Corruption is generally thought to cripple the economy and reduce foreign investment quote required for economic development. Russia and China have managed to see corruption as a window of opportunity to heighten their national interest and are conveniently exporting it to third world countries as a way of geoeconomic expansion.

Corruption remains an immanent feature of the Chinese and Russian elites despite claims and multiple strategies. It is well-organized, has got a clear “price-list”, where almost every high official shares in. High-profile bribery cases are mainly triggered by colliding interests of elites, amid clan rivalry. Then the act of corruption is made public, and the perpetrators (but not the final beneficiaries, as a rule) are punished. Fight against corruption in these countries, therefore, is just external, tenuous, demonstrative. Method of tampering with elites is, in turn, exported dynamically to where it is possible to implement it.

China and Russia traditionally rank #1 internationally in using dishonest business methods abroad. The same tactic is used for geo-economic and geopolitical expansion, when state-owned companies or people representing the state provide bribes for national governments and leaders.

China and Russia use this method for transitional democracies or authoritarian dictatorships. That is, where the information leakage risk is minimal. This is basically possible just when the elites of beneficiary state change, and this information is used to discredit the predecessors. The leakage is one-time only, as a rule, and then the representatives of Moscow and Beijing “find the key” to the new elites, tampering with them too. Bribery cases involving Russia and China rarely get passed around in the media, therefore. The most high-profile recent ones are:

• railway construction and operation scandal in Mombasa (Kenya) ;

• peculiar relations between Chinese CNPC and Uzbekneftegaz (Uzbekistan);

• gold mining by Chinese “Kichi-Chaarat” in Kyrgyzstan;

• “Andrei Vtyurin” case (telecommunication equipment and software supplies from Russian companies in Belarus), etc.

China and Russia tackle several tasks at once by tampering with local elites.

First, they can pursue effective geo-economic expansion in this way, showing higher competition compared to Western partners. This adds to more effective fight for resources and pursuit of interest.

Secondly, proper special agencies usually monitor and record the funds or other benefits being transferred. Therefore, they seek incriminatory evidence on the political elite and officials of the recipient state, then used to recruit or put the screws on them.

Thirdly, such transactions are lucrative for representatives of the expanding state or representatives of companies representing the state as well, as they foresee their own benefit in each of them and enrich themselves illegally.

These three factors altogether make the corruption-export strategy to partner states effective for the state that is expanding. That, in turn, overhauls the development path for the recipient state and affects social evolution.

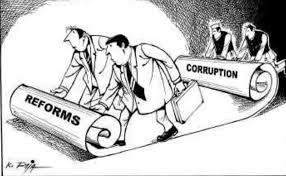

Sponsorship of corruption hampers democratic change and reform, providing those were carried out or planned.

National elites successfully tampered with by Beijing or Moscow eventually become fully dependent on them. This boosts neocolonization.

Russia and China are seeking not to change the elites they have tampered with. Thus, they de facto back authoritarian regimes or national leaders. This, in turn, triggers social imbalance and hinders the development significantly. Moscow and Beijing, therefore, not just guard their interests and increase their competitiveness in the 21st century struggle for resources by exporting corruption. They also widen the gap between rich and poor countries, throwing the latter back forever, in fact, preventing them from developing. These countries will subsequently become a global supplier of unskilled or low-skilled labor force.