The ceremonial launch of the first concrete pour for Unit 5 of the Paks II Nuclear Power Plant was staged with great pomp and, according to the plan of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s government, was meant to symbolize technological progress and a step toward Hungary’s energy independence. In reality, however, the Paks Nuclear Power Plant—located about 100 kilometers south of Budapest—currently operates four Soviet-designed VVER-440 reactors that were commissioned between 1982 and 1987.

In early 2014, a Hungarian–Russian intergovernmental agreement was signed under which Russian enterprises were to supply two VVER-1200 reactors for the Paks II project. The agreement also provided for a Russian state loan of up to €10 billion to finance approximately 80% of the project’s cost.

Russia’s state corporation Rosatom, which is responsible for construction, stated at the permitting stage for the first concrete pour that the licenses “confirm compliance of the project with strict international, European, and national nuclear safety requirements.”

In reality, according to internal reports by Rosatom specialists, the excavation pit on which the future unit is being built is already showing alarming signs of deterioration. Cracks, ochre-colored deposits, and the characteristic smell of hydrogen sulfide are not random defects, but symptoms of deep-seated processes that threaten the long-term durability of the entire structure.

The reinforced soil material, saturated with a cementitious mixture, is comparable to concrete in strength. However, it contains significant quantities of sulfates, which continue to accumulate over time due to filtration water. This combination creates conditions for the development of Type III internal corrosion, namely the formation of secondary ettringite.

Ettringite—a product of cement hydration—has a larger volume than other components, and its formation leads to internal stresses and the gradual destruction of the material’s structure. In other words, the soil foundation that was supposed to guarantee stability becomes a source of future deformation. This is not a hypothetical scenario, but a well-established pattern confirmed by experience with other engineering structures.

Research by A. Blanco, F. Pardo-Bosch, S. Cavalaro, and A. Aguado on corrosion processes in dams demonstrates that cracking, ochre deposits, and deformation are direct consequences of sulfate attack.

In one case study of a concrete dam built between 1968 and 1971, the first signs of corrosion—displacements and deformation of individual structural elements—were recorded as early as 1981. In 1993, microstructural analysis confirmed the presence of secondary ettringite. Over the following years, the concrete structures underwent critical deformation. Over a 17-year period, horizontal displacements of the dam crest nearly tripled, while vertical displacements increased fivefold.

If similar processes are already being observed in the excavation pit at Paks II—as noted in an internal Rosatom document—then within 10–20 years the concrete structures of Unit 5 may experience critical deformation.

This would represent not merely a technical issue, but a real threat to the safety of people living near the facility. In the case of a nuclear power plant, even minor structural defects can have catastrophic consequences, given the inherently high-risk nature of such installations.

The situation is further aggravated by the lack of continuity in the reinforced soil mass. Filtration waters containing sulfates penetrate through it to the concrete base. If ordinary, non-sulfate-resistant cement is used—without special additives to enhance corrosion resistance—the concrete foundation will inevitably be exposed to destructive processes.

The formation of secondary ettringite in the concrete will lead to gradual deformation that, over time, will destroy the foundation of the reactor unit. This means that future accident risks are being built into the nuclear power plant already at the construction stage.

Experience with Russian contractors in critical infrastructure projects has repeatedly demonstrated problems with quality, transparency, and accountability.

Nevertheless, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán appears willing to ignore any violations and risks, using the construction of Paks II as a tool for personal enrichment by diverting part of the funds for his own benefit. For him, the priority is the realization of a project that generates political dividends and financial gains.

Unofficially, Rosatom engineers acknowledge that within 10–20 years the concrete structures of the plant will undergo critical deformation, rendering the station structurally unstable and creating the risk of a major accident due to loss of containment integrity (the reactor’s protective structure).

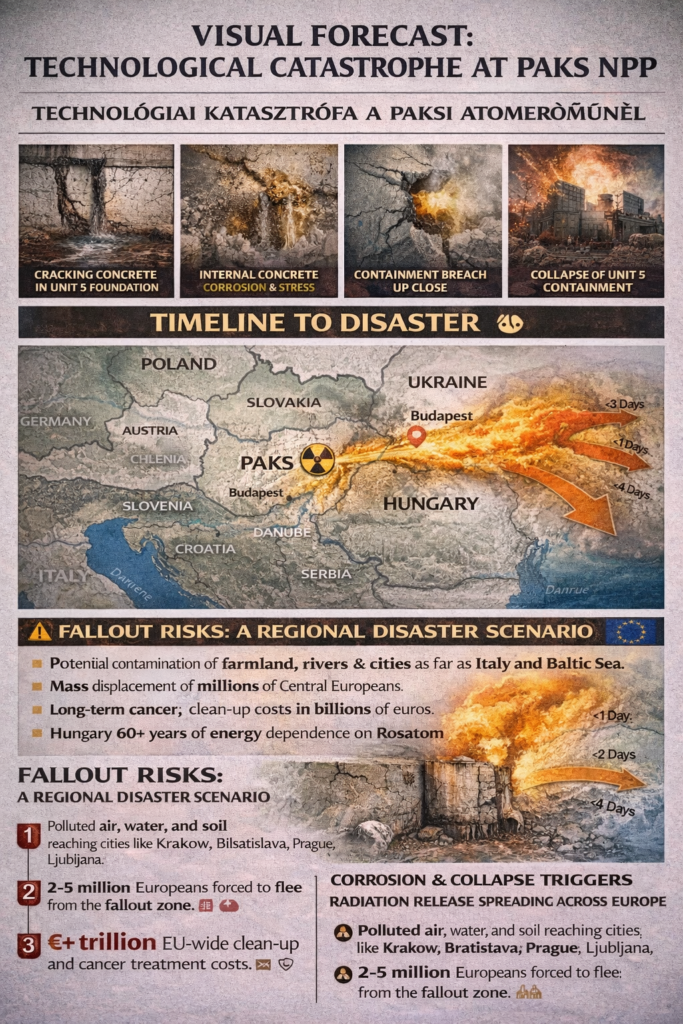

In the event of an accident at Paks II caused by defects embedded today, the consequences would be felt across Europe. Contaminated air and water could reach Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Italy, Austria, Germany, Romania, Ukraine, the Baltic Sea, the Alpine region, and even the Mediterranean. Central Europe risks becoming a zone of man-made disaster, forcing millions of people to abandon their homes due to Rosatom’s negligence and Orbán’s corruption.

A potential accident at Paks II would contaminate agricultural land in Poland, halt industrial activity in Germany, and devastate tourism in the Balkans. The costs of remediation—borne by European taxpayers—would amount to trillions of euros. A single corrupt project could trigger long-term economic depression and social crisis across the region.

The Paks II project also serves as an instrument of the Kremlin’s long-term political influence over the European Union. Instead of investing in energy efficiency or renewable sources, Hungary is voluntarily locking itself into a 60-year dependence on Russian fuel, services, and credit. This makes Budapest a hostage to Rosatom, whose operating standards directly threaten Europe’s radiation safety.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) appears to turn a blind eye to these obvious risks. By calling the day of pouring defective concrete “a great day for Russia,” international institutions effectively legitimize danger. The European community must demand an end to the policy of double standards: nuclear safety cannot be a subject of political compromise when Central Europe risks becoming a new exclusion zone.

For Orbán, this is particularly important ahead of the parliamentary elections scheduled for 12 April, which will determine his political future. He is determined to win at any cost—even if that means ignoring future problems at Paks II and the risk of human casualties.

The price of such cynical governance may be extremely high: destruction of a reactor unit, threats to human life, and severe reputational damage to the country. The very act of pouring first concrete into a cracked excavation pit has become a symbol of a government that places profit above life.

For the European Union, Paks II is a test not only of technical competence, but of political responsibility. The defects in the excavation pit are not merely an engineering issue; they symbolize cracks in European solidarity, which is increasingly sacrificed to political compromise and short-term gain. If obvious risks can be ignored even in nuclear energy, the question is no longer only about Hungary’s energy future, but about Europe’s ability to protect itself from decay from within.

Key corruption and governance concerns

A) Lack of transparent procurement processes

- The Paks II contract structure is non-competitive and opaque:

- Rosatom was selected without international tendering.

- Major subcontractors and suppliers are predominantly Russian or linked entities, raising questions about cost benchmarks and competitive pricing.

- International procurement norms (competitive bidding, open audits) were largely bypassed in favor of direct government-to-government arrangements.

Risk: Inflated costs, hidden kickbacks, and no independent cost control.

Source: EU Parliament reports and analysts highlight the lack of transparency in Russia–Hungary nuclear deals.

B) Fixed-price construction anomalies

- Rosatom offered a “turnkey, fixed-price” framework — appealing politically, but ambiguous because it is not fully verified by independent auditors.

- Fixed pricing in such highly complex projects often creates incentives to off-load costs to subcontractors where margins and markups are opaque.

Risk: Hidden cost overruns and cost shifting to Hungarian taxpayers without accountability.

C) State capture and political patronage

Politically, Paks II is closely associated with Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and the governing Fidesz party:

- It is widely viewed as a symbolic prestige project for the government, boosting domestic political capital.

- The project reinforces a geopolitical alignment with Moscow, which critics characterize as part of a broader capture of strategic infrastructure by political elites.

Risk: Project decisions prioritized for political gain rather than public interest or economic rationality.

D) Violation of EU competition and state aid rules

Multiple critics — including the European Commissioner for Competition — have argued that the state financing model and the direct award to Rosatom raise concerns under EU competition and state aid law.

Hungary’s ability to justify the model under EU rules has been scrutinized and criticized, although formal legal actions have been limited due to political sensitivities within the EU.

E) Allegations of opaque consulting and advisory contracts

Various consultancy contracts, feasibility studies, and strategic advisory services around Paks II have been awarded with minimal disclosure — including contracts involving political allies of the governing party.

Risk: Advisory fees routed through associated firms without competitive tendering.

F) Parliamentary oversight and accountability weaknesses

- Parliamentary oversight committees have been criticized for limited powers, lack of independent expertise, and partisanship.

- Project reports and audits are often produced by stakeholders or entities with ties to the government rather than independent bodies.

Risk: Limited transparency reduces public accountability and increases corruption vulnerability.

What external institutions have said

European Commission

- Has repeatedly emphasized transparency, EU state aid compliance, and competitive neutrality.

- The Commission’s Competition authority stated that the financial structure (including the Russian loan) should be compliant with EU law, but many experts see this as a political compromise rather than a substantive guarantee.

International Transparency & watchdogs

- Organizations like Transparency International have flagged increased corruption risks in large infrastructure projects in Hungary — including Paks II — due to centralized decision making, weak procurement oversight, and political influence over regulation.

Specific allegations or controversies raised in media & reporting

Below are some of the most recurring themes — not all are independently proven, but they reflect systemic concerns raised in credible reporting:

A) Cost inflation and hidden financing terms

Some investigative outlets and analysts argue that the real cost of Paks II (including interest on the Russian loan, scope changes, and inflation provisions) may far exceed publicly disclosed figures — with limited independent verification.

B) Links to oligarch networks

Critics have pointed to the involvement of contractors and intermediaries close to political elites whose firms have benefited from subcontracts without transparent tendering.

C) Strategic affinity with Russia

While not “corruption” in a narrow sense, many observers treat the geopolitical alignment and favorable conditions extended to Rosatom as a form of state-level rent seeking and political benefit, blurring political and economic logic.

Technical concerns and safety claims

Some opposition and civil society actors — as reflected in the article you asked me to translate earlier — argue that structural and engineering issues (e.g., concrete quality, geological faults) are being ignored or downplayed.

While such claims deserve technical assessment by independent nuclear engineering authorities, the governance riskhere is that safety and quality auditing may be compromised by political imperatives, further exacerbating corruption vulnerabilities.

Are there formal corruption investigations?

To this point:

- No major, publicly transparent criminal investigation into Paks II has resulted in indictments related to corruption or bribery.

- However, parliamentary investigations, audit gaps, and NGO reports all point to structural corruption risk factors:

- Lack of competitive tendering;

- Politicized oversight;

- Opaque financing and contract awards;

- Concentration of decision making in executive prerogative.

In effect, the situation reflects governance risk and political economy vulnerabilities, even if direct judicial findings of corruption have not been made.

How corruption risk ties to broader political dynamics

Paks II is often discussed not just as an energy project but as a political economy symbol of:

- Executive dominance under Viktor Orbán’s government

- State control over strategic sectors

- Political centralization and weakened independent institutions

In this broader pattern, critics argue that:

- Major infrastructure and defense contracts are increasingly concentrated among government-affiliated entities

- Procurement and oversight mechanisms that would constrain corruption are weakened

- Political loyalty and symbolic victories (such as “Russia partnership continuity”) take precedence over economic and technical rationality.

The Paks II nuclear project is not yet proven to be a corruption case in a strict legal sense, but it is widely recognized as a high-corruption-risk infrastructure project due to:

- Opaqueness in procurement and financing;

- Political prioritization overriding competitive norms;

- Weak independent oversight;

- Close linkages between political elites and implementation structures

In governance terms, the real “corruption story” is not (yet) a courthouse indictment but rather a structural pattern of elite influence, lack of transparency, and weak accountability around a strategically significant national project.

Quick comparison: where “corruption risk” tends to concentrate

| Project | Delivery model | Main corruption / governance risk pattern | Signature controversy |

| Paks II (Hungary) | Direct award (Rosatom) + state-backed structure | Procurement opacity + geopolitical capture risk (single supplier; weak price discovery; limited competitive benchmarking) | EU legal scrutiny over direct award without tender and state-aid/procurement compliance |

| Flamanville 3 (France) | State-owned utility/industry build (EDF/Framatome ecosystem) | Mismanagement / weak industrial governance more than classic bribery: cost discipline failures, quality-control breakdowns, poor reporting | Massive overruns and poor profitability flagged by Cour des comptes (France’s Court of Accounts) |

| Hinkley Point C (UK) | Private-led project + heavy state support (CfD) | Policy / value-for-money risk: long-term consumer lock-in, complex contract design, oversight challenges | NAO: deal is risky/expensive; large long-term consumer exposure; governance and risk-management concerns |

Paks II: the “procurement + geopolitical leverage” risk profile

What makes Paks II distinct is not that it’s the only project with overruns or controversy—it’s that the governance red flag is upstream: how the supplier and contract were chosen, and how that shapes transparency, price discovery, and political accountability.

- The European Commission’s 2017 state-aid decision and subsequent litigation are central to understanding the governance critique: the project’s direct award to a Russian contractor without a public tender became a core issue.

- In September 2025, the EU Court of Justice faulted the Commission for not properly assessing whether the direct award complied with EU procurement rules—this is an institutional red flag about process integrity and oversight.

Corruption-risk takeaway (analytical):

When a strategic project is awarded through a single-supplier, politically anchored pathway, the main vulnerability is not only bribery—it’s structural rent creation: inflated subcontracting margins, weak competitive constraints, and the ability to use the project as political patronage.

Flamanville 3: the “industrial governance failure” model

Flamanville 3 is the classic European example where the scandal is less about corruption and more about state-industry mismanagement and accountability gaps.

- France’s Cour des comptes estimates total cost around €23.7 billion (2023) and describes weak profitability; it also criticizes cost monitoring and transparency (including incomplete information from EDF).

Corruption-risk takeaway:

This is primarily a governance/competence problem (cost discipline, quality controls, reporting), which can still produce corruption-like outcomes (waste, captured oversight), but it is not principally driven by opaque supplier selection.

Hinkley Point C: the “contract design and long-term burden” risk profile

Hinkley is less about procurement opacity and more about whether the state struck a good deal—and whether oversight mechanisms protect the public over decades.

- The UK National Audit Office (NAO) found the government’s deal exposed consumers/taxpayers to substantial long-term cost and risk, with the critique focusing on value-for-money, the difficulty of renegotiation, and the scale of future commitments.

- More recent reporting highlights continued delays and cost escalation, reinforcing the NAO’s original risk logic.

Corruption-risk takeaway:

Hinkley’s “corruption-adjacent” vulnerability is policy capture via complex contracts: even without bribery, contract structures can lock in rents and reduce democratic control over future costs.

What this comparison implies for “corruption on Paks”

If you’re building a corruption-risk argument, the strongest comparative claim is:

- Paks II resembles a high political-capture / low-transparency model (supplier selection and geopolitical dependence are the core risk).

- Flamanville 3 resembles a state-industry governance failure model (mismanagement, quality, accountability).

Hinkley Point C resembles a contractual lock-in / consumer exposure model (value-for-money and oversight).

More on this story: Rosatom violates non-proliferation treaty in Iran

More on this story: Russia Exploits the IAEA to Steal Chinese Nuclear Technology

More on this story: From Delays to Dependence: Understanding the Challenges of Russian NPPs