To maintain stability and prevent further political turbulence, a new Honduras’ government should abstain from pursuing ideologically polarized core projects that could backfire by alienating voters, and focus on strengthening democratic institutions.

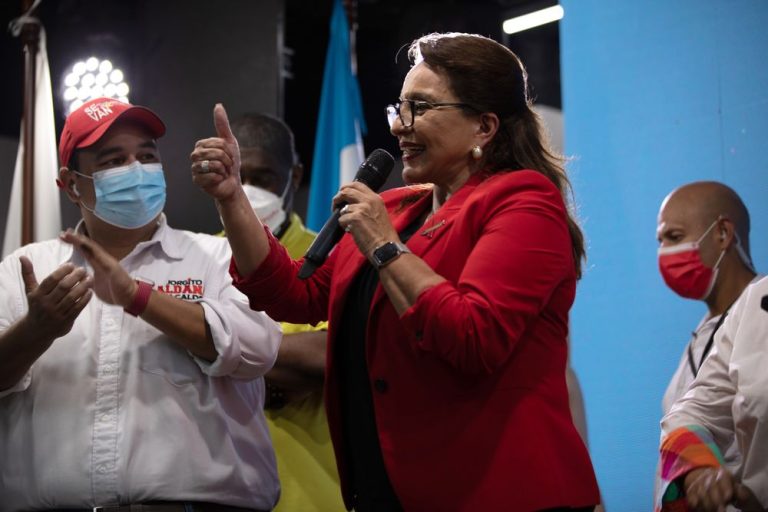

Honduras’ ruling party conceded defeat in presidential elections, giving victory to leftist opposition candidate Iris Xiomara Castro Sarmiento and easing fears of another contested vote and violent protests.

Tegucigalpa Mayor Nasry Asfura, presidential candidate of the National Party, had personally congratulated Castro, despite only about half the voting tallies being counted.

Castro, the wife of former President Manuel Zelaya, the former first lady and representstive of the left-wing Libre Party had 53% of the votes and Asfura 34%, with 52% of the tallies counted, according to the National Electoral Council. It has 30 days from the election to declare a winner. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken congratulated Castro minutes later.

She will face major challenges as the Central American country’s president. Unemployment is above 10%, northern Honduras was devastated by two major hurricanes last year and street gangs drag down the economy with their extortion rackets and violence, driving migration to the United States.

Castro’s government could present challenges, but also opportunities for the Biden administration. Castro herself could remember the U.S. government’s initial sluggishness in calling the ouster of Castro’s husband Manuel Zelaya from the presidency in 2009 a coup, and then proceeding to work closely with the National Party presidents who followed. However, Washington remembers how Castro and Zelaya cozied up to then-Venezuela President Hugo Chávez.So, it is likely, that she will govern as a centrist with a desire to lift up Honduras’ poor while attracting foreign investment.

Manuel Zelaya could make attempts to be the real power behind the throne. Zelaya, whose views are further to the left of Castro, remains a polarizing figure. Being more moderate than her husband, Castro might face a tough choice. But splitting with her own spouse, the undisputed leader of LIBRE, poses high risks.

Before elections Castro said she was ready to form a government of “reconciliation,” and to strengthen direct democracy with referendums.

However, Castro’s ability to govern could be hampered by the outgoing National Party, which has already shown that it will not retreat quietly into the opposition. In 2014, PN lawmakers and allies in the Liberal Party passed a series of late-hour decrees and laws before LIBRE and opposition leader Salvador Nasralla’s deputies took office. The process, known as the “legislative hemorrhage,” sought to maintain privileges for both parties and locked crucial funds. The PN and its allies could try a similar trick to protect themselves from ceding power entirely.

The Castro’s administration will have no time for a honeymoon because of the pandemic, growing fiscal debt, limited state capacity, and widespread poverty. At the same time. Castro can expect little cooperation from the PN-led opposition.

The alliance between LIBRE and Salvador Nasralla, which proved critical to Castro’s victory, is actually quite fragile. Castro and Nasralla have been friends and foes in the past. In 2013, they rivaled each other in the presidential election and split the opposition vote. Nasralla backed Castro weeks before the election, but the road to their successful coalition was full of controversies. Nasralla openly accused Zelaya of murder, and Zelaya responded by saying that Nasralla had “surrendered to the U.S.” after the 2017 election.

Castro’s government program has a worrying and ambitious foundational objective: to summon a Constitutional Assembly. The process will likely increase uncertainty in a country that urgently needs stability and has a recent record of dealing with such issues using extra-constitutional means. In 2009, elites ousted Zelaya when he tried to hold a non-binding referendum to write a new constitution. So, Castro could met the same challenges.

between Castro and the U.S. government common ground exists in at least three areas:

- immigration,

- drug trafficking and

- corruption.

In the first 100 days, Castro will execute and propose to the administration of President Joe Biden a plan to combat and address the true causes of migration.

Castro is a candidate who promised to cut ties with Taiwan in favor of China has been declared the victor in the Honduran presidential elections. One of Castro’s campaign pledges was that if elected, “Honduras will immediately open diplomatic and commercial connections with mainland China.

Honduras, one of Taiwan’s 15 remaining diplomatic allies, has had relations with the country for 80 years. However, this relationship may soon come to an end as a pro-China candidate has emerged as the clear victor in the presidential race.So, the vote also has prompted diplomatic jostling between Beijing and Washington after Castro said she would open diplomatic relations with China, de-emphasizing ties with U.S.-backed Taiwan.

The main risk for stability in post-election Honfuras that incumbent President Juan Orlando Hernández unlikely will leave office quietly, because he and other high-ranking PN officials have been accused of benefiting from drug trafficking dealings, and the Southern District of New York (SDNY). Following Castro’s victory, it’s possible the SDNY may indict Hernández on drug trafficking charges and request his extradition. Hernández could seek immunity by taking a guaranteed seat as a former president in the Central American Parliament, but the Honduran Supreme Court can still approve his extradition. For that reason, Hernández might choose to move to Nicaragua. Hernández and Ortega surprisingly agreed to end a long-held diplomatic dispute concerning the Gulf of Fonseca, suggesting that Hernández was trying to mend relations with a potential ally.