Russia takes advantage of unrest in Kazakhstan to set up a puppet government there and deploy its own soldiers in the country.

The unrest started in the west where mainly oil and gas workers live with their families, as they reacted vehemently to the spike in gas price. Aside from that, most cars are gas-, not gasoline, operated in the western regions, with more financial pressure on household spending. Closed border with China, where most of Kazakh imports came from, and summer drought that hit agriculture have added fuel to the fire.

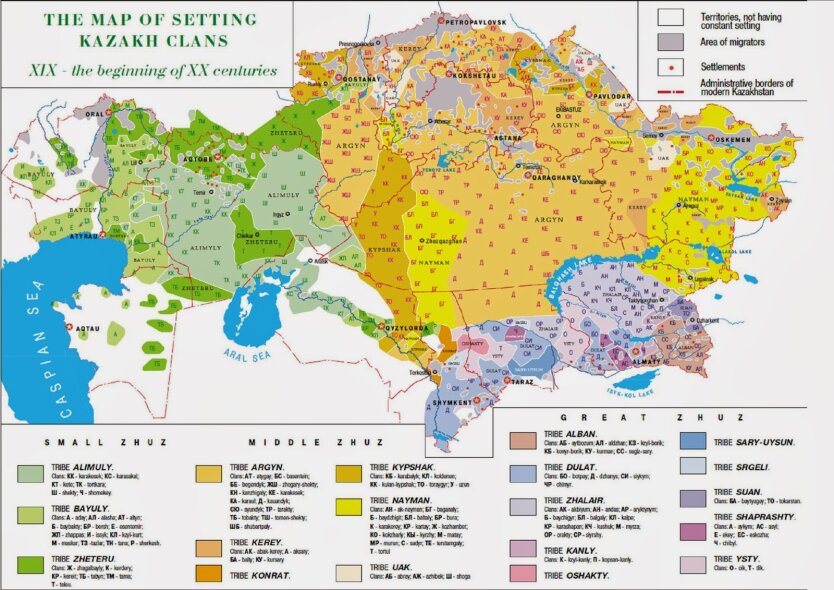

The west of Kazakhstan is home to mostly Junior Zhuz (social category). The Senior Zhuz rules the country, as the Junior Zhuz works. Junior Zhuz leaders, therefore, believe it is not fair that natural resources are located where they live, but managed by people from Almaty (Senior Zhuz).

The Nazarbayev’s clan – Shaprashty, a genus of the Uysun Union of the Senior Zhuz (south and southeast of the country) and his relatives in direct descent, following Nazarbayev’s resignation as the president, maintained hold on power in Kazakhstan’s security agencies. But two daughters of Nazarbayev were from two opposing clans, and their confrontation has finally put Nazarbayev on the back foot.

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev is also from the Senior Zhuz, but from another tribe – the Zhalayyr (Kushik clan). It is not high-profile among the Kazakh clans. Russia, therefore, could have played on Tokayev’s mentality and suggest him an option to expand influence in the country in return for removing the Nazarbayev’s clan and reshaping the government in Kazakhstan.

Unrest in Kazakhstan has spurred the government to resign, and Nursultan Nazarbayev stepped down as the Security Council head. President Tokayev turned to Russia for help, just as Ukrainian President Yanukovych did in 2014. Moscow sent FSB riot control experts to Kazakhstan.

Things seem to be going from bad to worse for Kazakhstan, as there are no opposition and protest leaders there. That facilitates crowd behavior management, guided by the instincts and crowd psychology, rather than on-the-spot centralized instructions. Psyops on social media are active through the channels affiliated with Russia’s Defense Ministry GRU. They play to the tensions between the zhus, families and clans, as they fuel the crowd and direct it at specific targets. However, Russian riot control advisers use old-school approach to deal with unrest, – external influence. Within the given scenario, that will result in more casualties.

On top of it, the law enforcement agencies feature the Naimans, for the most part, who are frosty about the Senior Zhuz. That is why the police have switched sides to join the protesters all around, as Tokayev was ready to seek help from the CSTO. Credibility gap by Tokayev for the army and police promotes influence by Russian soldiers operating under the CSTO flag.

With internal cause of tension in Kazakhstan, the Kremlin has taken advantage of the situation to strengthen Russia’s hand in there.

Odds are good the Kremlin views Kazakhstan as a constituent part of the union that should look like the Soviet Union. President Lukashenko of Belarus has already announced plans to restore the Soviet Union. Kazakhstan is suitable for that, as it, together with Russia and Belarus, is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union – a geopolitical project by the Kremlin. That international project features synchronized economic settlings, as well as legislation, with the military system integrated into Russia-managed CSTO structure.

Armenia is likely to be the next one to join the renewed analogue of the Soviet Union, with so-called Russian peacekeepers deployed in Nagorno-Karabakh, following Yerevan’s defeat against Azerbaijan in the war of 2021. The Kremlin understands that Armenia’s dependence on Russia will keep growing, with odds high for Yerevan to be persuaded to take part in Moscow’s geopolitical project.

A lightning-fast respond by the Russian parliament, just a day after Russian soldiers had been sent into Kazakhstan, that suggested a referendum to reunify with Russia, and permanent deployment of CSTO peacekeepers (that is, Russia) in Kazakhstan, speaks for the fact that Russia has initially planned an operation in Kazakhstan. That is also confirmed by the fact that Russian soldiers in Kazakhstan operate under General Andrey Serdyukov’s command, the one responsible for the operation to annex Crimea (Ukraine) in 2014. Russian soldiers perform just like in Crimea: take control of the airport, deploy Russia’s special operations forces (Senezh, Kubinka-2) and landing forces, set up checkpoints to enter populated areas.

Since the outbreak of Russian aggression against Ukraine, lots of analysts have claimed the same scenario was likely to recur in Northern Kazakhstan, as it shares borders with Russia, and mostly ethnic Russians live there. The operation launch in Kazakhstan has also got common features with the pattern in Ukraine of 2014:

1. Civil unrest in the country.

2. Rise in national identity (the ex-President Nazarbayev’s clan promoted the idea of changing the Cyrillic alphabet for the Latin one. Nazarbayev emphasized the Kazakhs’ priority, discredited Moscow’s role in Soviet times, irritating the Kremlin that harks back to the Soviet Union.

3. Rhetoric by President Putin that Kazakhstan is an artificial state formation, and the Kremlin denies this country is a state.

At the same time, the developments show the Kremlin has gone beyond the plan for an operation in Northern Kazakhstan and is targeting to gain control over the whole Kazakhstan.

In June 2020, Tokayev denied the intention by Kazakhstan to join the union state. But just like with Belarus, Moscow is realigning the developments with bloody fight against the rioters, mug-slinging against the countries’ leaders, fencing them off from the rest of the world, as it monopolizes their external contacts.

Starting from fall of 2021, Tokayev’s narrative on the Russian language and the Russian community in Kazakhstan (18.5% of the population) has been in stark contrast to the one of the Nazarbayev years and became not just softer, but even quiet, Moscow-friendly. Tokayev, unlike his predecessor, is not so keen on the Kazakhs’ national identity, he is surrounded by Kremlin-friendly people.

It is clear that Moscow chose Tokayev to represent its interests in Kazakhstan, as it backs him up in return for the Russian language support. Odds are good Kazakhstan, under pressure from the Kremlin, will agree to recognize Crimea as Russia’s territory, restore the Russian language as the second official language in Kazakhstan and allocate Russian military facilities there. That is due to the limited length of stay by the CSTO-sponsored troops, as Russia has started to use it to get its own political things done and cover up for its role in managing and staging.