When the United States started the negotiations with the Taliban, the scale of hostilities decreased, but later the Taliban resumed participation in attacks. It was in the second half of 2019 that anti-government forces increased their activity.

The distribution of attacks in various parts of the country remained largely the same: active fighting took place in the southern and western provinces while in the North and East of Afghanistan the areas of militant activity expanded.

However, the Afghan defense ministry denied that Taliban attacks were on the rise. There are doubts in an Afghan defense ministry spokesman Farwan Aman’s statements that the Taliban are no longer able to carry out offensive operations. They still able to carry insurgency and guerrilla ops a countryside, roads and terrorist attacks on Afghan cities.

The majority of casualties among Afghan forces, like in previous years, came from Taliban attacks on checkpoints. Though the insurgent group has focused less on urban areas, it has ramped up attacks in the countryside.

The increase in the number of attacks began in September, the month of preparation and holding of presidential elections, during which anti-government forces repeatedly carried out attacks and sabotage in order to disrupt the vote. According to the Resolute Support mission, last September was the month with the highest number of attacks since June 2012 and the highest number of successful attacks since January 2010. October 2019 accounted for the largest number of attacks since July 2013.

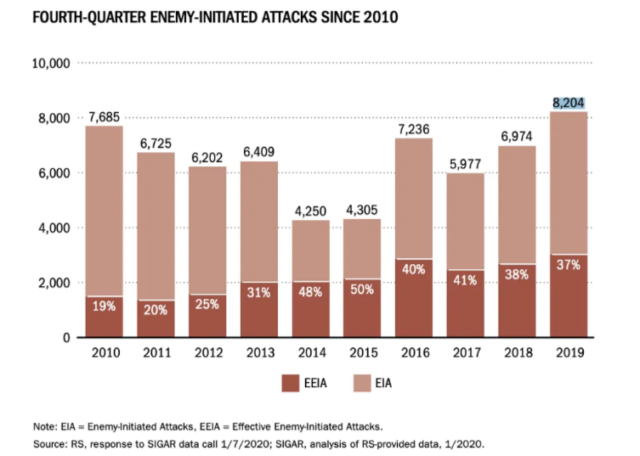

The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) recently published the quarterly report which highlights that over the last quarter of 2019 the number of Taliban attacks in Afghanistan increased by 17% compared to the same period in 2018. The high level of attacks conducted by the Taliban might seriously threaten the dialogue on the peace agreement started by the United States.

In particular, the number of Taliban attacks in October, November and December 2019 reached 8,204, compared to 6,974 in the last three months of 2018. In the second half of 2019, compared to the same period in 2018, the number of attacks increased by 6%, and successful attacks by 4%.

Currently, the United States is preparing to sign a peace agreement with the Taliban, but so far the militants regularly carry out attacks on the Afghan guards. According to the US Secretary of state Mike Pompeo, in order to sign a peace agreement, the Taliban must demonstrate in practice their readiness to reduce the level of violence.

The Afghan government wants a monthlong cease-fire, and the Taliban has scaled back some attacks — but only on cities and main roads.

A Defense Department official attributed the higher number of Taliban attacks in the inspector general’s report to the fact that the insurgents were attacking more frequently, albeit in small numbers — a byproduct of the American air campaign and joint United States-Afghanistan ground missions.

Ultimately, the Taliban want a complete withdrawal of American troops, while the Americans eventually want joint talks between the Taliban and other Afghans over power-sharing in the government.

The president Trump has made no secret of his antipathy for the Afghanistan war. Since 2017 Trump complained that withdrawal from Afghanistan (and Iraq) would make him “look weak” and “look soft,” something entirely anathema to Trump.

The logic of Trump’s escalation: that intensified fighting is necessary to compel the Taliban to agree to terms. But the war didn’t drive the Taliban to the table. Airstrikes force them to turn to guerrilla warfare, and to the activity of hidden terrorist cells. Their elimination requires a serious presence on the ground.

The Tailban’s choices associated with Pakistan’s enormous influence on the movement. Pakistan has spent the last dozen years in an increasingly untenable position, caught in the crossfire between the US, and its most useful client, the Taliban. It has proved unwilling to give up either relationship even in the face of attacks in its own territory – whether by Pakistani Taliban sympathisers or US forces. On one hand, since the country’s birth in 1947, Pakistan’s leadership has seen American aid, expertise and diplomatic support as vital to national survival. On the other hand, since 1971, when the country’s eastern half broke off to become Bangladesh, Islamabad has feared its western provinces on the Afghan border might also be torn away, enticed by ethnic links to Afghanistan’s Pashtuns. The only inoculation from irredentism, in Pakistan’s eyes, is the cultivation of Afghan allies who can manage Kabul for it.

the Pakistani establishment has reconciled itself to a power-sharing arrangement that constrains the Taliban’s power. The Pakistan Army has used its considerable leverage to persuade a reluctant Taliban leadership to take up a similar view.

Mr Trump’s firing of General HR McMaster as US national security adviser in 2018 was the turning point Pakistan had been waiting for. It marked the end of Pentagon influence in the Oval Office, and Pakistan’s relationship with the Taliban turned from a liability into an asset overnight. Prime Minister Imran Khan has been rewarded with a visit to Washington and a resumption of training and technical support for Pakistan’s armed forces– a change after years of cuts in US military aid. All of this has been especially vital at a time when Pakistan’s economy is struggling and its military skirmishes with its southern neighbor have reached a level of intensity not seen in almost 20 years.

Any deal the US makes with the Taliban is likely to significantly empower the latter.

Pakistan, would succeed in its mission to give its client a powerful seat in Kabul, while benefiting from Washington’s subsequent satisfaction that US troops can go home. If the Taliban’s seat at the table is too powerful, however, the price would be paid by Afghan women, minorities and other groups it has long oppressed.