Myanmar coup followed agreements made between the military leaders of Myanmar and the official Beijing seeking more influence in Myanmar and kicking out India as a competitor in the region. The coup coincided with both the domestic agenda in Myanmar and President Joe Biden’ inauguration.

Myanmar’s military staged a coup on Monday and detained the country’s senior politicians including the Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. The takeover is a sharp reversal of the significant, if uneven, progress toward democracy the Southeast Asian nation has made following five decades of military rule.

Commander-in-Chief Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing would rule the country for one year. According to mil, the takeover was necessary because of the government’s failure to act on the military’s claims of voter fraud in last November’s elections (when Suu Kyi’s ruling party won a majority of the parliamentary seats up for grabs), and its ‘green light’ to go ahead with the elections despite the coronavirus pandemic.

The military is dissatisfied with the results of the opposition ultra-right party Union Solidarity and Development Party backed by the army leaders. Official figures show that the Aung San Suu Kyi party won the last November elections with 83% of the vote. The military claims that the electoral rolls were forged and 8 million illegal votes were counted.

One of the coup key triggers was Min Aung Hlaing’s early possible resignation from the post of commander-in-chief (in July he turns 65. He was supposed to retire but he will rule the country until at least February 1, 2022). The takeover day was scheduled for the first parliamentary session since the elections. The session participants were supposed to approve new government and the elections results.

Suu Kyi had been a fierce antagonist of the army despite house arrest, since her release and return to politics, she has had to work with the country’s generals, who never fully gave up power. Suu Kyi’s deference to the generals going so far as to defend their crackdown on Rohingya Muslims minority that the United States and others have labeled genocide — has left her reputation internationally in tatters.

In 1990, her party won the parliamentary elections, but the military did not want to give up power: they canceled the elections results and arrested Suu Kyi. She had lived under house arrest for years as she tried to lead her country toward democracy and then de facto became its leader after her National League for Democracy won elections in 2015.

The coup is confirmation that the military holds ultimate power despite the veneer of democracy.

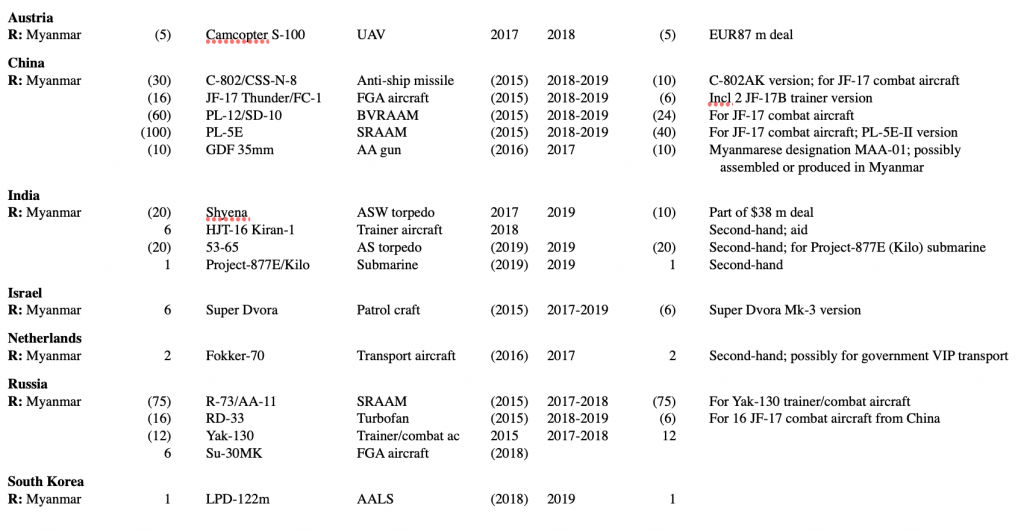

The analysis also points to China’s external influence on Myanmar’s military. Beijing is one of the country’s main weapon suppliers.

India sees Myanmar as strategic partner. However, the coup can change a lot of things. The imposition of sanctions against the military junta regime could push Myanmar into China’s influence zone. Apparently, Beijing is already considering this prospect. This is the reason why it does not criticize the coup and blocked the UN decision. The establishment of an undemocratic regime on its borders is not bad news for China. There is a high probability that China might have backed the takeover. The Myanmar military would hardly have dared to overthrow the regime without the support and approval of Beijing.

Beijing was close enough to the civilian leadership of Myanmar; it served as an observer in the Myanmar and Bangladesh negotiations regarding the Rohingya Muslims minority. It has monopolized the Burmese market and has become the country’s second investor. In turn, Myanmar gives China an access to Andaman sea. After sanctions being imposed, Myanmar’s dependence on the Chinese economy will increase exponentially. Thailand will suffer the most from the Myanmar coup. The takeover could also freeze Bangladesh talks on Rohingya future. In fact, the power in Myanmar was taken by the same military force that had committed genocide against Rohingya.

Min Aung Hlaing is suspected of committing crimes in Kachin and Shang states. In these two regions his companies mined jade and rubies; his officers were involved in sexual abuse and forced labor of the local population.

The PRC is the only country having no fear to violate US sanctions. Therefore, Beijing could give protection guarantees to the coup leaders in exchange for preferential advantages in Myanmar. Moreover, China is highly interested in reducing dependence on oil supplies through the Strait of Malacca and controlling of the Kyaukpyu deep-water port in Rakhine State. Some Myanmar civilian officials have questioned the feasibility of the project to dredge the port. In 2019, despite Beijing’s pressure, Myanmar did not unfreeze the construction of hydraulic systems for China’s strategic One Belt – One Road project. The construction resumption indicates clearly China’s involvement in the Myanmar coup.

Although Beijing has maintained good relations with the Suu Kyi government, obviously its geopolitical ambitions push to put a military regime into power – the regime with no democratic boundaries, less dependence on the position of the West, and being totally controlled by China.

The coup leaders themselves may point to reviving the regime like that ruled Myanmar for nearly two decades. Commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing has long wielded significant political influence, successfully maintaining the power of the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s army.

As the coup results, the Vice President Myint Swe, 3rd First Vice President of Myanmar, would be elevated to acting president. Myint Swe is an ethnic Mon, former general best known for leading a brutal crackdown on Buddhist monks in 2007. He is a close ally of Than Shwe, the junta leader who ruled Myanmar for nearly two decades.

The Tatmadaw single-handedly drafted a new constitution in 2008 with a clause allowing the military to appoint its members in the Parliament (up to 25% of seats) and control several Cabinet security and defense related ministries. Thus, this arrangement gives the Tatmadaw the de facto power to veto any constitutional reforms submitted by civilian legislators. Moreover, the Constitution gives the army control over the country’s mining, oil and gas industries, thus ensuring a continuous flow of resources.

The military justify its actions by referring to the article in the constitution it drafted in 2008 that allows it taking over in times of national emergency, though Suu Kyi’s party spokesman said it amounts to a coup.

The military has been the most powerful force in Myanmar (formerly called Burma until the military government changed the country’s name in 1989) since the country’s independence from Britain in 1948. The Tatmadaw continued to enjoy strong public support as the institution that has liberated the nation from colonial oppression. The military enjoyed unchecked control over the country’s political scene from the very beginning. The army also maintains popular support by making lavish donations to the Buddhist sangha, or community, and funding the construction of monastic schools.

Myanmar was emerging from decades of strict military rule and international isolation that began in 1962.

The takeover was just a pretext for the military to reassert their full influence over the political infrastructure of the country and to determine the future, at least in the short term. The generals do not want Suu Kyi to be a part of that future.

U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken expressed “grave concern and alarm” over the reported detentions. “We call on Burmese military leaders to release all government officials and civil society leaders and respect the will of the people of Burma as expressed in democratic elections,” he wrote in a statement, using Myanmar’s former name.