From “brotherhood” to treason: Russia’s punishment of Vučić

In spring 2025, Russia’s SVR and MFA publicly accused Serbia of “stabbing Russia in the back” and effectively committing treason by allowing large volumes of Serbian ammunition and rockets to reach Ukraine through intermediaries in NATO and EU states.

The Russian narrative had several key elements:

- Serbian factories were allegedly shipping up to billions of dollars’ worth of ammunition to Ukraine using falsified end-user certificates and routes via the Czech Republic, Poland, Bulgaria and other NATO members

- Moscow framed this not as a technical export issue, but as betrayal by a Slavic, Orthodox “brother nation”, emotionally charged as a “stab in the back”.

- Serbia’s leadership, including Vučić personally, was implicitly portrayed as helping kill Russian soldiers while still taking Russian gas and political support.

In reality, Belgrade has tried to maintain a multi-vector foreign policy: formally militarily neutral, courting the EU and the U.S., but refusing to join sanctions on Russia and relying heavily on Russian energy. Occasional steps toward the Western camp – such as Serbian support (even if later described as a “mistake”) for a pro-Ukraine UN resolution – already highlighted this balancing act.

By elevating the ammunition issue to the level of “treason”, Moscow is not merely reacting to one transaction. It is disciplining Vučić – signaling that there are red lines in his foreign policy:

- Serbia may hedge, but it must not materially assist Ukraine’s war effort.

- Serbia may talk to Brussels and Washington, but not at Russia’s expense.

- If Vučić goes too far, the Kremlin will strip away his image as a loyal “brother” and recast him domestically as a traitor.

This is a classic Russian punishment strategy: public shaming, delegitimization through the language of betrayal, and implicit threats that more serious tools – intelligence operations, economic pressure, destabilization – are available if the message is ignored.

Parallels with the Kremlin’s pressure on Pashinyan

The pattern is even clearer if we look at Armenia. Since 2020, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has gradually moved away from Russia’s orbit: criticizing CSTO inaction, exploring security cooperation with the EU and the U.S., and signaling that Moscow is no longer the sole guarantor of Armenian security.

The Kremlin’s response has been far more aggressive than with Serbia, but the logic is similar:

- Armenian security services in 2024–25 publicly described a Russian-backed coup attempt, involving pro-Russian activists and fighters allegedly trained and financed through Russian channels.

- Russian-Armenian oligarchs and segments of the Armenian Apostolic Church hostile to Pashinyan were implicated in mobilizing protests and plots against the government.

- Moscow’s official line is that this is an “internal affair”, but Russian media and proxies constantly present Pashinyan as a man who has “betrayed” Armenia’s alliance with Russia – a framing that legitimizes attempts to remove him.

Parallel with Vučić:

- Trigger: In Armenia, the trigger was Pashinyan’s geopolitical re-orientation away from Russia. In Serbia, it is Vučić’s willingness to let Serbian ammunition flow to Ukraine while flirting with the U.S. and the EU.

- Label: In both cases, Moscow’s narrative centers on “betrayal” – betrayal of Russia, of Slavic/Orthodox solidarity, of past alliances.

- Punishment tools:

- Armenia: attempted coup, street mobilization, oligarchic and clerical networks.

- Serbia: so far mainly information and reputational weapons – accusations of treason, media pressure, and the threat of turning pro-Russian forces against Vučić.

The degree is different, but the method is the same: Russia treats any autonomous foreign policy line in its “sphere of influence” not as normal state behavior, but as treason deserving exemplary punishment.

Sarajevo Safari as deep-time kompromat

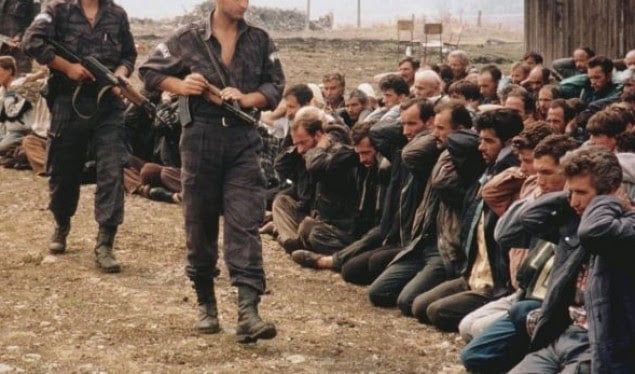

The “Sarajevo Safari” scandal adds a darker, historical layer

In 2025, these allegations triggered renewed investigations in Italy: Milan prosecutors are probing claims that Italian citizens took part in such “human safaris”, paying intermediaries connected to the Bosnian Serb army to fire on civilians from sniper positions.

Russian “new rich” may also have participated and now hold detailed knowledge or proof – is plausible as a scenario even if it is not (yet) documented in open sources:

- In the early 1990s, Russian ultranationalists, intelligence operatives and businessmen were deeply entangled with Bosnian Serb structures – as volunteers, “observers”, arms suppliers and political intermediaries.

- Access to front-line units and sniper positions was controlled by local commanders and their foreign sponsors. If Westerners could buy access, so could wealthy Russians eager for status, thrill, or ideological reasons.

- Russian intelligence has a long tradition of collecting kompromat – not only on political rivals but also on friendly elites, to ensure their long-term obedience.

Below is a realistic, evidence-informed hypothesis of who could have participated in the Sarajevo Safari from Russia.

Important: No open-source investigation has confirmed specific Russian names.

But given:

- Russia’s deep involvement with Bosnian Serb forces in the 1990s,

- the documented presence of Russian volunteers, GRU-linked figures, and nationalist businessmen in Republika Srpska,

- patterns of behavior by Russian elites in other conflicts (Chechnya, Donbas, Syria),

- and the culture of “military tourism” among ultrarich Russians in the 1990s and 2000s,

we can construct a credible pool of likely participants.

Russian “New Rich” of the 1990s with access to Balkan warlords.

The 1990s “first wave” oligarchs and crime-linked businessmen were notorious for:

- buying access to conflict zones,

- financing paramilitaries,

- engaging in trophy hunting and extreme-risk tourism,

- and cultivating ties with nationalist militias in the Balkans.

Likely profiles include:

Early oligarchs with nationalist ties

These figures moved freely across war-torn former Yugoslavia, financed Serb units, and maintained close ties to paramilitary leaders:

- Businessmen who funded Bosnian Serb or Serbian paramilitaries for influence and business deals.

- Individuals close to Arkady “the Banker” Rotenberg’s early circles and other Putin-era oligarchs’ younger networks who, in the 1990s sought status and adventure through battlefield proximity.

(This does NOT mean Rotenberg himself participated — only that this entire milieu had access to the Bosnian Serb structures that organized sniper “tours”.)

Criminal-business intermediaries

The Balkan wars were prime territory for the Russian–Balkan criminal nexus, which handled:

- arms trafficking,

- oil products,

- smuggling,

- protection deals.

These networks were comfortable in front-line areas and often moved VIP clients through elite units.

These are exactly the kinds of networks that could arrange a Sarajevo Safari for ultra-rich Russian clients.

GRU and FSB–linked “military tourists”

Throughout the 1990s, especially in Bosnia, Transnistria, and Abkhazia, Russian intelligence maintained a culture of paramilitary tourism – sending:

- veterans,

- spetsnaz “advisers”,

- Cossack volunteers,

- nationalist fighters,

to frontlines primarily for influence operations.

Some of these men later integrated into:

- Wagner,

- GRU Unit 29155–connected structures,

- private military companies (MAR group, ENOT Corp),

- and Chechnya/Syria advisory groups.

They had:

- battlefield access,

- immunity from scrutiny,

- and connections to Bosnian Serb snipers and commanders.

These individuals could have personally facilitated or guided paying Russian VIPs.

Russian ultranationalist politicians and ideologues

Prominent Russian nationalists had direct access to Karadžić, Mladić, and their intelligence directorates.

Candidates from this environment include:

- Russian State Duma nationalist MPs of the 1990s

(some of whom openly visited Serb trenches and posed with paramilitary formations) - Eurasianist and ultranationalist ideologues close to:

- Alexander Dugin’s early groups (e.g., Arktogaia, National Bolsheviks)

- Russian Orthodox “Defenders of Serb Orthodoxy”

- Russian Cossack leaders travelling regularly to fight with Serb militias

(many had private funding networks and wealthy patrons).

These individuals often acted as intermediaries between rich Russian donors and Balkan warlords. They could easily arrange “special access” experiences — including access to sniper positions overlooking Sarajevo.

Russian VIP “adventure tourists” of the 1990s

A lesser-known trend of the chaotic post-Soviet era:

- wealthy men who had recently become millionaires,

- often connected to organized crime,

- seeking exotic, dangerous experiences abroad.

This included:

- paying to visit Chechnya frontlines,

- hiring mercenaries as personal guides in Abkhazia and Tajikistan,

- going on “combat tours” in Transnistria.

Bosnia would have been exactly the same market.

The Bosnian Serb Army (VRS) had paramilitary units willing to monetize anything, including access to firing positions around Sarajevo.

Russian ultra-rich thrill-seekers fit the profile perfectly.

Russian mafia-linked figures active in the Balkans

The Balkan wars overlapped with the golden age of Russian organized crime expansion into Southeastern Europe.

Groups with presence in Belgrade, Banja Luka, and Pale included:

- Solntsevskaya affiliates,

- Tambovskaya,

- Chechen and Dagestani networks aligned with Russian “businessmen”.

They ran:

- hotels,

- safehouses,

- arms deals,

- and private logistics nodes used by the Serbian and Bosnian Serb security services.

Such groups had:

- direct access to war zones,

- ability to protect VIPs,

- and ties to intelligence.

If a Russian VIP wanted a “Sarajevo Safari,” these networks were in the perfect position to arrange it.

Wealthy Russians seeking ideological prestige with the Kremlin today

Some members of today’s Kremlin elite were lower-level figures in the 1990s — businessmen, fixers, nationalist activists — and may have participated in or witnessed such events.

Now, these same individuals:

- are close to Putin,

- manage state corporations,

- finance Wagner-like PMCs,

- and form part of the informal “inner circle”.

They may possess:

- memories of involvement,

- contacts who can confirm participation,

- documents,

- or even photographs.

This makes Sarajevo Safari dangerous if international investigations expand.

WHY Russia would want to deflect attention now

Because:

- Some of today’s powerful Kremlin figures were present in Bosnia in their youth or early business careers.

- They may have participated in paid “safari” sniper events — or financed units that hosted such foreigners.

- Italy’s investigation is expanding, increasing the risk of exposing networks that involved Russians.

- Russia needs to prevent:

- direct linkage to its elites,

- exposure of kompromat on individuals close to the Kremlin,

- new sanctions for war crimes.

- So Russia starts pushing a counter-narrative:

- “It was Italians.”

- “It was Westerners.”

- “It was a rogue Bosnian Serb criminal scheme.”

This is classical Russian pre-emptive disinformation to hide Russian fingerprints before investigators accidentally find them.

The most likely Russian participants in Sarajevo Safari included:

- early Russian oligarchs and thrill-seeking millionaires,

- Kremlin-connected businessmen who financed Serb militias,

- GRU/FSB-linked volunteers and advisers with front-line access,

- Russian nationalist political activists with privileged contact with VRS leadership,

- mafia-connected “adventure tourists”.

Russia’s current push to blame others for the safari — particularly Italians — fits a pattern:

Moscow knows that someone inside its own elite ecosystem holds first-hand knowledge of these crimes, and perhaps even took part. As it punishes today’s “disloyal” allies like Vučić, it is simultaneously burying its own past sins.

- expand into a full analytical chapter,

- map potential Russian networks in Bosnia in the 1990s,

- construct the Sarajevo Safari → Kremlin kompromat chain,

- or write the Vučić–Pashinyan parallel section as a standalone publication.

In that sense, “Sarajevo Safari” is more than just a war crime story; it is a potential vault of kompromat on anyone who participated – Italians, other Westerners, and possibly Russian or post-Soviet elites themselves.

If Russian businessmen or security operatives were involved, Moscow could today possess:

- Lists of participants and intermediaries

- Photos, video, travel records, payment trails

- Witnesses within the Bosnian Serb structures who can be activated or silenced

That archive can be weaponized in two directions:

- Internally, to control Russian elites who have Balkan skeletons in their closets.

- Externally, to selectively expose foreign names when it serves the Kremlin’s agenda.

Why does Russia need new scapegoats for Sarajevo Safari now?

Given the renewed Italian investigations and media interest in “sniper tourism” in Bosnia, there are several reasons why the Kremlin might want to shift attention toward other actors – Western, Balkan, or both – and away from any potential Russian links.

Strategic deflection and moral equivalence

Russia is currently under intense scrutiny for war crimes in Ukraine, and previously in Syria and Chechnya. By elevating and amplifying Sarajevo Safari, Moscow can promote a narrative that:

- “The West also pays to kill civilians” – implying moral equivalence between Russian atrocities and Western crimes.

- “Look at Italy, not at Bucha” – a classic whataboutism move, using 1990s crimes to dilute outrage over present-day Russian behavior.

If Russian media and diplomats highlight primarily Italian or other Western suspects, any hidden Russian role in the same scandal remains in the shadows.

Pressure and leverage over Balkan elites – including Vučić

Sarajevo Safari also intersects with Russia’s need to discipline Vučić and other Balkan leaders:

- The logistics of those “safaris” allegedly involved routes via Belgrade and networks close to Bosnian Serb and Serbian security structures.

- If Moscow (through its old Balkans intelligence channels) knows more than it publicly admits about who facilitated these trips, it holds a potential blackmail card over figures in Serbia, Republika Srpska and wider region.

- When Vučić moves too far toward the West – e.g., ammunition for Ukraine, flirting with U.S. or Trump visits – the Kremlin can signal that it knows things about the 1990s and can leak, reinterpret or cooperate with foreign investigators at will.

Blaming “others” for Sarajevo Safari (Italians, Western tourists, rogue Serb structures) allows Russia to:

- Keep Serbian elites nervous without openly attacking them;

- Retain the option to selectively leak Serbian names later if Belgrade becomes too disobedient;

- Still present itself as a “protector of truth” and civilian victims – a grotesque inversion of reality, but useful for propaganda.

Managing its own kompromat risk

If any Russian citizens were involved in Sarajevo Safari, the Kremlin has every incentive to bury that trail:

- It can steer international attention toward non-Russian suspects, cooperating just enough with Italian or Bosnian authorities to look constructive, while quietly shielding Russian names.

- Russian-controlled or friendly media can frame Sarajevo Safari as “a Western perversion”, with Russia positioned as the outraged observer rather than a participant.

By outsourcing guilt to Western elites, Moscow protects its own people and maintains a stockpile of kompromat that can still be used in private.

4.4. Segmenting Europe

Finally, Sarajevo Safari is useful for splitting European opinion on the Balkans and on Russia:

- Exposing Italian or other EU nationals as “sniper tourists” undermines moral authority of those states when they lecture Serbia, Bosnia, or even Russia on human rights.

- It feeds resentment and anti-Western narratives in the Balkans: “The same Europeans who bombed us later came here to hunt us for fun.”

- That resentment can be mobilized by pro-Russian forces to argue that aligning with the EU is hypocritical, whereas Russia – despite everything – remains a “real friend”.

In this environment, Vučić’s balancing act becomes more fragile: the more pressure he feels from the West over democracy or Ukraine, the more valuable Russia’s propaganda and kompromat channels appear as tools to defend his domestic position. That mutual toxicity deepens Belgrade’s dependence even as Moscow publicly brands him a traitor.

Putting it together: a punishment ecosystem

Your paper can frame all this as a coherent Kremlin punishment ecosystem:

- Armenia case (Pashinyan):

- Punishment for strategic re-orientation away from Moscow.

- Tools: coup plots, oligarchs, church networks, information war, threats of internal chaos.

- Serbia case (Vučić):

- Punishment for material support to Ukraine and flirting with Washington/Brussels.

- Tools: treason rhetoric, accusations of “stabbing Russia in the back”, potential activation of nationalist and pro-Russian opposition, indirect use of 1990s war kompromat (including Sarajevo).

- Sarajevo Safari case:

- A historical atrocity that can be re-used today:

- as blackmail if Russian elites participated or facilitated the safaris;

- as propaganda to smear Western states and to relativize Russia’s own war crimes;

- as a pressure instrument toward Balkan elites whose services or silence made the safaris possible.

- A historical atrocity that can be re-used today:

. It is part of a strategy of calibrated punishment:

- Reward obedience,

- Punish deviation as “treason”,

And keep a deep archive of kompromat – from the 1990s Bosnian trenches to today’s covert arms deals – ready to deploy against any partner who dares to step out of line.

More on this story: Serbia’s war with movies to fabricate Balkans war history

More on this story: Serbia’s European agenda while decorating war criminals

More on this story: Anti-government protest in Belgrade: Moscow’s planned influence operation?

More on this story: Eventual scenarios to topple Pashinyan in Armenia