The federal government of Somalia could face sanctions and visa restrictions, to respond to non-productive efforts to undermine peace and stability.

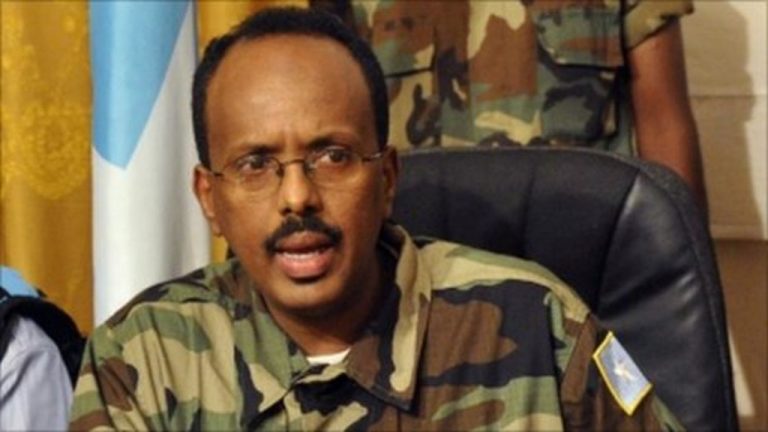

President Farmajo’s efforts to strengthen the presidency have left him isolated from member states whose collaboration is required if a federal system of governance is to survive. His heralded presidency may conclude as a haunting reminder that federalism and strong-arm governance are unlikely partners in Somalia’s tortured path to recovery.

It’s threatening the regional security as Somalia relies heavily on outside help to feed its people, many of whom are internally displaced.

The two houses of parliament clashed on the status of President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo, whose term in office technically expired on February 8.

The lower house of parliament voted overwhelmingly to extend the term of the president and his government by two years in an attempt to end a political crisis after national elections were delayed in early February.

The special session saw 149 MPs vote in favor of the extension, with only three opposed of total 275 MPs. Meanwhile the upper house said the move was unconstitutional.

However, Farmaajo signed the disputed mandate extension into law, even though the resolution was not put before the upper house, which would normally be required. So, the president clings on to power, leaving no political agreement on the current situation. Opposition groups said they would no longer recognise his authority following the expiration of his term.

The decision may undercut the calls by the international community and opposition groups who had opposed extension of mandate and any moves that could jeopardise the implementation of an indirect election based on an agreement reached on September 17, 2020.

A Somali president has never held a second term in office. Every election cycle is contentious, but anger and mistrust between political players have reached new depths and the government is at a perilous point. This is the first time a presidential term has ended before an agreement about how to proceed with an election has been reached.

There is no sign that Somalia’s delayed parliamentary and presidential elections will begin any time soon.

That followed the failure by the Federal Member States (FMS) to support the implementation of the initial Sep. 17, 2020 Agreement. Under the agreement signed by President Farmaajo and leaders of five federal states; an indirect election was to be based on delegates nominated by elders in conjunction with the electoral management bodies. The delegates were to elect MPs who in turn vote for the president. But the parties disagreed on who should be members of the electoral commission, security arrangements and venue of the polls in some of the federal states.

Somalia’s government has been unable for months to reach agreement on how to carry out the election, with the regional states of Puntland and Jubbaland objecting on certain issues.

Farmajo entered office seeking to expand the federal government’s authority over Somalia’s five other federal member states. This effort involved the installation of close confidants to powerful posts across the federal bureaucracy. He made a federal intervention in local state elections — a campaign that powerful incumbents across the various federal member states opposed.

In 2018 and again in 2020, Farmajo’s government reportedly engineered the removal and replacement of key political opponents in the central states of Galmudug, South West, and Hirshabelle. Similar charges of federal interference surrounded the 2019 polls in the northern and southern states of Puntland and Jubaland.

Today, Farmaajo’s rivals in Jubaland and Puntland have formed an alliance with a powerful coalition of presidential aspirants and other opposition heavyweights in Mogadishu. They include two former presidents and the speaker of the senate.

As part of the agreement, the election planning was set to commence on November 1.

Members of the opposition, led by former prime minister, Hassan Ali Khaire, warned that extending the president’s term could have negative consequences.

The decision by outgoing president regarding his illegal stay in office is leading to dangerous path.

The current state facing the people in the country will not allow the continued political impasse that resulted in the election delay. The citizens are awaiting their decision, hence the move to extend two years term to plan for ballot elections.

Puntland and Farmajo have two different and conflicting visions of how federalism should and ought to operate in Somalia.Puntland envisions a federal system where the federal states have their own military and even hold their own elections with no oversight from the central federal government. Puntland has its own political and military concerns: confronting Somaliland militarily in the Sool, Sanaag and Cayn regions and the new Daesh threats.

Our case study of March 2020 attests to the fact that the re-election of Jubbaland’s President Ahmed Islam Madobe in summer, 2019 was a major setback for Somalian President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmaajo’s efforts to gain control over Somalia’s federal states and establish a strong central government. Farmaajo thinks that Madobe weakens his position, represents the interests of Kenya (while Farmajo is supported by Ethiopia), breaking the process of Somalia’s integration under the center in Mogadishu.

The federal system of governance was imposed in Somalia through the political calculations of then Ethiopia’s ruling Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and this played conveniently into the hands of political elites in the Garowe province.

While the central government in Mogadishu has the political right and sovereignty to exert its powers all over the country, as all modern states do, it lacks the capacity and means to do so. Farmajo is probably envious of Ethiopia’s Premier Abiy Ahmed’s political blow to the TPLF.

Somalia’s federalism needs urgent reforms and reconstitutions that are unique to the Somalia context.