The trial against the former leaders of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), Hashim Thaçi- former commander-in-chief of KLA and the other KLA heads, Kadri Veseli, Jakup Krasniqi and Rexhep Selimi started on Monday, April 3, after more than two years from the confirmation of the indictment. On the first day of the trial, the course of the indictment took an unknown path for most.

Thaci served as president of Kosovo from 2016 until his resignation in 2020 following his indictment.

Read also: The Shadows of a Court

Veseli and Krasniqi served as a former chairman of the Kosovo assembly while former Member of Parliament Selimi was a founding member of Thaci’s Democratic Party of Kosovo, PDK.

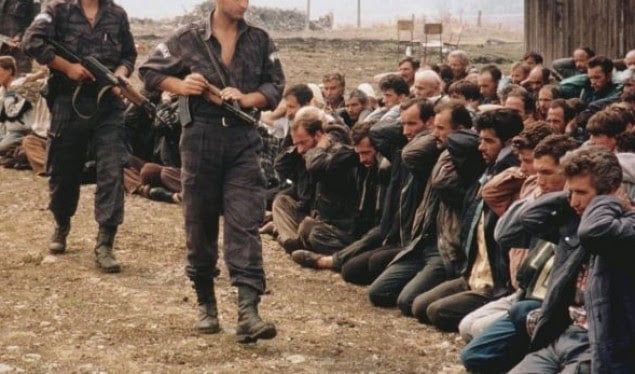

The four are charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes that took place during the 1998-1999 armed conflict against Serbian forces in Kosovo.

They have been accused of persecution, imprisonment, illegal or arbitrary arrest and detention, other inhuman acts, cruel treatment, torture, murder, and enforced disappearance of persons.

When the Specialized Chambers of Kosovo, based in The Hague, opened the indictment against the four former leaders of the KLA, they did it respectively not against individuals for crimes directly related to each of them, but against the General Headquarter of the KLA, which from the Office of the Specialized Prosecutor was equated with a “joint criminal enterprise”.

Despite the efforts of the Specialized Prosecutor’s Office to say that this process is against individuals and not against KLA, it is denied on the 35th point of the indictment – which portrays almost all political leaders as members of “a joint criminal enterprise” and the KLA soldiers.

By participating in a joint criminal enterprise, the accused wanted control over “all of Kosovo by means including unlawfully intimidating, mistreating, committing violence against and removing those deemed to be opponents”, the prosecutor said.

Such opponents included “alleged suspected collaborators with Serbian forces, as well as officials, state institutions and those who did not support the aims of the KLA, including associates of the Democratic League of Kosovo, Serbs, Roma and other ethnicities”.

The Office of the Specialized Prosecutor has said that at the time covered by the indictment, in Kosovo and the north of Albania there were more than 40 detention centers, where more than 400 people were illegally detained. At least 102 had been killed and more than 20 others are considered missing.

The Special Prosecution in the 5-hour speech to present the case against Hashim Thaçi, Kadri Veseli, Rexhep Selimi and Jakup Krasniqi, tried to argue that the Kosovo Liberation Army was a well-organized structure with a clear hierarchy of action.

Consequently, according to the court, the crimes committed during the war and shortly after the war took place on the order of the KLA and the general headquarter respectively.

The first charge against Thaci and others is that “through the actions and omissions of Thaci and others through their participation in a joint criminal enterprise , they committed or aided and abetted the crimes presented in this charge”.

Also, according to the prosecution, “Thaçi and others are responsible as superiors for crimes committed by their subordinates”.

The prosecution said that “Thaci and others knew or had reason to know that the crimes presented in this indictment were about to be committed or were committed by their subordinates, but they did not take the necessary measures to prevent those crimes.”

Some of the problems related to the special court

The first problem has to do with which law the special court is applying. Perhaps knowing that with accusations of direct crimes the case would not have been solid, the prosecution adapts the line of “joint criminal enterprise”, because it is an extended form of responsibility.

It should always be taken into account that the Specialized Chambers were created as a court of Kosovo, and not an international court, with headquarters in The Hague. They should be within the system of the Republic of Kosovo. But for the reasons we explain below, they are based outside the Republic of Kosovo and with foreign prosecutors.

The Constitutional Court of Kosovo gives this definition for its existence “The Court considers that the specialized court, as foreseen by this provision, means a court with a specified scope of jurisdiction that remains within the existing framework of the judicial system of the Republic of Kosovo and that acts in accordance with the principles of that system”.

What is actually happening is that the special court is applying a different substantive law regarding the charge of “joint criminal enterprise”. To make the latter possible, customary international law is being applied, contrary to the laws and the Constitution of Kosovo.

Normally, the accused would have to be judged according to the law that was in force at the time when the crimes included in the accusation were committed, and in this case we are talking about the criminal code of the former Yugoslavia of 1976. But this law, in the form of liability does not include joint criminal enterprise.

Neither the Kosovo constitution nor the law on specialized chambers provides for the application of joint criminal enterprise.

Virtually all trials for war crimes in Kosovo conducted by the local court, EULEX and UNMIK have been and continue to be based on the criminal code of the former Yugoslavia.

The second problem has to do with hidden evidence.

Dastid Pallaska, part of the defense team of the former president Hashim Thaçi, has said that the Special Prosecutor’s Office for four years, since 2018, has hidden the testimony of the former OSCE ambassador to Kosovo, Dan Everts.

“This testimony was revealed only when the prosecution was caught hiding the evidence, namely during the investigations by the defense and only after the prosecution realized that we have discovered the existence of the evidence”, continued Pallaska.

Similarly, the letter of the US Department of State dated May 4, 1999, which states that there was no political structure or efficient command and control of the KLA, has never been exposed.

“Furthermore, since there is no political structure in Kosovo or effective command and control of the KLA it would take many months, if not years, to organize them to use and maintain any military assistance that the United States would provide.” offer you“, the letter said.

Read also: Parallaxes of anecdotical justice

A CIA report has also been hidden, where in one paragraph it is quoted that “the KLA was not involved in terrorist activities – defined as premeditated, politically motivated violence, carried out against civilian targets”.

It is also curious the amount of time required by the special prosecutor to present the case against Thaçi and others of 1863 hours or 10 years, when for the crimes committed by Slobodan Milosevic in several countries in a span of 9 years, 360 hours were required to submitted evidence, or 2 years.

The third problem, but which is probably the main one, has to do with the mandate of the Court.

This court was established based on Resolution 1782 of 2011 of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, according to a report by former Swiss prosecutor Dick Marty.

The 2011 report by Dick Marty, then member and rapporteur of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe raises allegations of inhumane treatment of persons and illegal trafficking of human organs allegedly committed by members and KLA leaders, precisely from the “Drenice Group” headed by Hashim Thaci, for which international investigators failed to find evidence and facts.

So the claims of Marty’s report remain unsubstantiated and unproven.

As it would later turn out, most of Marty’s report was documentation prepared by Serbian institutions.

The former Serbian ambassador to Switzerland, Milan Protic, would later tell how they met with Marty to hand over the documents to him.

Narrated in his book “In the birthplace of William Tell: History from Switzerland”, Protic also described details of the meeting.

“We were waiting for Dick Marty in an alcove in the Banhof in Zurich. In place of the impressive figure of Sean Connery appeared the unconvincing appearance of Dick Marty. Finally, the show could start”, wrote Protič.

Later, Protic, together with the Serbian prosecutor for war crimes Vladimir Vukcevic, had convinced the Swiss senator to accept their files.

How the Special Court of Kosovo was born

After the Resolution of the Council of Europe based on Dick Marty’s report, the USA and the EU agreed on the creation of a special court under the legal umbrella of Kosovo, but with foreign lawyers and located in The Hague.

Russia, Serbia as well as some other countries requested a special court under the UN and not under Kosovo.

The compromise supported by the USA was found precisely in its placement in The Hague with foreign judges and prosecutors, so that the witnesses felt protected in relation to the trial, but within the judicial framework of Kosovo.

The Assembly of Kosovo failed several times in approving the law for the establishment of this court. This is also due to opposition from Albin Kurti’s Vetevendosja (Autodetermination) party, the largest opposition in the country.

The law it is approved in August 2015, after a public and direct pressure from the USA.

Two years later in 2017, 43 Kosovo MPs would request the abolition of the Special Court. This was even after it was realized that none of Marty’s accusations were proven and Kosovo’s Specialized Chambers were demanding an investigation into alleged crimes by KLA members against ethnic minorities and political rivals, allegedly committed since January 1998 until December 2000.

The reaction of the Trump administration was not different from that of Obama. The United States and the European Union were determined to support the activity of the Special Chambers.

The request for the annulment of the court remained in circulation until the end of 2019.

This scenario happens alongside another.

The friction between the American administration of President Trump and the EU, or better Germany and the United Kingdom, regarding the possibility of exchanging territories between Serbia and Kosovo as an opportunity for the normalization of relations between the two countries.

Then, when it became clear that the president of Kosovo, Hashim Thaci, was in favor of the possibility of territorial changes supported by the American administration, the EU would immediately react in opposition.

The end of 2018 and 2019 will therefore also see this issue in the center. Discussion of options for territorial changes between Kosovo and Serbia.

Germany clearly expressed concern about a domino effect in other Balkan countries, and Great Britain and other countries also expressed concern about the effect it could have regarding the situation in Ukraine after the annexation of Crimea by Russia.

Once again, in this situation, the positions of Thaci and Kurti would be opposite. Kurti, not so worried about the consequences but mostly worried about his political future, would line up with Germany regarding territorial changes and border corrections.

Precisely in a situation of cooling and disappointment towards the EU on the part of President Thaci, and when the latter was on the verge of leaving for the USA, most likely for an agreement with Aleksander Vucic on border changes, in June 2020 the prosecutor’s office of the special chambers accused President Thaci and other KLA leaders of war crimes and crimes against humanity, murder, enforced disappearance, persecution and torture.

While it is up to the defense lawyers to be able to show the innocence of the accused and above all to show that unlike the prosecution’s claims, the KLA “never had a vertical chain of command” and was not an army with “hierarchy well-organized and with a functional structure”, the history of the birth and development of this special court clearly shows that the political factor cannot be overlooked, as it lies at the base of the foundations of this court.

Time will tell the result and consequences.

Read also: Kosovo: political or justice decision?

Post Author

Author

-

Researcher on International Relations Middle East and Balkans

View all posts

CSSII- Centro Interdipartimentale di Studi Strategici, Internazionali e Imprenditoriali,

Università di Firenze, Italy, Albania