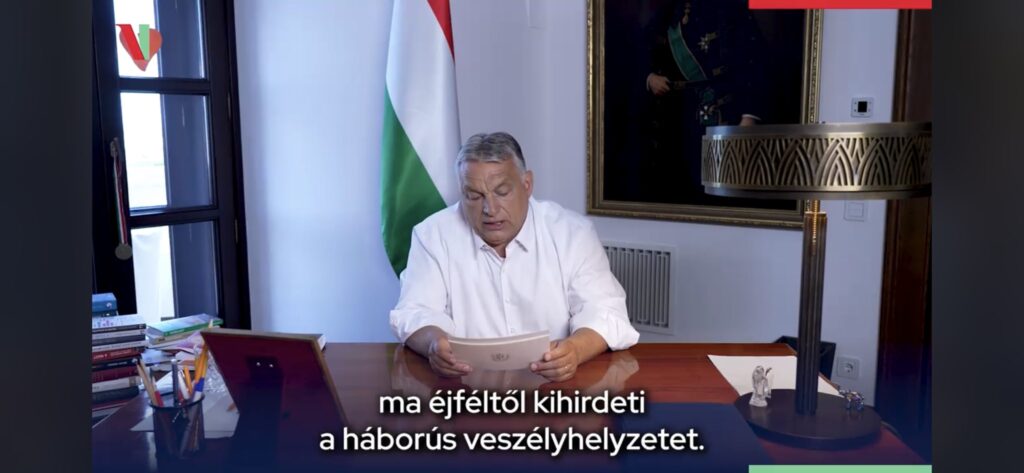

For more than 15 years in power, Orbán has built an autocracy in which democratic institutions formally exist, but government control over the media, the courts, and the electoral system ensures the dominance of Fidesz.

The opposition faces administrative pressure, censorship, and systematic discreditation. The cyberattack on the Tisza Party is not only an act of external interference but also a symptom of the internal vulnerability of Hungary’s democratic institutions.

• Viktor Orbán systematically clashes with European Union institutions, blocking key decisions. Brussels has attempted to influence Budapest through financial pressure — by freezing EU funds — but the effectiveness of this strategy is diminishing. Orbán uses Eurosceptic rhetoric to mobilize his electorate, presenting himself as the defender of “national sovereignty” against the “dictate of the EU.”

• Orbán remains the only EU leader who openly maintains ties with the Kremlin, even after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. He opposes sanctions, promotes energy deals with Moscow, and uses anti-Ukrainian rhetoric. This stance contradicts the EU’s position and undermines Western unity. At the same time, it demonstrates that Orbán views Russia as an alternative center of influence capable of guaranteeing his political survival.

• Orbán’s recent trip to the United States, which resulted in a temporary exemption from U.S. sanctions on the import of Russian oil and gas, provoked sharp criticism from the opposition. Péter Magyar described the visit as the prime minister’s personal rescue, not a diplomatic success for Budapest. Hungary remains deeply dependent on Russian energy resources, which limits its foreign-policy maneuverability and increases its vulnerability to Kremlin pressure.

• The rapid rise in support for the Tisza Party reflects Hungarian society’s fatigue with Orbán’s rule. Magyar and his party have a realistic chance of winning the upcoming parliamentary elections. This makes him a target for both internal attacks and external interference. His success could mean not just a change of government, but a transformation of Hungary’s policies toward the EU, Ukraine, and Russia.

• The parliamentary elections in Hungary may be decisive: for the first time in many years, the opposition has a real chance of victory. Fidesz fears losing power because this would trigger investigations into government corruption and a review of foreign policy. This is why the campaign is accompanied by aggressive rhetoric and attempts to discredit Orbán’s political opponents and Fidesz’s rivals.

• Russia has a strategic interest in keeping Orbán in office. Through Hungary, the Kremlin seeks to influence European policy, block EU decisions on Ukraine, and fracture the unity of the EU. The cyberattack on the opposition’s servers is part of a broader interference campaign aimed at preserving a government loyal to Moscow.

• If the opposition wins, Hungary may radically shift course and become an active ally of Ukraine within the EU.This would unlock stalled decisions in Brussels, strengthen sanctions against Russia, and reinforce the eastern flank of Europe. Such a scenario is dangerous for Moscow. That is why the Kremlin is trying to discredit the Hungarian opposition.

• The attack on the Tisza Party servers is not an isolated incident but a manifestation of hybrid warfare, in which Russia interferes in other countries’ democratic processes. It mirrors previous interference campaigns targeting elections in the United States, France, and Germany. Such actions are intended not only to intimidate opposition supporters, but also to undermine public trust in democratic institutions.

Theses That Could Shift Washington’s Position Toward Orbán

How the Russian cyberattack on Tisza becomes a U.S. policy lever

Orbán is enabling Russian penetration of a NATO ally

Thesis: The Tisza cyberattack demonstrates that Moscow believes Hungarian political space is permissive and penetrable — a direct result of Orbán’s long-term alignment with Russian intelligence structures.

Impact on Washington:

Positions Orbán not as a “difficult ally” but as a vector of Russian influence inside NATO, triggering bipartisan pressure for corrective action.

Hungary is becoming Moscow’s operational safe zone inside the EU

The attack reveals that Russian cyber operators feel secure operating through Hungary, treating the country as a friendly operational environment.

Strengthens calls in Washington to treat Hungary as a counterintelligence vulnerability, not a partner.

This can fuel measures such as:

- restricted intel sharing,

- downgraded NATO access,

- tighter screening of Hungarian diplomats.

Russian interference targets Hungarian democratic opposition — an attack on Western democratic norms

Thesis: Cyber operations against Tisza mirror the Kremlin’s tactics against U.S., French, German, and Czech parties.

Impact:

Washington frames the incident as part of a pattern of attacks on democracy, which undermines Orbán’s narrative that Hungary is “neutral” or sovereign.

Expect pressure from:

- Senate Foreign Relations Committee,

- Helsinki Commission,

- State Department DRL.

4. Orbán is no longer an “illiberal but stable partner” — he is now a facilitator of Russian destabilization

Thesis: Moscow attacked the opposition because it trusts Orbán to shield Russian political and intelligence interests in Hungary.

Impact:

Reframes Orbán from “autocratic but predictable” to strategically compromised.

This unlocks appetite in Washington for punitive steps.

5. Hungary’s position threatens the cohesion of NATO’s eastern flank

Russian interference in Hungary’s internal politics shows Moscow’s confidence in controlling Budapest’s posture on:

- Ukraine,

- sanctions,

- NATO decisions.

Makes Orbán appear as a strategic liability during the most dangerous period in European security since the Cold War.

This is powerful inside Pentagon and NATO channels.

Orbán’s protection of Russian networks endangers U.S. assets in Europe

The cyberattack indicates Russia’s intelligence presence in Hungary is deep, active, and politically shielded.

Washington may conclude that U.S. diplomatic, military, and intelligence assets in Hungary are exposed — prompting:

- stronger security protocols,

- pressure on Budapest to expel Russian operatives,

- potential U.S. sanctions targeting Kremlin-linked networks in Hungary.

Orbán’s alignment with Russia undermines U.S. global messaging on defending democracies

: The Kremlin used Hungary as a battleground because Orbán has weakened democratic institutions and opposition protection.

Creates heavy pressure on the U.S. administration from Democrats and moderate Republicans to distance Washington from Budapest, arguing that U.S. credibility is at stake globally.

The attack proves Hungary cannot be trusted on EU or NATO decisions involving Russia

Thesis: If Russia interferes domestically and Hungary responds weakly, Budapest cannot be relied on in:

- sanctions decisions,

- Ukraine support,

- NATO defense planning.

Impact:

Pushes Washington to advocate inside NATO for procedural reforms to limit the impact of a single pro-Russian government.

Orbán looks increasingly like Russia’s political firewall inside Europe

The fact that Russia struck only the opposition — not the Hungarian government — exposes the mutually beneficial relationship.

Strengthens the argument in Washington that Orbán is a strategic asset for the Kremlin, not a neutral actor.

U.S. credibility suffers if it ignores Russian interference in a NATO state

\ Washington’s silence would signal permissiveness toward Russian political warfare inside the Alliance.

Drives the administration toward a firmer posture, at minimum:

- public criticism,

- conditionality on bilateral cooperation,

- intelligence briefings to Congress highlighting Orbán’s vulnerability to Moscow.

Overall Assessment: Which theses matter most in Washington?

Most influential to U.S. policymakers:

- Orbán as a Russian-enabling actor inside NATO

- Hungary as a compromised intelligence environment

- Democratic interference narrative (Tisza attack = Russia vs democracy)

- Risk to NATO cohesion and U.S. credibility

These four arguments are powerful enough to shift Washington’s stance toward tangible measures — including restrictions, public rebukes, or coordinated pressure with Brussels.

More on this story: Civic Resistance Grows Against Orbán’s Authoritarian Drift”

More on this story: Hungary’s Balancing Act: Strategic Risks of Budapest’s Covert Ties with Russia

More on this story: Hungary plays as China’s bat to kick the US out of the EU economy

More on this story: Hungary: Trojan Horse in Russia’s Proxy War Against Europe

More on this story: From Transcarpathia to the Kremlin: Budapest’s Quiet War

More on this story: Peacekeeper or Invader? Hungarian Forces and the Future of Western Ukraine

More on this story: Hungary’s Espionage Against EU Institutions: