Why Cuba Comes Into Focus After Caracas

The U.S. capture of Nicolás Maduro and the de-facto decapitation of his regime in Caracas has blown a huge hole in Cuba’s survival ecosystem. Venezuela supplied around a third of Cuba’s oil in exchange for Cuban medical personnel and security advisers. Now that lifeline is under direct American control and subject to Washington’s decisions on sanctions and export licenses.

At the same time:

Cuba is in deep economic crisis (inflation, shortages, rolling blackouts).

The regime is politically weakened by the memory of the July 11, 2021 protests and subsequent mass repression.

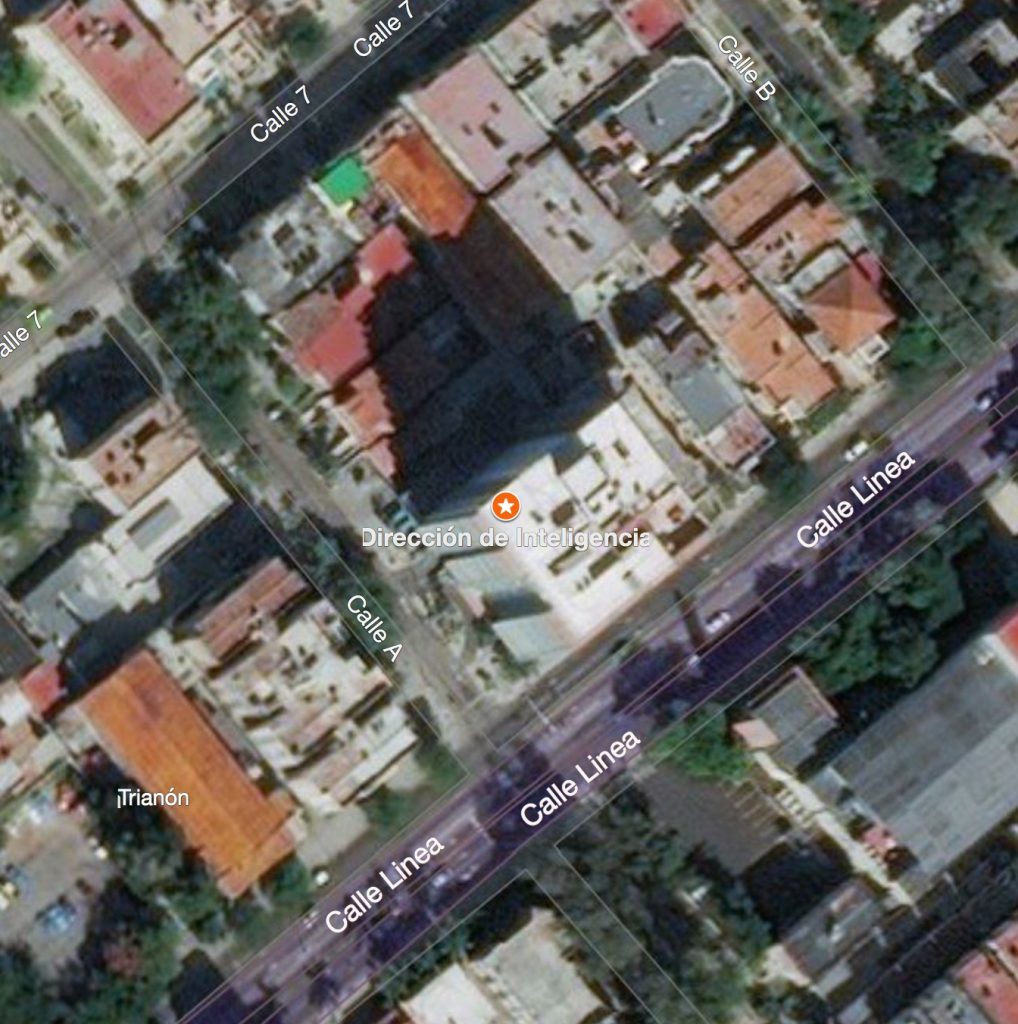

Cuba is hosting or facilitating Chinese and Russian intelligence facilities (radar, SIGINT, naval visits) close to U.S. shores and Guantánamo.

After the successful operation in Caracas, President Trump has already signaled that Cuba may be “the next focus” of U.S. attention, implying a broader Latin American strategy rather than an isolated Venezuelan episode.

Who in Washington Backs a Strategy to Dismantle Cuban Authority—and Why

Core political coalition

Cuban-American hardliners in Congress (Rubio, Díaz-Balart, others)

Longstanding objective of dismantling the communist regime, rooted in exile politics and family histories.

They argue that Cuba is:

- A state sponsor of anti-U.S. terrorism and refuge for American fugitives .

- A strategic platform for hostile powers (Russia, China) on U.S. doorstep.

- The Caracas operation is seen as precedent: if the U.S. “fixed” Venezuela, it can now “finish the job” in Havana.

- Trump White House and MAGA-aligned national security circle

- Ideological: collapsing “socialist dictatorships” in the Western Hemisphere is framed as proof of American strength and Trump’s “doctrine” of rollback.

- Domestic: Florida electoral politics—delivering symbolic victories against Havana and Caracas mobilizes Cuban-American and Venezuelan-American voters.

- Strategic: they portray Cuba as the central hub for narco-networks, intelligence threats (“Havana syndrome”), and as the brain behind Venezuela’s repressive apparatus.

Portion of mainstream Republicans and some Democrats focused on human rights

They are less interested in regime change rhetoric but strongly back tightening sanctions and accountability for the regime’s crackdown on protesters and political prisoners.

They supported targeted sanctions on Díaz-Canel and senior security officials for 11J-related abuses; in this scenario, these measures have already been renewed and expanded.

U.S. security and intelligence hawks

Alarmed by Chinese SIGINT facilities and new radar installations that can monitor Guantánamo and U.S. military movements. Concerned by renewed Russian naval and intelligence presence in Cuba and across the Caribbean.

Publicly Declared Justifications for a Hard Line on Cuba

Washington will package any post-Caracas strategy in a narrative that emphasizes legality, human rights, and security. Key public reasons include:

Human rights and political prisoners

- The U.S. will foreground Havana’s systematic repression after the 2021 protests—arbitrary detentions, harsh sentences, and ill-treatment of detainees documented by NGOs and the State Department.

- Sanctions on Díaz-Canel and his security chiefs are framed as personal accountability for these abuses.

Democratic aspirations of the Cuban people

- References to July 11, 2021 and subsequent smaller protests as evidence that Cubans want “freedom from dictatorship.”

- Washington presents itself as responding to a domestic Cuban demand, not imposing regime change from outside.

Regional security and great-power competition

- Chinese and (to a lesser extent) Russian intelligence infrastructure in Cuba, including new radar sites and SIGINT stations, is depicted as intolerable espionage platforms focused on U.S. forces, space launches, and communications.

- Post-Caracas, the argument is that leaving Cuba untouched would allow China and Russia to rebuild influence from Havana even as Venezuela falls under U.S. leverage.

Support for terrorism and fugitives

- Existing legislation demanding Cuba extradite American fugitives and alleged terrorists will be cited as evidence the regime “harbors criminals”, justifying further pressure.

Economic mismanagement and humanitarian crisis

- The regime’s mishandling of the economy, shortages, and blackouts are portrayed as proof that socialism has failed—and that the only sustainable path is political and economic opening.

Likely Operational Shape of a U.S. Strategy

Short of direct invasion, a realistic “dismantling” strategy would combine:

Energy and financial strangulation via control over Venezuelan oil

- With Caracas under U.S. control, Washington can throttle or condition oil flows to Cuba, transforming an existing vulnerability into a strategic lever.

Escalating but “legalistic” sanctions

- Tightening the embargo, adding more entities to the restricted list, and expanding targeted sanctions on Cuban military-run conglomerates.

Information operations and support to opposition & diaspora media

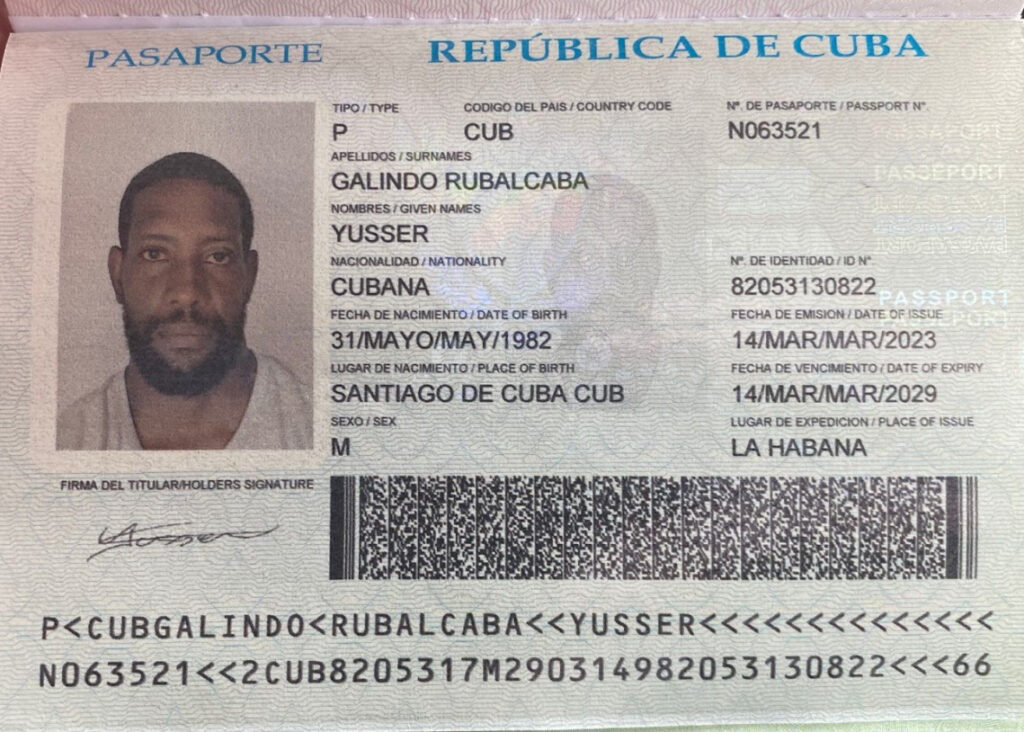

- Highlighting human rights abuses, corruption among party/military elites, and the lavish lifestyles of top officials, to widen the gap between population and regime.

- Leveraging diaspora media in Miami and digital tools to reach Cuban audiences, building on what Havana already claims was U.S. influence behind the 2021 protests.

Diplomatic isolation and multilateral pressure

- Pushing for resolutions in the OAS and within key Latin American forums condemning repression and Chinese/Russian bases on the island.

- Linking Cuba’s treatment of protesters and political prisoners to its access to international finance and development aid.

Covert and deniable activities

- Support to civil society, dissident networks, and possibly elements within the security apparatus that might favor a “controlled transition.”

- This would be publicly denied and framed as democracy assistance.

International Reaction

Latin America and the Caribbean

- Left-leaning governments (Mexico, Bolivia, parts of the Caribbean) will denounce a perceived “second regime-change operation” after Caracas, frame it as neo-imperialism, and rally rhetorical and diplomatic support for Havana.

- Centrist and right-of-center governments will be more cautious:

- They may privately welcome the end of Cuban interference and intelligence activities, but publicly condemn violations of sovereignty to avoid domestic backlash.

- CARICOM states dependent on Cuban medical brigades and energy deals will warn against sudden collapse in Cuba that could trigger regional health and migration crises.

Europe

- The EU will likely oppose any military scenario and stress international law, but some member states will quietly support stronger human-rights conditionality on Havana.

- Brussels will try to position itself as a mediator, advocating gradual political opening rather than forced regime collapse.

Russia and China

- China will condemn U.S. “hegemonic interference,” defend its “legitimate cooperation” with Cuba, and may try to harden or disperse its intelligence infrastructure on the island, or shift some capacity to other regional partners.

- Russia will use the crisis for information warfare—portraying the U.S. as destabilizing the hemisphere—while exploring whether it can still leverage naval visits or SIGINT cooperation in Cuba as bargaining chips vis-à-vis Washington.

Multilateral bodies

- The UN General Assembly will almost unanimously vote against the embargo and condemn coercive measures, as it has done for years, but resolutions will be non-binding.

- Human-rights mechanisms (UN, OAS, regional courts) may welcome targeted sanctions and call for prisoner releases but will warn against humanitarian consequences of blanket economic strangulation.

Implications and Scenarios

Inside Cuba

Regime hardening vs. controlled transition

- Short term: the leadership will rally around Díaz-Canel, frame the Caracas operation as “state terrorism” and accuse the U.S. of preparing similar actions against Cuba.

- Medium term: a shrinking oil supply and tighter sanctions could deepen elite fissures between ideological hardliners and technocrats who quietly favor negotiation.

Risk of social explosion and migration wave

- Economic collapse plus political pressure makes another 11J-type explosion probable—but with less fear and more desperation.

- Havana may respond by opening migration valves toward the U.S., weaponizing irregular migration in the Florida Straits.

Probability of an anti-U.S. insurgency

- A sustained armed insurgency against U.S. forces remains unlikely unless Washington pursues overt military action or prolonged occupation.

- If the U.S. limits itself to indirect pressure and covert support, violent resistance will mostly target the regime, not Americans—though attacks on U.S. interests and Cuban-American targets cannot be excluded.

For the Region and Global Politics

Precedent of consecutive regime-change campaigns

- Caracas + heavy pressure on Havana will be read globally as a revival of 20th-century U.S. interventionism, complicating U.S. narratives on Ukraine, democracy promotion, and respect for sovereignty.

- Russia and China will exploit this to discredit U.S. positions in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

Strategic repositioning of great powers in the Caribbean

- If Cuban authority truly fragments, China and Russia may seek fallback positions in Nicaragua, smaller Caribbean islands, or even friendly South American ports, dispersing rather than eliminating their footprint.

- Domestic U.S. politics

- A perceived “dual victory” over Maduro and the Cuban regime would be a powerful symbol for Trump and his allies.

- But any humanitarian crisis or chaotic transition in Cuba—especially mass migration—could boomerang politically, being framed as a self-inflicted disaster.

After the Caracas operation, Washington’s most realistic strategy toward Cuba is intensified, multi-dimensional pressure aimed at internal collapse or negotiated transition, not a copy-paste of the Venezuelan military raid. The political center of gravity in Washington—Cuban-American hardliners, the Trump White House, security hawks, and human-rights advocates—converges around the idea that the current Cuban authority is illegitimate, dangerous, and unsustainable.

Whether this strategy succeeds, however, will depend less on speeches in Washington and more on three uncertain variables: elite fractures in Havana, the Cuban population’s tolerance for further hardship, and how far China and Russia are willing to go to preserve their outpost 150 kilometers from Florida.

From a Bay of Pigs perspective, the Caracas-style operation against Cuba carries three big families of risk for the U.S.: military/operational, political-strategic, and alliance/legitimacy. Bay of Pigs is the perfect warning case: a small, deniable intervention that was supposed to trigger an uprising, instead turned into a humiliation that strengthened the very regime it targeted.

I’ll frame the risks as “Bay of Pigs ghosts” that could repeat.

Military and Operational Risks

Over-reliance on an expected uprising

Bay of Pigs lesson: planners assumed the Cuban population and parts of the army would rise once exiles landed; no such uprising happened and the invaders were quickly isolated and defeated.

Today’s risk:

If Washington designs pressure or covert action on Cuba assuming:

- rapid mass protests;

- security-service splits;

- “Brigade 2506 2.0” from Miami inspiring the island—

it may again misread fear, repression capacity and nationalism. A failed gamble could:

allow Havana to crush internal opponents;

discredit pro-U.S. groups as “foreign agents”;

prove the regime’s narrative that “the Revolution defeated the Yankees again.”

Underestimating regime capabilities and reaction speed

Bay of Pigs: Castro rapidly mobilized 20–25,000 troops; air strikes were insufficient; the tiny exile force was overwhelmed in 72 hours.

Today: Cuban intelligence and counterintelligence are far more experienced, with deep penetration of dissident circles and diaspora networks. Any covert plan risks:

early compromise and pre-emptive arrests;

staged “false opposition” groups feeding disinformation back to U.S. planners;

rapid military counter-moves that turn a small U.S. or proxy operation into a televised rout.

Limited escalation control

Bay of Pigs: Kennedy tried to keep the operation “plausibly deniable”, restricted air cover and conventional U.S. forces, which guaranteed failure once things went wrong.

Caracas–Havana scenario:

If Trump again insists on deniability and tight ROE to avoid open war, U.S. commanders may be unable to rescue a faltering operation.

If he does escalate (air strikes, naval blockade, direct landings) to avoid another Bay of Pigs humiliation, the conflict risks widening—especially if Chinese or Russian assets or personnel are hit.

So Washington risks being trapped between another “perfect failure” and an open regional war.

Political and Strategic Risks

A new “Bay of Pigs stigma” on the presidency

Historically: Bay of Pigs badly damaged Kennedy’s reputation, triggered internal investigations and intense criticism of his judgment and the CIA.

Now: if the operation to dismantle Cuban authority stalls or backfires:

- Trump personally carries the blame for “Bay of Pigs 2.0”;

- Congress will investigate intelligence failures, internal dissent, and possible manipulation by exile lobbies;

- his broader Latin America strategy is discredited, complicating any further coercive diplomacy.

Even a tactically mixed result (e.g., partial success but heavy casualties or chaos) could politically look like a fiasco.

Strengthening the Cuban regime and anti-U.S. nationalism

Bay of Pigs allowed Castro to:

- purge moderates;

- militarize society;

- request Soviet missiles, which led to the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

In a new crisis:

- Díaz-Canel & co. would use the operation to enforce total wartime discipline, decapitate any “soft” elements in the system, and militarize the economy even further;

- they could invite more Chinese and Russian military/intelligence presence, not less, as a security guarantee.

Result: opposite of U.S. intent – a more radical, securitized, foreign-backed regime.

Blowback in the intelligence and military system

Bay of Pigs produced:

- serious critiques of CIA leadership, internal IG reports listing analytic, planning and coordination failures;

- long-term tension between the White House and the Agency.

A failed or messy Cuban operation today could:

- reignite debates about politicized intelligence, exile influence, and “mission creep” from covert action to quasi-war;

- deepen mistrust between the presidency, Pentagon and CIA if each blames the other for the outcome.

Alliance, Legal and Image Risks

Loss of moral high ground and accusations of hypocrisy

In 1961–62, many countries saw Bay of Pigs and later Operation Mongoose as classic Cold War interventionism.

In today’s context—where Washington asks others to respect Ukraine’s sovereignty and condemn Russian invasions—another U.S.-driven overthrow attempt in Cuba would:

give Russia and China a propaganda gift: “The U.S. does in its backyard what it denounces in ours.”

undermine U.S. arguments in the Global South about rules-based order and non-aggression.

Friction with allies

Europe: most EU states would distance themselves from any overt coercive operation against Cuba, recalling Bay of Pigs as an irresponsible gamble; they may refuse to cooperate on sanctions or reconstruction.

Latin America: even right-leaning governments would fear domestic backlash and refuse to be seen as accomplices. The OAS could split, with some recalling its role during early 1960s crises and refusing to repeat that history.

The net effect: U.S. appears isolated, not leading a coalition.

International law, war-crimes and accountability narratives

A Caracas-style raid plus expanded covert action on Cuban territory would raise:

- questions about aggression under the UN Charter;

- potential claims of civilian casualties, targeted killings, sabotage of infrastructure.

Adversaries and NGOs could frame the operation as a 21st-century Bay of Pigs plus “Mongoose 2.0”, adding human-rights language that didn’t exist in 1961 at current strength.

Escalation and Long-Term Security Risks Triggering a crisis comparable to, or worse than, 1962

The original Bay of Pigs indirectly led to the Cuban Missile Crisis as Castro sought stronger Soviet protection.

In our scenario:

Beijing and Moscow could respond by deploying more advanced ISR assets, cyber units, or even dual-capable missiles to friendly states in the wider region (Nicaragua, Venezuela under a future leadership if relations sour again, or Caribbean micro-states);

the U.S. and adversaries might stumble into a high-stakes Caribbean standoff—with far faster missiles, satellites, and cyber tools than in 1962.

Regional destabilization and migration shocks

A partial or failed dismantling of Cuban authority could produce:

- violent power struggles between regime factions, criminal groups, and proto-warlords;

- maritime refugee flows toward Florida comparable to or greater than Mariel and the 1994 crisis combined.

This would be framed domestically as a self-inflicted border catastrophe, directly linked to the decision to “redo” Bay of Pigs.

“Pig Bay” Checklist: Key Red Flags for U.S. Planners

From a Bay of Pigs perspective, U.S. decision-makers should treat the following as red warning lights:

Assuming spontaneous uprising once pressure starts.

Depending on deniability while planning an operation that everyone recognizes as U.S.-driven.

Relying on exile groups’ optimism and intelligence without harsh independent validation.

No clear plan for day-after governance, humanitarian aid, and migration control.

Underestimating the probability that adversaries (China, Russia) will counter-escalate in the region.

Beyond Venezuela and Cuba themselves, the symbolic and strategic messaging is what truly matters. A U.S. operation in Caracas and the credible threat of one against Cuba send extremely powerful signals to Putin and other regimes hostile to Washington. They reshape perceptions of U.S. will, doctrine, escalation readiness, and acceptable norms of regime coercion.

Signal of Restored U.S. Willingness to Use Force for Regime Outcomes

Message to Putin

The U.S. is willing to act unilaterally and decisively in the Western Hemisphere.

Washington is no longer trapped in “post-Iraq caution”; instead, it demonstrates Cold War-era confidence and readiness to directly change political realities.

This counters the Kremlin’s long-standing belief that the U.S. fears escalation, casualties, and legal complications.

Implication:

Putin now has to consider that the U.S. might one day replicate pressure tactics closer to Russian interests—against Syrian proxies, African Wagner assets, Transnistrian influence, or Kremlin-aligned dictators.

Signal of “Monroe Doctrine 2.0”

The Caracas operation revived the core strategic reality:

The Western Hemisphere is once again a U.S. strategic protectorate.

Message to hostile regimes

Cuba, Nicaragua, and left-populist governments are being warned:

foreign alliances with Russia, China, Iran now carry serious personal survival risks.

Any attempt to position strategic intelligence, naval facilities, or missile presence near U.S. territory is no longer tolerated.

For Putin specifically:

Moscow’s return to the Caribbean as a geopolitical theater is no longer risk-free theater; it now carries military exposure.

Russian projection via Cuba and Venezuelan platforms is suddenly fragile.

Signal That “Authoritarian Insurance Policies” Are Not Reliable

For two decades, many regimes believed:

Hosting Russian or Chinese intelligence,

Buying Russian arms,

Supporting anti-U.S. rhetoric,

granted them deterrence against U.S. pressure.

Caracas shattered that assumption.

What they learn now

Russian protection did not save Maduro.

Russian/Chinese presence in Cuba might not save Díaz-Canel.

Moscow’s ability to materially defend allies outside active Russian theaters is limited.

This damages Russia’s prestige as a protector state, particularly across:

Latin America;

Africa;

Middle East.

Signal of Strategic Tempo Change — U.S. Sets the Agenda Again

Putin has spent years dictating crises (Crimea, Syria, Africa, Ukraine).

Caracas suggests a reversal:

U.S. can seize initiative.

U.S. can act without waiting for consensus or international legitimization.

Washington can impose surprise, speed, and psychological shock.

For authoritarian leaders, this means:

The U.S. is unpredictable again.

Decision cycles accelerate.

Defensive paranoia rises inside regimes.

Signal That “Deniability Era” May Be Ending

Both Maduro and Cuba operated under “grey-zone” shelter:

covert influence;

proxy operations;

hybrid warfare.

The U.S. response was historically:

sanctions,

rhetoric,

slow diplomacy.

Caracas changed that equation.

Message sent

If you rely on:

hybrid support from Russia/China,

election manipulation,

repression,

you may now face direct physical decapitation risk, not just economic cost.

For regimes like:

Iran;

North Korea;

Belarus;

Assad’s Syria;

some African autocracies.

This is a psychological shock.

Signal of Personal Risk to Dictators

For Putin especially, the message is deeply personal.

Caracas demonstrated:

Leaders once seen as untouchable can be captured or removed.

Regime decapitation is again legitimate in Washington’s thinking.

Personal security of leaders hostile to the U.S. cannot be assumed eternal.

This creates:

paranoia inside ruling elites,

increased purges,

fear of betrayal,

loyalty stress within militaries and intelligence services.

Insecure dictators become more brutal internally — but also more cautious internationally.

Signal to Adversary Networks: Your Strategic Depth Is Collapsing

Caracas weakened:

Russian intelligence infrastructure in Latin America;

Cuban-Venezuelan repression axis;

narcotrafficking networks aligned with political power;

proxy diplomacy structures.

If Cuba is next, adversarial strategists conclude:

The U.S. is dismantling geopolitical infrastructure, not just governments.

This sends shockwaves to:

Russia’s African operations,

Iran’s regional networks,

Chinese SIGINT expansion.

They now fear systemic rollback.

But There Is Also a Dangerous Counter-Signal

While projecting strength, Washington also risks sending another message:

To Putin and hostile regimes:

If you want security from U.S. intervention, deepen alignment with China/Russia militarily.

Accelerate acquisition of nuclear deterrence.

Harden authoritarian repression immediately.

This may:

- push states toward militarization,

- accelerate Russian-Chinese military cooperation,

- normalize hostile basing near U.S. territory as a counter-threat.

So the deterrence signal comes with escalation risk.

Operations in Caracas — and the credible signaling toward Cuba — transmit to Putin and hostile regimes:

The U.S. has regained willingness to forcibly shape political outcomes.

The Western Hemisphere is again a protected American sphere.

Russian/Chinese security guarantees are unreliable shields.

Authoritarian regimes aligned against Washington now face existential personal risk.

Global strategic tempo shifts—Washington is back in initiative mode.

But this also pressures hostile regimes to harden, militarize, and deepen alignment against the U.S.

Caracas Operation as a Symbol of the CIA’s “Return”

The U.S. operation in Caracas functions not only as a military or political event but as a strategic symbol: it signals the perceived return of U.S. covert power projection, particularly associated with the Central Intelligence Agency’s historic role in regime shaping. Whether the CIA actually led operational execution is less important than global perception. In geopolitics, symbols matter as much as capacity.

1. Restoration of Reputation After a Long Period of Strategic Hesitation

For much of the post-Iraq and post-Afghanistan era, the CIA was widely seen by adversaries as politically constrained, legally restrained, and strategically defensive. Washington favored sanctions, diplomacy, and technological warfare rather than direct regime outcomes.

The Caracas operation changes that equation. It suggests:

The U.S. is once again willing to shape political realities, not merely react to them.

Covert and special operations capacity is re-legitimized as an instrument of national strategy.

The psychological aura of the CIA — damaged by intelligence controversies, internal restructuring, and political mistrust — is revived through success, not rhetoric.

To hostile regimes, this looks like the return of Cold War-style agency confidence, even if modern operations are technologically and legally different.

Revival of a Historical Narrative: “The Americans Are Back in the Business of Changing Regimes”

Caracas symbolically echoes earlier U.S. interventions:

Iran (1953);

Guatemala (1954);

Chile (1973).

Covert operations in Latin America during the Cold War.

The psychological effect is powerful. Leaders hostile to Washington interpret Caracas as proof that history has resumed: the U.S. will once again punish disobedient regimes, remove unfriendly strongmen, and enforce a hemispheric strategic order.

This feeds a perception that:

The CIA is no longer a “defensive bureaucracy,” but a strategic hunter.

Neutrality and distance are illusions — Washington is prepared to act decisively.

Fear as a Strategic Instrument

More important than what the CIA did is what hostile leaders now believe it can do.

The Caracas precedent amplifies fear in:

Cuba;

Nicaragua;

authoritarian South American systems;

African regimes supported by Russia;

Middle Eastern partners aligned with Moscow or Tehran.

Dictators will now:

purge their security services more aggressively;

search for “CIA penetration”;

distrust their generals;

tighten repression pre-emptively.

Fear becomes a policy multiplier for Washington. Without firing additional shots, the Caracas operation forces adversarial regimes into paranoia, self-defensive extremism, and internal instability.

Strategic Humiliation of Russia and Exposure of Its Limits

For years, Russia portrayed itself as protector of anti-U.S. regimes, backed by Wagner, intelligence presence, and political theater. Caracas demonstrated:

- Russian backing does not guarantee survival.

- Moscow cannot protect allies in Washington’s neighborhood.

- Russian deterrence narrative collapses in real crisis.

Symbolically, this re-elevates the CIA as the more reliable force in regime competition and downgrades Russia as a security guarantor. This message resonates deeply in:

Africa (where Russian influence is expanding);

Asia (where regimes hedge between U.S., China, and Russia);

Latin America (where symbolic power matters).

“Monroe Doctrine Enforcement Arm” Image Reborn

For decades, the CIA was not merely an intelligence agency in Latin America; it was perceived as the operational enforcement instrument of U.S. hemispheric doctrine.

Caracas revives that archetype:

The CIA is once again the guardian of American geopolitical order in the Western Hemisphere.

This creates:

deterrence for hostile actors

obedience incentives for uncertain regimes

psychological discipline within the regional political system

It signals that the hemisphere is closing to adversarial encroachment — not through diplomacy, but through capacity.

But the Symbol Comes With Strategic Risks

While powerful, this symbolic resurrection is dangerous.

It may:

- Encourage dictators to militarize faster.

- Push hostile states toward China for security guarantees.

- Inspire retaliation in Ukraine, Middle East, Africa, cyberspace.

- Fuel anti-U.S. narratives across the Global South (“imperialist overthrow machine returns”).

There is also Bay of Pigs risk psychology:

If Cuba becomes the next theater and fails, the mythical CIA aura collapses immediately.

The Caracas operation did more than remove a regime leader. It revived the mythic and strategic identity of the CIA as an active force capable of decisive outcomes, re-establishing U.S. covert power credibility after years of caution and perceived decline. For Putin, authoritarian leaders, and anti-U.S. regimes, the message is unmistakable:The age of American covert passivity is over. The CIA — as symbol, deterrent, and psychological weapon — has returned.

More on this story: Cuba actively sabotaging Latin American democracies (audio)

More on this story: Cuba protests: Havana regime cracks but tries to keep afloat with outside help

More on this story: Will Trump’s Plan to Reform the CIA succeed?

More on this story: China likely to share SIGINT with Russians

More on this story: Putin trying to replay Cold War in his favor

More on this story: Russia uses Venezuela as foothold to stage operations against Brazil

More on this story: Government and paramilitary groups behind human rights violation in Venezuela